The Convivencia in question

Convivencia: Spanish noun, from convivir, to live with the other, used by historians in the 20th century to describe inter-religious coexistence in al-Andalus, between the 8th and 15th centuries. The roots of this word, and of its Occitan twin Convivencia, lie in an ancient Pyrenean matrimonial alliance [1]. In the 8th century, Llívia, a small Pyrenean town in Cerdagne, welcomed an Amazigh/Berber-Occitan couple. He was killed, she was exiled, the marriage ended badly. But this union, later magnified by the romantics, continues to nourish the concept of Convivencia, a concept with strong political potential. A story of halted territorial expansion, a pact between dissidents, an “unnatural” marriage and, ultimately, the re-establishment of the warrior order.

Convivencia is part of the history of the Occitan Mediterranean region, which saw the peaceful cohabitation of Sephardic Jews from Spain, Muslims (Arabo-Andalusians) occupying Septimania (today’s Languedoc Roussillon) and Provence, and the Visigoths building Toulouse (Tolosa). This small world traded skilfully, Narbonne shone as brightly as Byzantium, and marriages between communities strengthened alliances [2]. Occitanie is a land of historic welcome. It has integrated and helped many peoples, tolerated or assimilated many different origins. A singular state of mind that took as its model, in the 8th-10th centuries, Arab-Berber Andalusia, also known as al-Andalus. From the 12th century onwards, Occitan society, known as the “troubadour society”, in turn produced civilizational concepts of equity. The term “Paratge“, expressing the (relative) principle of equality between the sexes and social classes, appeared. For the first time, it was not aristocratic lineage that prevailed, nor force or violence, but culture.

Convivencia refers to the period of Spanish history from the Muslim conquest of Spain in the early 8th century until the expulsion of the Jews in 1492.

This spirit, which permeated the whole of society, including some of the working classes, was unfortunately called into question when the Crusade against the Albigensians (1209-1229) began. Its late rediscovery only came in the 20th century. The Surrealist poets of the inter-war years, along with a number of leading figures in the French intelligentsia, such as Simone Weil, sang its praises. In her Cahiers [3], for example, the philosopher compared the Chanson de la Croisade contre les Albigeois to Homer’s Iliad.

Convivencia [4] refers to the period of Spanish history from the Muslim conquest of Spain in the early 8th century until the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. This era is characterized by the relatively peaceful coexistence of Muslims, Christians, and Jews in the Iberian Peninsula.

Here are some key points about this period:

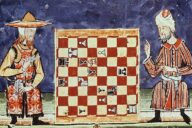

- Cultural Exchange: The Convivencia led to significant cultural, scientific, and intellectual exchange among the three religious communities. This included advancements in fields such as medicine, astronomy, philosophy, and literature.

- Economic Collaboration: Muslims, Christians, and Jews often worked together in trade, commerce, and craftsmanship. Cities like Córdoba, Toledo, and Granada became thriving centers of economic activity.

- Religious Tolerance: Although there were instances of conflict and tension, there were also periods of religious tolerance. Non-Muslims (dhimmîs) [5] in Muslim-ruled territories were allowed to practice their religion and maintain their own legal systems in exchange for paying a tax (jizyah) [6].

- Architectural Achievements: The era saw the construction of many iconic buildings, such as the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the Alhambra in Granada, and the synagogue of El Transito in Toledo, which reflect the diverse cultural influences of the time.

- Decline of Convivencia: The Convivencia began to decline with the Reconquista, the Christian reconquest of Spain, which culminated in the fall of Granada in 1492. The establishment of the Spanish Inquisition and the subsequent expulsion of Jews and Muslims marked the end of this period of relative coexistence.

- The legacy of the Convivencia continues to be a subject of historical study and debate, highlighting both the potential for intercultural harmony and the challenges of religious and cultural integration [7].

Raquel Sanz Barrio writes on the concept of conviviality between three religions and cultures in Spain [8]:

“In the Middle Ages, the Iberian Peninsula witnessed the simultaneous presence of three religions, in other words, three cultures. These religions, all originating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, had many features in common. The Muslims, who expanded their territory spectacularly across the whole of North Africa, reached Iberia in the middle of the 8th century. In just a few years, they had dominated most of the peninsula. The Jews, for their part, had already been present since Roman times, and the persecution they suffered in the last decades of the Visigothic monarchy drove them to side with the Muslims. Jewish communities flourished in al-Andalus until at least the end of the 10th century. Christian Spain also welcomed Jews with open arms, as demonstrated by the reign of the Castilian-Aragonese monarch Alfonso VI, to whom we owe the famous Carta inter Christianos et Judeos, dated 1090, almost contemporaneous with the first great wave of anti-Judaism in Europe following the call for the Crusade. Each of the three great religions attributed a specific name to Iberian soil. Christians called it “Hispania”, Muslims “al-Andalus” and Jews “Sefarad””.

Introducing Convivencia?

Al-Andalus, Spain under Muslim rule, brought together Muslim conquerors, Hispanic Christians and a Jewish community present since antiquity. Christians and Jews had a dhimmî status, but the Umayyad period (756-1031) is said to have been a “golden age” of harmonious cohabitation that encouraged the Muslim, Christian and Jewish communities to flourish: Convivencia [9]. Convivencia, a Spanish term meaning “coexistence,” refers to a historical period in the Iberian Peninsula, primarily in al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), from the 8th to the 15th centuries. This era was characterized by the coexistence of different religious and cultural groups, including Muslims, Christians, and Jews. This coexistence fostered significant cultural exchange and intellectual advancement. However, it’s important to remember that this “coexistence” wasn’t always peaceful and harmonious, as tensions and conflicts did exist [10]. Convivencia [11] (Spanish, from convivir, “to live together”) is a concept that was used by historians of Spain in the 20th century, but was much debated as anachronistic, then abandoned by most in the 21st century, to evoke a period in the medieval history of the Iberian Peninsula (and al-Andalus in particular) during which Muslims, Jews and Christians coexisted in a state of relative confessional peace and religious tolerance, and during which cultural exchanges were numerous [12].

