Sandra Sanchez*

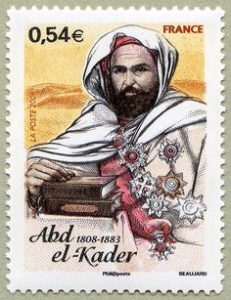

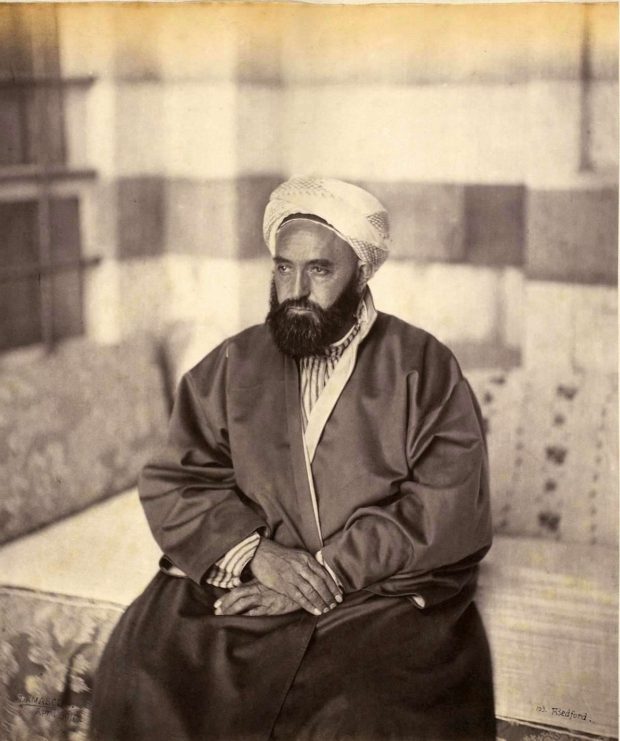

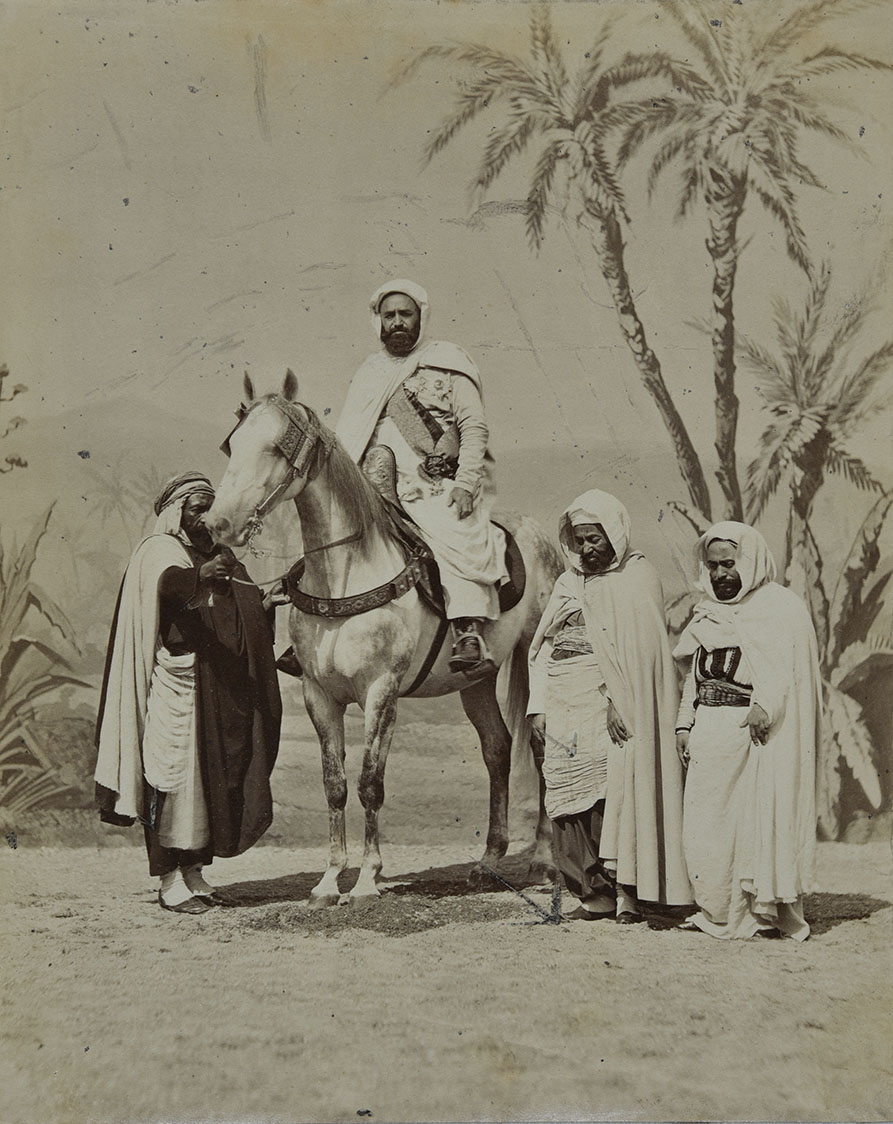

As The New York Times wrote in its obituary, “Abdelkader was one of the ablest rulers and most brilliant captains of this century “[1]. This multifaceted Algerian emir, leader of the resistance against the French occupation and considered the founder of the Algerian nation, was guided throughout his life by Sufism and the teachings of Ibn ˁArabī of Murcia. In addition to his opposition to the French during the invasion of Algeria, he is remembered for his role in protecting the Christian inhabitants of Damascus during the events of 1860.

Emir Abdelkader was born in El Guettana, in the region of Oran, in 1808, into a noble family related to the Prophet Muhammad. He was educated in various modern sciences and acquired a profound knowledge of Islamic sciences due to the environment in which he grew up, in addition to receiving a military education. He also made a pilgrimage to Mecca with his father, and visited Egypt ruled by Muhammad Ali in the midst of modernisation. They also travelled to Damascus, where Abdelkader visited the tomb of Ibn ˁArabī, whom he regarded throughout his life as his spiritual guide. These visits would have a big impact on his future character.

French invasion, 1832-1847

The French Empire invaded Algeria two years after Abdelkader and his father returned to the country. Abdelkader’s father was one of the leaders of the resistance against France. After he fell ill, his position was taken over by his son. Abdelkader rallied the tribes of Oran under his leadership, and it was these same tribes who proclaimed him sultan in 1832. Abdelkader rejected this title as he considered it only applicable to the Sherif of Fez of the Khirifian Empire (now Kingdom of Morocco), and so he adopted the title of Emir[2].

The French Empire invaded Algeria two years after Abdelkader and his father returned to the country. Abdelkader’s father was one of the leaders of the resistance against France. After he fell ill, his position was taken over by his son. Abdelkader rallied the tribes of Oran under his leadership, and it was these same tribes who proclaimed him sultan in 1832. Abdelkader rejected this title as he considered it only applicable to the Sherif of Fez of the Khirifian Empire (now Kingdom of Morocco), and so he adopted the title of Emir[2].