According to Américo Castro, the three cultures coexisted harmoniously, while at the same time a process of acculturation and integration of the minorities took place.

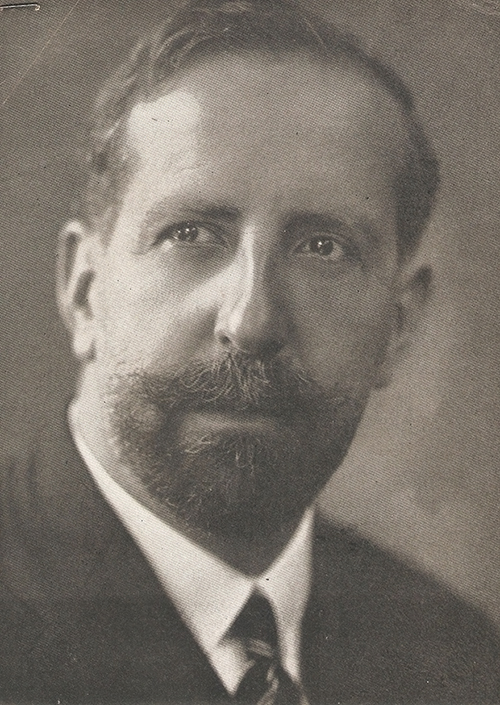

This concept was first put forward by Américo Castro [13] to describe relations between Christians, Jews and Muslims in the peninsula during the historic Hispanic period, from the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 to the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in the crucial year 1492 after the end of the Reconquista [14]. Castro presents this period as one of “stabilized pluralism“, in which exchanges and dialogues enriched groups of different obedience, with essentially peaceful relations, and asserts that it is this conjunction that favors the cultural development of the peninsula [15].

In his book Spain in its history: Christians, Moors and Jews (1948) (España en su historia: cristianos, moros y judíos (1948)), Américo Castro characterized the relations of the three groups during the Middle Ages as “a good coexistence“. According to the famous historian, the three cultures coexisted harmoniously, while at the same time a process of acculturation and integration of the minorities took place [16]. Américo Castro’s book drew attention to the plural nature of Spanish identity and to the contributions of Arabs and Jews in the creation of peninsular culture [17]. More recently, other historians have argued that relations between the three groups were not as idyllic as Castro presented them and that along with periods of concord, there were also moments of great social conflict [18].

Because the interaction of these three groups developed over 8 centuries and in very different circumstances–moments of splendor of the Arab civilization and precariousness of the Christians and vice versa; social prestige of the Jews and occasions of anti-Semitism, etc–it is very difficult to affirm or totally deny the “culture of tolerance.” What does seem to be unanimously accepted is that in art, literature, music, etc., the relations between the three civilizations were very fruitful and gave rise to unique creations. An important example is Mudejar art [19], which applies elements and techniques from Islamic art to Christian and Jewish buildings, such as churches and synagogues.

Kenneth Baxter Wolf introduces Convivencia in the following terms [20]:

“Convivencia refers to the ‘coexistence’ of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish communities in medieval Spain and by extension the cultural interaction and exchange fostered by such proximity. The term first appeared as part of a controversial thesis about Spanish historical identity advanced by Américo Castro in 1948. Since then interest in the idea of convivencia has spread, fueled in part by increased attention to multi-culturalism and rising concern about religiously framed acts of violence. The application of social scientific models has gone a long way toward clarifying the mechanisms of acculturation at work in medieval Spain and tempering the tendency to romanticize convivencia.”

Following in the footsteps of Spanish historian Américo Castro, the concept of Convivencia will continue to spread in Spain, Catalonia and Occitania. Intellectuals and associative cultural leaders have been busy refining, reinterpreting and adapting it, to the point of proposing it as the basis for a new social refoundation. In its 1992 Diccionario de la lengua española, the Real Academia española gave a minimal definition of Convivencia, namely “accion de vivir en compañia de otro u otros, cohabitar“. In its Diccionario del uso del español of the same year, Maria Moliner specifies “hecho de vivir en buena armonia buena armonia unas personas con otras” (living in harmony with one another) [21].

In 2011, the Fondacion Occitània will provide decisive elements: “un biais de viure amassa dins lo respièch de l’alteritat -en se e fòra seen tota egalitat“, or “an art of living together with respect for otherness -in and beyond – in complete equality”. First realized, more or less harmoniously, within the framework of the 10th century Caliphate, Convivencia was taken up by the Muslim kingdoms of the 12th and 13th centuries, in Toledo and Saragossa. The Troubadours civilization, closely linked to the Convivencia drew its inspiration from these kingdoms and gave it the name Paratge. Among the many concepts developed by the Troubadours (Fin’amor, Prètz, Jòi, Mezura, Cortesia, eca…), Paratge is one of the most encompassing. Repeated some fifty times in the Cançò (13th century), it bears witness of an entire civilization where nobility of heart and mind prevails over that of lineage. The terror of the Crusades and the Inquisition would soon put an end to this humanist experiment. In the 20th and 21st centuries, researchers, writers and cultural organizers revisited the concept, and Paratge became the medieval basis for contemporary Occitan Convivencia.

Paratge, writes Fernand Niel, means [22]:

“Honor, righteousness, equality, denial of the right of the strongest, respect for the human person, for oneself and for others. The paratge applies to all domains, political, religious and sentimental. It is not to a nation or a social category, but to all men, whatever their condition or ideas”.

Religious cohabitation

But while religious cohabitation was the norm on the medieval Iberian Peninsula, the concept of Convivencia, in its academic sense, was highly controversial. Academic debates revolve around the verification of the points made, the historiographical relevance of the concept as a historical tool, and its profound nature. Nevertheless, the research associated with it is advancing our understanding of the relationships between the groups that made up medieval Spain, their dynamics, and the consequences of their interactions. These studies make al-Andalus one of the best-known medieval Islamic societies, both in written and archaeological terms [23].

These studies highlight the great variability of regimes and situations over time, the great dynamism of populations and regular mass conversions. Societies were organized by the juxtaposition of often rival, autonomous and unequal religious communities. Friction, tension and suspicion abound, exacerbated by conversions and fears of religious hybridization and miscegenation. Although cohabitation is not peaceful, there is no policy of persecution [24]. Convivencia between Christians, Jews and Muslims, precarious at best, is thus seen as an “uncomfortable necessity ” that goes hand in hand with the absence of declared legal principles, the consequences of which are harmful [25].

One of the reasons why historians have abandoned the concept of Convivencia is its proximity to contemporary notions among 21st-century audiences, leading to confusion and misunderstanding [26]. In French, for example, the term Convivencia has a strong but misleading etymological link with the positively inclusive political concept of “vivre-ensemble”. Yet the very notions of tolerance and “integration” were foreign to medieval thought. They were seen as a risk of weakening one’s own faith, of syncretism or even schism. The systems put in place served to delimit social categories, not to help them evolve. Communities live side by side, and firmly – and sometimes violently – combat any attempt at integration: marriage between members of different faiths is impossible, and sexual relations are punishable by death [27]. Moreover, by focusing on religions, the concept of Convivencia tends to overshadow other key elements structuring these medieval societies and their evolution: language, culture, ethnicity, gender, social status, age, etc. [28]

This cohabitation, however, induces new cultural forms at all levels of society and profoundly marks the history of Spain through the important periods during which it endures. The Arabic language was a major vector for the transmission and enrichment of knowledge in the West, thanks to translations into Latin and Romance languages which led to the majestic scientific deployment of the Renaissance, and, even earlier, to the so-called medieval renaissance of the 11th century [29]. Alongside academic debate, however, contemporary myths with political implications have developed on this historical substrate, much criticized for their lack of objectivity and rigor [30].

On the concept of the religious conviviality in al-Andalus David Bensoussan writes [31]:

”Al-Andalus, or Muslim Spain, became the paradigm of a unique conviviality between different religious communities, enabling an extraordinary flowering of literary, philosophical, scientific and legislative productions. It has remained as such in the memory of the Moors and Jews expelled by the advance of the Reconquest, and in the collective memory of the Islamic world from the Maghreb to India. It is still seen today as a model of cohabitation that is not only possible, but also desirable in our troubled times, when intercultural dialogue is advocated as a universal remedy, a fundamental tool for promoting mutual understanding, reconciliation and tolerance. The Roger Garaudy Foundation, based in Cordoba, and the Spirit of Cordova ecumenical movement are all inspired by his spirit”.

The Caliphate of Cordoba and the notion of conviviality (929-1031)

Situated in the West, in the province of al-Andalus, which it controlled entirely, the Caliphate of Cordoba was one of the most brilliant kingdoms of the Middle Ages: despite its short existence – scarcely more than a century – it succeeded in establishing itself as a major economic and cultural center, the bearer of an original civilization marked by the meeting of the Muslim East and the Christian West, and the crucible of an Arab thought that would enjoy a long posterity. Proclaimed in 929 by ‘Abd al-Rahmân III, a direct descendant of the Umayyads of Damascus who ruled the Muslim East until their defeat by the Abbasids in 750, it succeeded an emirate established in 756, barely forty years after the Arab conquest of the Iberian Peninsula [32].

Independent in every respect, the Caliphate of Cordoba was both a political and religious entity in its own right and, by its very existence, a radical challenge to the Abbasid Empire: with the establishment of the Caliphate, the Umayyads of the West launched a veritable attack on the Baghdad dynasty, already weakened by major internal dissensions. Last but not least, the Umayyad caliphate was the crucible of medieval Arabic thought, which was to enjoy a long posterity, both for its reflection on the Muslim religion and for its rediscovery of Greek philosophy: between Cordoba and Baghdad, between these two rival caliphates both intellectually bubbling, reciprocal influences were thus established, contributing to the formation of an Islamic culture in the broadest sense.

Finally, from the 9th century onwards – even before the establishment of the caliphate – Cordoba became a veritable cultural metropolis. Famous as far away as Central Asia for its brilliant intellectual milieu, it also enjoyed a reputation for hospitality that attracted many Eastern scholars and artists, encouraged by the tradition of patronage of the Cordovan emirs: the Iraqi musician Ziryab settled here during the reign of ‘Abd al-Rahmân II. Especially under al-Hakam II (961-976), literati, jurists, poets and intellectuals of all kinds from Iraq, Syria, North Africa and Egypt flocked to al-Andalus, where they were rapidly integrated into local society. On the one hand, this immigration demonstrated Cordoba’s brilliance in the 9th-10th centuries – which would continue even after the fall of the Umayyads – and, on the other, further encouraged cultural exchanges: the Andalusian aristocracy, under the influence of the new arrivals, adopted a lifestyle closer to that of the Baghdad court.

As a rival to the Abbasids and an enemy of the Fatimids, the Caliphate of Cordoba occupied a special place in the medieval Muslim world, and was above all the meeting place of East and West, as they were defined at the time. Small in size, it did not succeed – or even try – in eclipsing the immense Abbasid Empire, to which the Fatimids would deal a far greater blow. Nevertheless, its brilliant civilization was admired throughout the known world, as far away as Asia: culturally speaking, the mutual relations and influences between Cordoba and Baghdad were not only abundant, but extremely fertile, forming part of the vast model of a rich and diversified Islamic civilization.

On the subject of coexistence, Christine Mazzoli-Guintard wrote [33]:

“The coexistence of three cultures in the medieval Iberian Peninsula has long been the subject of debate, sometimes heated, always fruitful, as it leads to constantly renewed questioning. In the case of al-Andalus, the concept of harmonious interbreeding placed under the sign of tolerance was first replaced by that of living together, Convivencia, with diverse economic, social and artistic aspects, itself finally discarded in favor of the idea of coexistence between Jews, Christians and Muslims, summed up in the phrase “dos vecinos peleados coexislen, pero no conviven”. Traditionally, historiography contrasts the peaceful coexistence of the Umayyads in the 10th century with the rigorous coexistence of the Almohads, which, from the middle of the 11th century onwards, put an end, put an end to coexistence between the three cultures. Coexistence is also nuanced according to the social group in question: peaceful coexistence between the majority of people can go hand in hand with an avoidant coexistence thought out and desired by the law, as recent work on legal sources has highlighted. These are the many aspects of the coexistence of the three cultures that are examined here, through the three successive capitals of al-Andalus: Cordoba, Seville and Granada, as they allow us to examine the places where links are forged between individuals, from the myth of compartmentalized neighborhoods to the everyday realities of their mixed nature.”