Following the signing of the Treaty of Desmichel in 1834, which recognised the Emir as the independent governor of the Oran region, Abdelkader set about strengthening tribal loyalties and the administrative development of the region. Among other things, he organised the army and various fortifications for the defence of the country, set up education and health systems for the entire population, and provided himself with various channels of information to keep himself up to date. He also employed the Jewish population under his command in trade with France and Britain.

Even if some prisoners wanted to convert to Islam, Abdelkader asked them to reconsider, for in the event of a prisoner exchange, the French converts would be treated as traitors.

In 1839, the French launched another attack, which was considered by the resistance a clear violation of the Treaty of Tafna, signed in 1837. This treaty, signed by the Emir and General Bugeaud, recognised the French authority over the territory, dividing Algeria into two regions: the urban areas for the French, and the rural areas (almost a third of Algeria) for Emir Abdelkader. The latter used the treaty to consolidate his power and establish new towns outside French control. From 1842 onwards, he began to lose several of his possessions and fled to Morocco, where he mediated a break in relations between the Maghreb country and France in 1844. However, shortly afterwards, in 1847, the Emir had no choice but to surrender to General Lamoricière in exchange for permission to live with his family and followers in Palestine. But this did not happen. Instead, they were transferred to the French city of Toulon and to Fort Lamalgue, on the grounds that they needed time to organise their arrival in Alexandria or St John of Acre, where Abdelkader wanted to go into exile. Within a few months, they were sent to another French town, Amboise, where they remained imprisoned until their release in 1852 by Napoleon III, in exchange for their commitment not to rebel against France.

Treatment of prisoners

During the French invasion, Abdelkader established a strict humanitarian code for the treatment of prisoners of war. According to Charles Henry Churchill[3], a British naval officer and consul in Ottoman Syria, the treatment of prisoners by Arab tribesmen improved under the control of Abdelkader. French prisoners were treated well: they were given adequate money, clothing and food, and were provided with whatever spiritual guidance they needed. On one occasion, the bishop of Algeria was asked to send a priest to the camp to take care of any religious matters for the prisoners, such as prayer or ‘whatever they wished or wanted, to alleviate the rigours of their captivity’. The mere presence of a prisoner aroused in Abdelkader ennobling feelings about human nature.