The Spirit of Cordoba

Al-Andalus is the term used to designate all the territories of the Iberian Peninsula and parts of southern France that were, at one time or another, under Muslim rule between 711 (first landing) and 1492 (fall of Granada) [34]. Although a land of Islam dâr al-Islâm, the civilization of al-Andalus was cosmopolitan, made up of diverse populations with multiple origins and beliefs. Arabs, Berbers and muladi [35](or European Muslims, including Slavs or Saqalibas) were in the majority, but Jews and Christians also lived there.

It was a time when the three monotheistic religions met in peace for a fairly long time, allowing everyone – Muslims, Jews and Christians – to experience a general flourishing that extended to all areas of life and culture. In this way, it became possible to live together in a country where everyone found their place, bringing their own wealth and contributions. Some scholars refer to this flourishing period as the “Spirit of Cordoba“[36].

The Spirit of Cordoba represents a historical and intellectual movement rooted in the city’s rich cultural and scientific legacy, particularly during its time as a center of knowledge and innovation in Europe. This spirit symbolizes human excellence and ingenuity, and while much of the focus is on Cordoba, its influence also extended to other Spanish cities like Granada and Toledo.

Most academics agree that the Iberian Peninsula, under Muslim rule, experienced a veritable cultural apogee during the period of the Cordoba caliphate, a remarkable balance between its political and military power and the brilliance of its civilization: from the end of the 10th century, Spain welcomed the sciences and philosophy developed in the Islamic world by Muslim and Jewish scholars. Cordoba, 11th century: a landmark and a shining moment in the cultural history of mankind, where four centuries of al-Andalus civilization culminated. It is estimated that the first Jews arrived in Spain around 70 CE, after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. They welcomed the Arab conquerors at the beginning of the 8th century. Over the next three centuries, and until the fall of the Taïfas in 1086 (a group of independent emirates formed after the dissolution of the Caliphate of Cordoba in 1031), the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula reached such a high economic and social position, and Sephardic culture such a level, that this period is unanimously considered the golden age of Judaism worldwide.

Between the 11th and 14th centuries, Cordoba was an example of peaceful coexistence between the three great religions of the time: Jewish, Christian and Muslim. Cordoba, capital of the Umayyad caliphate, was the greatest economic and cultural center of the West, and attracted the patronage of poets and philosophers, men of letters and scientists of all persuasions.

Among them were Maimonides and Averroes, Jewish and Muslim thinkers, doctors, theologians and philosophers of the 12th century. But the arrival of the Almoravid dynasty in 1086 and the Almohad dynasty in 1146 marked the end of a long period of prosperity and peaceful coexistence between the different communities.

Violently forced to convert to Islam, the Jews fled Spain in their thousands, finding refuge in the Maghreb, Turkey and Greece… But these three centuries of harmonious coexistence between the three monotheisms remain to this day a long, happy interlude in the memory of European civilization, and have demonstrated to the world that our differences, far from opposing us, have the power, on the contrary, to bring us closer together, even to invite us to fraternize.

Al-Idrissi described Cordoba in the following words [37]:

“The city of Cordoba is the capital and metropolis of al-Andalus, and the seat of the Muslim caliphate. […] The central city is home to the Gate of the Bridge and the Friday Mosque 1, which is unrivalled among Muslim mosques for its architecture, ornamentation and size. […] This mosque has a qibla that is impossible to describe, so perfect is it. The mind is overwhelmed by the sight of its ornaments and all the gilded and colored mosaics that the emperor of Constantinople the Great sent to Abd al-Rahman nicknamed al-Nâsir li-Dîn Allah the Umayyad. On this side, I mean the side of the mihrab, there are seven arches rising on columns […] all enameled like an earring, with an art whose splendor of execution, nor finesse of realization, Christians, like Muslims, cannot reproduce.’

The golden age of Cordoba

The Spirit of Cordoba represents a historical and intellectual movement rooted in the city’s rich cultural and scientific legacy, particularly during its time as a center of knowledge and innovation in Europe. This spirit symbolizes human excellence and ingenuity, and while much of the focus is on Cordoba, its influence also extended to other Spanish cities like Granada and Toledo [38].

As to what concerns the contribution of Islam in the Iberian Peninsula, [39] Safvet Halilović argues [40]:

“Islam and its followers had created a civilization that played very important role on the world stage for more than a thousand years. One of the most important specific qualities of the Islamic civilization is that it is a well-balanced civilization that brought together science and faith, struck a balance between spirit and matter and did not separate this world from the Hereafter. This is what distinguishes the Islamic civilization from other civilizations which attach primary importance to the material aspect of life, physical needs and human instincts, and attach greater attention to this world by striving to instantly satisfy desires of the flesh, without finding a proper place for God and the Hereafter in their philosophies and education systems. The Islamic civilization drew humankind closer to God, connected the earth and heavens, subordinated this world to the Hereafter, connected spirit and matter, struck a balance between mind and heart, and created a link between science and faith by elevating the importance of moral development to the level of importance of material progress. It is owing to this that the Islamic civilization gave an immense contribution to the development of global civilization. Another specific characteristic of the Islamic civilization is that it spread the spirit of justice, impartiality and tolerance among people. The result was that people of different beliefs and views lived together in safety, peace and mutual respect, and that mosques stood next to churches, monasteries and synagogues in the lands that were governed by Muslims. This stems primarily from the commandments of the noble Islam according to which nobody must be forced to convert from their religion and beliefs since freedom of religion is guaranteed within the Islamic order.”

Cordoba, especially during its peak in the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 13th centuries), made several significant contributions to various fields of science and knowledge [41]. Here are some key contributions:

- Mathematics:

- Algebra: The mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, who worked in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad but had significant influence in Spain, is credited with the development of algebra. His works were translated and studied in Cordoba.

- Trigonometry: Muslim scholars in Cordoba made advancements in trigonometry, including the development of sine, cosine, and tangent functions, which were crucial for astronomy and navigation.

- Astronomy:

- Observatories: Cordoba housed observatories that allowed astronomers to study celestial bodies and improve astronomical tables.

- Astrolabes: Islamic scientists in Cordoba refined the astrolabe, an ancient device used for solving problems related to time and the position of the stars.

- Medicine:

- Medical Schools: Cordoba was home to one of the earliest medical schools in Europe. Scholars like Ibn Rushd (Averroes) made substantial contributions to medicine, including commentaries on Aristotle’s work and original research on various medical topics.

- Pharmacology: Medical texts compiled in Cordoba included extensive information on herbal medicine and pharmacology, influencing practices in both the Islamic world and later in Europe.

- Philosophy:

- Averroes (Ibn Rushd): A prominent philosopher from Cordoba, he bridged Islamic and Western thought, advocating for the study of Aristotle and influencing thinkers like Thomas Aquinas.

- Maimonides (Ibn Maimun): Another influential figure, he combined Jewish, Muslim, and Greek philosophies, impacting both Jewish and Islamic intellectual traditions.

- Architecture and Engineering:

- Innovative Techniques: The Great Mosque of Cordoba is not only an architectural marvel but also illustrates advanced engineering techniques like the horseshoe arch, which influenced later European Gothic architecture.

- Water Management: The development of irrigation systems and hydraulic engineering facilitated agriculture in the region, showcasing advanced understanding of water management.

- Literature and Translation:

- Translation Movement: Cordoba was pivotal in translating Greek and Roman texts into Arabic, preserving and enhancing classical knowledge that would later flow back into Europe during the Renaissance.

- Optics:

- Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen): Though born in Basra, his work in optics was influential in Cordoba. He laid foundational principles regarding light and vision, and his writings were studied widely.

- These contributions collectively fostered a culture of learning and intellectual exchange that made Cordoba a beacon of knowledge during the Middle Ages, laying the groundwork for future scientific advancements in Europe and beyond.

Symbiosis between the three monotheisms

Abd Arrahman an-Nassir came to power in October 912 at the age of 22. At the time, al-Andalus was experiencing serious problems of internal revolt, while threats from the Christian kingdoms to the north were real. But the young sovereign was as energetic as he was lucid. In just a few years, he put down the revolts, reunified the territory and inflicted defeat after defeat on the Christians in the north.

The young emir was beloved from the outset, granting complete freedom of worship, and maintaining contact with the great Jewish and Christian sages. He was a gentleman and a sincere believer in the principles of Islam; he loved religion, the arts and encouraged science. He knew that al-Andalus needed a perfect symbiosis between the three religions if it was to shine. The powerful Caliphate of Cordoba was proclaimed in 929.

Whereas they had been persecuted under the various Visigoth rulers, the Jews, now protected, were full-fledged citizens, powerfully organized as a community, erecting magnificent synagogues, developing culture and providing the state with great subjects; it was in al-Andalus that they lived best. The Hebrew community, with its sometimes very orthodox outlook, was not required to sacrifice any principles in order to participate in the cultural and political life of the country.

Golden age of Judaism

Al-Andalus was a Muslim country in the sense that religion dictated all laws, but Islam, recognizing other faiths, refused to interfere in the affairs of other cults.

As a result, the Jews, while speaking and writing Arabic, and adopting the Islamic style, developed their schools and teaching centers to perpetuate their religious heritage [42]. Better still, they were able to extend it. Great Jewish figures were thrust into the limelight, and the community was abuzz with interest in its own renaissance in a context that was largely favorable to it. This was truly the golden age of Judaism [43].

Entirely free in their worship, and untroubled by their beliefs, the Jews of Cordoba and other cities threw themselves into politics, art and economics. They translated philosophical texts for princes, wrote poems and literary texts of great finesse, opened major centers for the study of Talmud, supplied the country with large Arabic libraries, and rose to occupy positions at the top of the State [44].

On the golden age of Jewish culture, Mark R. Cohen writes [45]:

“In the nineteenth century there was nearly universal consensus that Jews in the Islamic Middle Ages—taking al-Andalus , or Muslim Spain , as the model—lived in a “Golden Age” of Jewish-Muslim harmony,1 an interfaith utopia of tolerance and convivencia. It was thought that Jews mingled freely and comfortably with Muslims, immersed in Arabic-Islamic culture, including the language, poetry, philosophy, science, medicine, and the study of Scripture—a society, furthermore, in which Jews could and many did ascend to the pinnacles of political power in Muslim government. This idealized picture went beyond Spain to encompass the entire Muslim world, from Baghdad to Cordova, and extended over the long centuries, bracketed by the Islamic conquests at one end and the era of Moses Maimonides (1138–1204) at the other.”

Intercultural blossoming

Hasdai Ibn Shaprut [46] is a famous example of this. Raised in orthodox Judaism, a talented physician and a great translator of Greek, he was a key figure in the caliphate’s ambassadorial missions and translations of Greek texts. In this way, he helped develop science independently of the Baghdad of the Abbasids, the main rivals. Respected by the authorities, Hasdai took the opportunity to develop Hebrew and the teaching of Judaism, and organized the Jewish community in a highly efficient manner.

Mozarabic Christians (living in al-Andalus) also flourished, occupying key positions with the authorities in the same way as Jews, and were sometimes responsible for foreign policies. In many cases, they were the Caliph’s ambassadors to the Court of Constantinople, like the bishops Racemundo and Rabi ibn Zayd.

At the same time, numerous Muslim scholars excelled in all fields. Debates were fierce and critical thinking lively. New discoveries came thick and fast, and al-Andalus became the most scientifically fertile place in the world. Jews and Christians, subject to the dhimmi (protected) tax, and Muslims subject to the zakât (third pillar of Islam) tax, together gave rise to a society that was exemplary in terms of intercultural flourishing.

Convivencia erased by the Inquisition

You can travel the length and breadth of al-Andalus, from north to south and east to west, and despite their historical, social and economic importance in the Spain of the three cultures, you’ll rarely, if ever, find a trace of the Jews’ passage through these regions.