Even if some prisoners wanted to convert to Islam, Abdelkader asked them to reconsider, for in the event of a prisoner exchange, French converts would be treated as traitors. Another prisoner said that he would never renounce his religion, even if he was to be killed, and Abdelkader replied: “Don’t worry, your life is sacred with me”, and praised his bravery.

The mere presence of a prisoner aroused in Abdelkader ennobling feelings about human nature.

Moreover, the Emir was reluctant to make women prisoners, as he was horrified by the idea of them being casualties of war. Thus, Abdelkader’s mother, Leila Zohra, became the guardian of all women prisoners: their tent was set up next to hers, and no one was allowed to approach it without Leila Zohra’s consent. She fed the prisoners herself, and if any of them fell ill, she personally took care of her.

When they could not provide for the subsistence of the captives, Abdelkader would release them. Once, he released and escorted 94 French prisoners to his compatriots, without asking for anything in exchange, only because he could not provide for their sustenance. He also had a number of French craftsmen working for him, and protected them from rival tribes when war broke out. He offered them escorts and paid them all the money agreed upon for their services, even if they had not finished the work.

He also established a national edict to prevent the mistreatment of French prisoners, as isolated cases continued to occur despite his strict vigilance. With the edict, he made any owner of a French or Christian prisoner responsible for his proper treatment and for handing him over to an authority in exchange for a reward. If the prisoner had any complaints about his captor, he would not receive the promised money.

Likewise, barbarity against prisoners was severely punished, even with dead enemies. He defined the mutilation of corpses as “cowardly and brutal”, in accordance with Islamic morality, and those who committed such an act were punished.

It is worth noting that during Abdelkader’s exile at Fort Lamalgue in Pau, the Emir received numerous visits from French social figures and even prisoners of war who had been captured during the invasion of the country[4].

Exile

After a hard time in Amboise, where his living conditions were very precarious, Napoleon III released Abdelkader and allowed him to settle in the city of Bursa, in present-day Turkey, with a generous pension and the promise that Abdelkader would never again resist France.

Soon after, Abdelkader and his family moved permanently to Damascus. He only left the city for specific trips, such as the pilgrimage to Mecca and the visit to the Paris Universal Exposition of 1867. The choice of Damascus as his habitual residence was not random, as it is there that Ibn ˁArabī is buried. The first thing that Abdelkader did upon his arrival in the city was to visit the tomb, and then he took up residence in the house where the Andalusian had lived. From then on, he devoted himself exclusively to his family, study and teaching at the Great Mosque of Damascus.

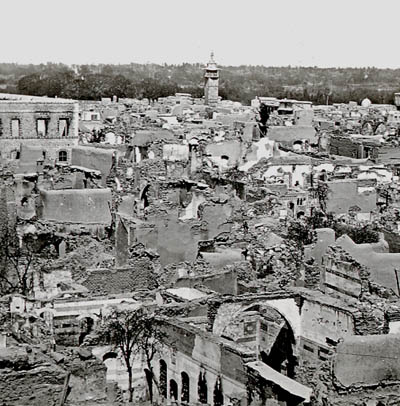

The Damascus events of 1860

While Abdelkader was living in Damascus, clashes between the Druze and the Maronite population led to massacres targeting Christians living in the city[5]. These clashes resulted in thousands of Christian deaths, but Abdelkader managed to rescue approximately 15,000, according to Churchill’s figures.

The situation in Damascus was already tense in the summer of 1860, and during the month of June there were numerous clashes between Christians and Druze in the villages near the city. The arrival of these Christians in Damascus in large numbers may have been an incentive for what was to happen during the following month. The Ottoman governor, however, was not very concerned about the situation.

The turning point was the capture of Zahlih, a town near Damascus, by the Druze in mid-June. The misbehaviour of the Christians in Zahlih towards the Muslims caused the latter to welcome the news with great joy. The government also indirectly welcomed the Druze action. Abdelkader urged Ahmad Pasha, the then Ottoman governor, to offer protection to the Christians from the Muslim attacks they were suffering, since killing Christians is forbidden by Islamic law[6]. Still, any action taken by Ahmad Pasha increased the feeling of insecurity among Christians and Muslims alike[7].

Wealthy families, such as those of the European consuls, continued to reside with Abdelkader for some time until they were finally escorted to Beirut.

However, Abdelkader’s followers were provided with weapons, which would not be used until the revolt, when he stopped an angry mob marching towards the Christian quarter. Although his speech had no effect and the attackers entered the neighbourhood, Abdelkader and the rest of the Algerians managed to rescue and shelter a big number of Christian families, which they then escorted in many and numerous groups to the Turkish authorities. However, he still had to protect them from Turkish plots on several occasions.