This is hardly surprising, given that the Jews were never great builders: you don’t see grand edifices such as the Mosque of Córdoba, for example, or palaces like the Alhambra in Granada. This is also due to the fact that the religious buildings of the Jewish faith, the synagogues, are fairly sober places, uncluttered by pompous ornamentation. On the other hand, they played an important financial role, as they always do, as advisors to the emirs.

One of the best examples is Hasdaï ibn Shaprut, mentioned above, protector of the Jewish community, physician, diplomat and adviser to Abd al Rahman. This is truly the symbol of a century which, despite the tensions that still existed, was one of tolerance and respect for others, which prevailed over identity or religious values, and where the three religions of the Book coexisted in harmony; in short, what has sometimes been called “the Spirit of Cordoba”, which prevailed until a certain period [47].

Medieval Spain can and must inspire us, not just by promoting a “tolerance” that would set aside religious truths, syncretism or indifference, but rather because it was first and foremost “a land of dialogue”, often bitter, sometimes violent, but also extraordinarily rich.

In fact, the Jews were a rather urban community. They lived in what were known as “juderías“, districts they occupied, separated from Christians and Muslims, and which often constituted a veritable municipality within a municipality. They had, for example, their own independent judiciary.

Some Jews thus occupied positions of great responsibility in the administration and government, given their intellectual training and their skill in handling money: loans and usury. The lowest social classes were made up of small craftsmen and tradesmen. But the jealousy provoked by their wealth and popular hatred, combined with religious intransigence, meant that in the 14th century, certain Jewish quarters were attacked and disappeared. Towards the end of the same century, many were forced to convert to Christianity. They became known as “conversos“, which led to the decline of the “juderías“. These “Spanish Jews” (Sefarad or Sephardis, the Hebrew name for Spain) included Fernando de Rojas, author of La Celestina, Fray Luis de León, Mateo Alemán, Spinoza…

In 1492, tolerance disappeared once and for all when the Catholic Monarchs decreed the conversion or expulsion of Jews, who left Spain and emigrated to Portugal, North Africa, Turkey, the Balkans and Italy. It is estimated that over 150,000 Jews left Spain at this time. A little later, it was the turn of the “moriscos” [48], the Muslims who remained in Spain after the fall of Granada, the last Muslim kingdom. Despite earlier promises, the Muslims retained their language, religion and customs, and due to the numerous problems and uprisings, King Felipe II ordered their definitive expulsion in 1609. Over 300,000 Muslims left the country and settled permanently in the Maghreb. Even today, legend has it that certain families in Tlemcen or Fez jealously guard in velvet cases the keys to the homes they left in a hurry when they were expelled, and there are still family names in Algeria such as “Kortebi” or “Benkartaba” (from the Arabic pronunciation of Cordoba, Córdoba, Kortoba).

And all this, of course, thanks to the good offices of the Spanish Holy Inquisition, created by the Catholic Monarchs in 1480 to consolidate religious unity. The famous Inquisition tribunal was headed by an Inquisitor General, the most famous of whom was the infamous Fray Tomás de Torquemada, who prosecuted Jewish communities. He finally decreed, in 1492, the expulsion of those who did not want to be baptized, which led to the loss of a social group that was very active, as I have already pointed out, in trade, finance and banking. Torture and violent interrogation were common practice, while death at the stake was often the sentence.

In short, the Inquisition was used politically to reign terror and combat modern ideas, those of Muslims, Protestants, sects…, and the persistence of Judaizing practices, as well as, to a lesser extent, to repress acts that deviated from strict orthodoxy (blasphemy, fornication, bigamy…).

Mohamed Chtatou

References

[1] “La Convivencia occitane” refers to a period of cultural and religious tolerance in Occitania, a region in southern France. This concept highlights the coexistence of different faiths, particularly Christianity and Islam, during the Middle Ages. It is believed that the term Convivencia itself originated in Occitania, reflecting the region’s unique social fabric.

[2] Garcia, Alem Surre. (2025). Au-delà des rives – Les Orients d’Occitanie. Paris: France, Dervy.

[3] The Cahiers are a collection of notes and reflections recorded by French philosopher Simone Weil between 1933 and 1943, published from 1950 in several volumes by two different publishers, Plon and Gallimard. A four-volume critical edition was published in Volume VI of the author’s Œuvres complètes by Gallimard between 1994 and 2006.

Cf. Weil, Simone. (2014). The Notebooks of Simone Weil. Translated from the French by Arthur Wills. London, UK: Routledge.

[4] Garcia, Alem Surre. (2023). La Convivéncia. Montséret, France : Troba Vox.

[5] Dhimma is an Arabic term designating the legal status of any citizen of a Muslim state who is not of the Muslim faith. Dhimmis (people subject to dhimma) are subject to specific taxes in Muslim states.

From Arabic ḏhimma, ذمة, (“commitment”, “pact”, “obligation”).

The institution of dhimma, a pact of reciprocal obligation between non-Muslims recognized as “People of the Book” and the theocratic Muslim state, which established a discriminatory but “protected” status for the latter, governed the condition of those known as “dhimmî” from the 7th century until the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Cf. Pascal Buresi, Pascal. (2013). La ḏimma et les ḏimmī à travers l’histoire : problèmes et enjeux. In Être non musulman en terre d’Islam. Dhimmi d’hier, citoyen d’aujourd’hui ? (pp. 7-14). Paris, France : Editions du Cygne. ffhalshs01440062f

[6] The jizyah (Arabic: جزية ), is in the Muslim world an annual capitation tax referred to in the Qur’an and collected from pubescent non-Muslim males (dhimmîs) of military age in return for their protection – in principle. Certain dhimmîs are theoretically exempt: women, children, the elderly, the infirm, slaves, monks, anchorites and the insane. Those dhimmîs who are authorized to bear arms for military service are also exempt, as are those who cannot afford to pay it, according to some sources

[7] Dodds, J.D. & Glick, T.F. (eds.). (1992). Convivencia: Jews, Muslims and Christians in Medieval Spain. V.B. Mann, New York: George Braziller & The Jewish Museum.

[8] Barrio, R. S. (2010). La convivencia. Interroger la coexistence. In D. Do Paço, M. Monge, & L. Tatarenko (éds.), Des religions dans la ville (1‑). Rennes, France : Presses universitaires de Rennes. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.129558

[9] Romano, D. (1995). Coesistenza/convivenza tra ebrei e cristiani ni ispanici. Sefarad, 55, 359-382.

[10] Bensoussan, David. (2007). L’ESPAGNE DES TROIS RELIGIONS. Grandeur et décadence de la convivencia. Paris, France : L’Harmattan, collection : Religions et Spiritualité.

[11] Glick, T. (1992). Convivencia: An Introductory Note. In V. B. Mann, T. F. Glick & JD Dodds (Eds.), Convivencia: Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain (pp. 1-9). New York, NY, US: George Braziller.

[12] Burns, R. (1984). Muslims Christians, and Jews in the Crusader Kingdom of Valencia: Societies in Symbiosis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[13] Castro, Américo. (1948 (1983)). España en su historia. Cristianos, moros y judíos. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Editorial Losada. Reprint, Barcelona, Spain: Crítica.

[14] Castro, A. (1948). España en su Historia. Mexico City, Mexico: Porrúa.

[15] Araya Goubet, G. (1976). The Evolution of Castro’s Theories. In JR Barcia (Ed.), Américo Castro and the Meaning of Spanish Civilization. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[16] Castro is generally seen as the father of Convivencia; Alex Novikoff, however, observes that Castro borrowed the term from the philologist Ramón Menéndez Pidal. See Novikoff, Alex. (2005). Between Tolerance and Intolerance in Medieval Spain: An Historiographic Enigma. Medieval Encounters, 11(1). See Hartman, Abigail. (2016). ANYTHING AND EVERYTHING”: THE PROBLEMATIC LIFE OF CONVIVENCIA. Furman University Scholar Exchange, pp 18 & 20 for a discussion of Pidal’s contributions to Spanish historiography and Castro’s revisionist response. Retrieved from https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=fhr

[17] Of the cultural efflorescence during the reign of Alfonso X “The Learned,” for example, Castro writes, “Arabic sciences and technical knowledge were imported by the Castilian Christian because of their practical and artistic efficacy. . . The Jew served as an intermediary between the Moor and the Christian in many ways, and through him the Castilian of the dominant caste was able to become master of his lands, conqueror of the Moor, and eventually executor of the Hispano-Hebrew prophecies of imperial dominion of the world.” Castro, The Spaniards, p. 539 (see below the full reference of the book in question).

[18] Castro, Américo. (1971). The Spaniards: An Introduction to Their History. Translated by Willard F. King and Selma Margaretten. Berkeley, CA, US: University of California Press.

[19] Mudéjar art refers to a distinctive style of Iberian architecture and decoration that emerged during the Middle Ages, blending elements of Islamic, Christian, and Jewish art. The term “Mudéjar” originally referred to Muslims who remained in Spain after the Christian Reconquista, and their artistic contributions significantly influenced the architectural and decorative landscape of the region. In architecture, the Mudejars used their own techniques (horseshoe arches, blind arcatures, minaret-shaped bell towers) and their own ornamentation: arabesques, coffered ceilings (artesonados) with marquetry. Applied to Romanesque, especially Gothic and Renaissance buildings, these elements produced a hybrid style. Its main features are the horseshoe arch, the use of bricks, and decoration in polychrome chased plaster (yeserias) and ceramics (azulejos). It’s the use of art techniques brought by Muslims to buildings built by Christians.

[20] Wolf, K. B. (2009). Convivencia in medieval Spain: A brief history of an idea. Religion Compass, 3(1), 72-85. Retrieved from https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00119.x

[21] Meyuhas Ginio, A. (1998). Convivencia o coexistencia? Acotaciones al pensamiento de Américo Castro. In Carrete Parrondo C., Meyuhas Ginio A. (Ed.), Creencias y culturas. Cristianos, judíos y musulmanes en la España Medieval (p. 147-158). Salamanque, Spain : Universidad Pontífica de Salamanca.

[22] Fernand, Niel. (1955). Albigeois et cathares (p. 25). Paris, France : PUF. “Albigeois et cathares” is a book published by Presses Universitaires de France (PUF) in 1955. It is likely a historical study about the Albigensian Crusade and the Cathar movement in the Languedoc region of southern France

[23] Soifer, Maya. (2009). Beyond Convivencia: Critical Reflections on the Historiography of Interfaith Relations in Christian Spain. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies, 1(1), 19-35.

[24] Chtatou, Mohamed. (2020). Al-Andalus: Glimpses of Human Coexistence and Compassion – Analysis. Eurasia Review. Retrieved from https://www.eurasiareview.com/19102020-al-andalus-glimpses-of-human-coexistence-and-compassion-analysis/

[25] Ray, J. (2006). Beyond Tolerance and Persecution: Reassessing Our Approach to Medieval Convivencia. Jewish Social Studies, 11, 1–18.

[26] Gómez-Martínez, JL. (1975). Américo Castro y el Origen De los Españoles: Historia De una Polémica. Madrid, Spain: Gredos.

[27] Bejczy, István. (1997). Tolerantia: A Medieval Concept. Journal of the History of Ideas, 58(3), 365-84.

[28] Cailleaux, Christophe. (2013). Chrétiens, juifs et musulmans dans l’Espagne médiévale. La convivencia et autres mythes historiographiques. Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 86. Retrieved from http://journals.openedition.org/cdlm/6878 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/cdlm.6878

[29] Menocal, M. R. (2002). The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Co.

[30] Sánchez-Albornoz, C. (1929). España y el Islam. Revista de Occidente, 24, 1-30.

[31] Von Kemnitz, Eva-Maria. (2008). David Bensoussan, L’Espagne des trois religions. Grandeur et décadence de la convivencia. Archives de sciences sociales des religions, 144(7), 163-274. Retrieved from http://journals.openedition.org/assr/18653 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/assr.18653

[32] Lévi-Provençal, Evariste. (1953). Histoire de l’Espagne musulmane. 2., Le califat umayyade de Cordoue (912-1031) et 3., Le siècle du califat de Cordoue (p.431, p. 577). Paris, France : G.-P. Maisonneuve.