Wealthy families, such as those of the European consuls, continued to reside with Abdelkader for some more time, until they were finally escorted to Beirut.

The Turkish authorities acknowledged the humanity of Abdelkader’s intervention, but asked him to surrender his weapons, which he flatly refused. The Christian powers, for their part, showered Abdelkader with enormous expressions of gratitude and admiration. Decorations and gifts were accompanied by letters of thanks from France, the United Kingdom and the Ottoman Empire. Praise also came from different parts of the Muslim world, including a letter from Imam Shamil, the Hero of the Caucasus, who noted his sadness at the misconduct of Muslims and his admiration for the actions of Abdelkader[8].

The legacy of Abdelkader

In addition to his military achievements, Abdelkader was a great writer and left behind a wide range of written works after his death, of which his poetry and his work Kitab al-mawaqif, devoted to Sufism, are particularly noteworthy. His work as the first modern editor of Ibn ˁArabī’s works is also important.

As mentioned, notable among the Emir’s literary works is his Kitab al-mawaqif, or ‘Book of Stops’, a Sufi discourse, a mixture of prose and poetry, on Ibn ˁArabī’s teachings[9]. The themes of the Emir’s poetry, mostly written during his exile in Amboise, revolve around Bedouin life. His poems yearn for the desert and the wandering life, as shown in the title of one of his poems: ‘There are no defects in the nomadic life’ or, as it has been translated, ‘In Praise of Bedouin Life’, ‘The Desert’ or ‘The Desert Life’. His poems are true exaltations of the Bedouin condition and all its characteristics, including lessons from this way of life[10]. Also important is his mystical poetry, to which, as a Sufi Muslim, he dedicated several works. In his poems, Abdelkader shows himself to be closely linked to the teachings of Ibn ˁArabī, and several appear in the introduction to the Kitab al-mawaqif[11].

In addition to his military achievements Abdelkader was a great writer and after his death he left behind a wide range of written works, of which his poetry and his work Kitab al-mawaqif, dedicated to Sufism, are particularly noteworthy.

Abdelkader died in Damascus in 1883 at the age of 75. He was buried next to Ibn ˁArabī, and, when Algeria finally gained independence from France, he was moved to a section of the El Alia cemetery dedicated to the martyrs of the Algerian resistance. He was buried between Larbi Ben M’hidi and Mourad Didouche, two leaders of the National Liberation Front[12], the 20th century Algerian political party that led Algeria’s independence.

The figure of the emir can be considered the most important figure in 19th century Algerian history[13]. Kateb Yacine and his book ‘Abd al-Qadir and Algerian Independence, described him as “an Algerian national hero and leader of the ‘war of independence'”. His figure was also claimed by the nationalists of the time to fight for the liberation of the country, although their demands did not become visible and important until after the Second World War. It was then that Abdelkader became a true martyr of the Algerian resistance and a myth that united the national population against French imperialism.

* Article written as part of the internship agreement signed between the Islamic Culture Foundation and the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, in the Degree in Asian and African Studies.

References

[1] OBITUARY.; ABD-EL-KADER. (12/11/1873). The New York Times. [https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1873/11/12/79055138.html]

[2] Mahmoud-Makki Hornedo, L. C. (2012). ˁAbd al-Qādir al-Ŷazāˀirī, líder de la resistencia argelina, poeta y místico. Al-Andalus Magreb, 19, 309-344. Recuperado a partir de https://revistas.uca.es/index.php/aam/article/view/7250

[3] Churchill, C.H. (1867). Life of Abd el-Kader: Ex-Sultan of the Arabs of Algeria. Chapman and Hall, Londres.

[4] Étienne B. (1994). Abdelkader. Hachette, París.

[5] Abu-Mounes, R. (2022). «Chapter 6 The Notables of Damascus and the 1860 Riot». En Muslim–Christian Relations in Damascus amid the 1860 Riot. Leiden, Brill. [https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004470422_008]

[6] Abu-Mounes, R. (2022). «Chapter 4 The 1860 Riot in Damascus». En Muslim–Christian Relations in Damascus amid the 1860 Riot. Leiden, Brill. [https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004470422_006]

[7] Ibid.

[8] Churchill, C.H. (1867). Life of Abd el-Kader: Ex-Sultan of the Arabs of Algeria. Chapman and Hall, Londres.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jansen, J.C. (2016). Creating National Heroes: Colonial Rule, Anticolonial Politics and Conflicting Memories of Emir ‘Abd al-Qadir in Algeria, 1900–1960s. History and Memory, 28(2), 3-46. [https://doi.org/10.2979/histmemo.28.2.0003]

[13] Ibid.

No Comments