[33] Mazzoli-Guintard, Christine. (2009). Cordoue, Séville, Grenade : mythes et réalités de la coexistence des trois cultures. Horizons Maghrébins – Le droit à la mémoire, 61, 22-29. Retrieved from https://www.persee.fr/doc/horma_0984-2616_2009_num_61_1_2792

[34] Arigita, E. (2013). The ‘Cordoba Paradigm’: Memory and Silence around Europe’s Islamic Past. In F. Peter, S. Dornhof & E. Arigita (Ed.), Islam and the Politics of Culture in Europe: Memory, Aesthetics, Art (pp. 21-40). Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/transcript.9783839421765.21

[35] The word muladi (Spanish: muladí, muladíes in the plural) comes from the Arabic مُوَلَّد, muwallad, meaning: adapted or mixed. The term has two closely related meanings that tend to define the identity of a non-Arab person converted to the Muslim faith during the al-Andalus era. In Muslim Spain, this term was used in two ways:

- The Christian who abandoned Christianity, converted to Islam and lived among Muslims. He differed from a Mozarab because the latter retained his Christian religion in areas under Muslim domination.

- The son of a mixed Christian-Muslim couple of Muslim faith.

Muladi refers to individuals in medieval Islamic Spain (al-Andalus) who were of mixed ancestry, particularly those who were converts to Islam from Christianity or were descendants of such converts. The term derives from the Arabic word “muwallad,” which means “born of a mixed lineage.” Many muladis remained in Iberia and played significant roles in the cultural and social landscapes of medieval Spain, with some converting back to Christianity over time.

[36] Halilović, Safvet. (2017). ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION IN SPAIN – A MAGNIFICIENT EXAMPLE OF INTERACTION AND UNITY OF RELIGION AND SCIENCE. Psychiatria Danubina, 29(1), 64-72.

[37] Al-Idrîsî. (1154). Nuzhat al-mushtaq fî ikhtirâq al-âfâq, also known as the Book of Roger. Sicily.

[38] Ofek, Hillel. (2011). Why the Arabic World Turned Away from Science. The New Atlantis, 30, 3-23. Retrieved from https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/why-the-arabic-world-turned-away-from-science

[39] Hajar R. (2013). The Air of History Part III: The Golden Age in Arab Islamic Medicine An Introduction. Heart views : the official journal of the Gulf Heart Association, 14(1), 43-46. https://doi.org/10.4103/1995-705X.107125

[40] Halilović, Safvet. (2017). Op. cit., p. 64.

[41] Matthew E. F.; Zarkadoulia, E. A. & Samonis, G. (2006). Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 C.E.) and today. FASEB journal.

[42] Chtatou, Mohamed. (2021). The Golden Age of Judaism in Al-Andalus (Part I) – Analysis. Eurasia Review. Retrieved from https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-golden-age-of-judaism-in-al-andalus-part-1/

Chtatou, Mohamed. (2021). The Golden Age of Judaism n Al-Andalus (Part II) – Analysis. Eurasia Review. Retrieved from https://www.eurasiareview.com/24112021-the-golden-age-of-judaism-in-al-andalus-part-ii-analysis/

[43] Pelaez de Rosal, Jesus. (2003). (ed.). Les Juifs à Cordoue (Xe-XIIe siècle). Córdoba, Spain: Edicones El Almendo.

[44] Cohen, Mark R. (1994). Prologue. The “Golden Age” of Jewish-Muslim Relations: Myth and Reality. Asset Press Princeton Edu., 28-38. Retrieved from https://assets.press.princeton.edu/chapters/p10098.pdf

[45] Ibid. p. 28.

[46] Hasdaï ibn Shaprut (Hebrew: חסדאי בן יצחק בן עזרא אבן שפרוט Hasdaï ben Yitzhak ben Ezra ibn Shaprut; Arabic: حسداي بن شبروط ) was a 10th-century Jewish physician, diplomat and patron of the arts (born c. 915 in Jaén – died c. 970 in Cordoba). According to Heinrich Graetz, he was the main promoter of the revival of Jewish civilization in Spain.

His father was a well-off, well-educated Jew from Jaén. In his youth, Ḥasdaï acquired a complete knowledge of Hebrew, Arabic, Greek and Latin, the latter being known at the time only to the Spanish high clergy. Studying medicine, he is said to have rediscovered the composition of a panacea known as “Al-Farouk” (i.e. theriac). As a result, he was appointed physician to the Umayyad caliph of Cordoba, Abd al-Rahman III, becoming the first Jew to hold such a position.

His manners, knowledge and personality won him the favor of his master, and he became his confidant and faithful adviser. Although he could not be appointed vizier because of his Jewishness, he unofficially performed the duties of vizier. He was responsible for foreign affairs, as well as customs and docking rights in the port of Cordoba, the main route for foreign trade.

[47] Manzano Moreno, E. (2013). Qurtuba: some critical considerations of the Caliphate of Córdoba and the myth of convivencia. Madrid, Spain: Casa Árabe e Instituto Internacional de Estudios Árabes y del Mundo Musulmán.

[48] The term “Morisco” (from the Spanish morisco) refers to Muslims in Spain who converted to Catholicism between 1499 (campaign of mass conversions in Granada) and 1526 (following the decree expelling Muslims from the Crown of Aragon). It also refers to the descendants of these converts.

While Mudejars were Muslims living under the authority of Christian kings during the reconquest of Spain (completed in 1492 with the capture of Granada by Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, the Catholic Monarchs), Moriscos were Christians, formerly Muslims or descendants of converted Muslims. Strictly speaking, therefore, they do not form a clearly defined religious or ethnic minority. Between the period of the initial conversions (1499-1502 for the Crown of Castile, 1521-1526 for the Crown of Aragon), and the general expulsion of the Moriscos in 1609-1614, several generations followed one another, more or less close to Arab-Muslim culture, more or less assimilated into the Christian majority society. Regional differences were also significant, with varying degrees of assimilation.

No Comments