The great Syrian poet Adonis talks about Islam in two books of interviews. His conversations are filled with interpretations and reductionisms about religion, the Arab world and the history of Islam.

Suleima Mourad*

In the 19th century, impressed by European modernity and its achievements, intellectuals in the Muslim world were divided into three currents. On the one hand, secularists such as Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani in Iran and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s movement in Turkey held Islam responsible for the backwardness of Muslims. They gradually abandoned religion and adopted Western thought and dress.

Modernists such as Jamal Al-Din Al-Afghani (Iran) and Muhammad Abduh (Egypt) advocated reforms while maintaining the “fundamental” ideas of Islam. These authors, however, disagreed on the nature of these fundamental ideas and on the reforms that needed to be undertaken.

For their part, Muslim fundamentalists, such as Rashid Rida in the Arab world or Aboul Ala Maududi in South Asia, insisted that Islam was perfect and timeless. If Muslims had problems (economic, political, military, etc.) it was their fault for not adhering strictly to the teachings of Islam.

Each of these three currents invented a golden age, just as the Europeans did during the Renaissance. The secularists went back to pre-Islamic times, looking for models on which to base their modern fantasies. Modernists picked up historical fragments from the origins of Islam and turned them into emancipatory manifestos. The fundamentalists focused on Mohammed and his companions, aiming to recreate the “purity” and “transformative” power of their movement.

A determining influence on Arabic literature

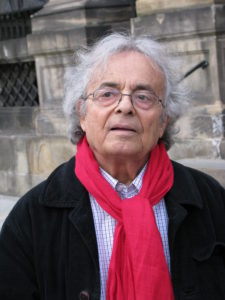

The great poet and intellectual Adonis belongs to the first group. Born Ali Ahmed Said Esber in 1930 to an Alawite family in northwestern Syria, he adopted the pseudonym Adonis (after the god of the ancient Near East) in the late 1940s. In 1956, he moved to Beirut, after spending a year in prison for political reasons, due to his membership in the Pansyrian nationalist party, Syrian Nationalist Social Party (SNSP). In Beirut, he launched two literary magazines, Shi’r (“Poetry”) and Mawaqif (“Points of View”), which became major benchmarks of Arab modernism. He also produced a steady stream of radical poetry and literary criticism, which has led some authors to compare his influence with that of T.S. Eliot in the English-speaking world. His best-known works are the collection of poems Songs of Mihyar the Damascene (1961) and the four-volume critical study Al-thabit wa al-moutahawil (1974-1978).

The great poet and intellectual Adonis belongs to the first group. Born Ali Ahmed Said Esber in 1930 to an Alawite family in northwestern Syria, he adopted the pseudonym Adonis (after the god of the ancient Near East) in the late 1940s. In 1956, he moved to Beirut, after spending a year in prison for political reasons, due to his membership in the Pansyrian nationalist party, Syrian Nationalist Social Party (SNSP). In Beirut, he launched two literary magazines, Shi’r (“Poetry”) and Mawaqif (“Points of View”), which became major benchmarks of Arab modernism. He also produced a steady stream of radical poetry and literary criticism, which has led some authors to compare his influence with that of T.S. Eliot in the English-speaking world. His best-known works are the collection of poems Songs of Mihyar the Damascene (1961) and the four-volume critical study Al-thabit wa al-moutahawil (1974-1978).

In the mid-1980s, when the Lebanese crisis worsened, Adonis moved to Paris, where he has lived ever since. However, he has not ceased to be an essential reference in the Arab literary scene, mainly because of his views on Islam, which he often expresses and which have always been controversial, to say the least. This issue is revisited in two new books, published in the form of conversations with the French-Moroccan psychoanalyst Houria Abdelouahed, under the French publishing label Seuil: Violence and Islam (2015) and her second volume Prophecy and power (2019). These books illustrate well the difficult position of many secularist Muslim intellectuals, who idealize European ideas while displaying an ironic condescension toward their own society.

First, these talks are full of historical errors. For example, Adonis claims that Islam rejects and even destroys sculptures and images, which is not true. Some Muslims have banned and continue to ban images, but others (including Sunnis and Shiites) have produced countless images and illustrations, even of the Prophet Mohamed. Also, poetry is not “frowned upon in Islam,” and many of Mohammed’s close companions were poets. Moreover, Muslims produced more poetry, sometimes religious, than any other culture before the modern era. This claim by Adonis is all the more shocking considering that he has published an anthology, in three volumes of Arabic and Islamic poetry (Diwan al-shi’r al-‘arabi [Anthology of Arabic Poetry]).

Nor is it true that Sufism is “opposed to what we call Islamic culture”. On the contrary, in most Muslim countries it is inseparable from Islamic culture. Similarly, to say that “Arab Islam has rejected the West” does not correspond to the facts. Since the 19th century, we find a large number of Islamic discourses that are inspired by and imitate the West: the reforms (tanzimat) in the Ottoman Empire, the religious modernism of Al-Afghani and Mohamed Abduh, Qasim Amin’s notion of women’s liberation (which does not impress more recent feminists, especially his belief that women need to be educated in order to form leaders), Mohamed Iqbal’s Islamic humanism, etc.

Equally erroneous is Adonis’ view of the flag of the Islamic State (IS) organization, which he misinterprets: he mistakenly believes that it bears the slogan “God is the messenger of Mohamed,” so he interprets IS members as thinking that God is in the service of Mohammed. In reality, the slogan reproduces the Prophet’s ring in which the slogan – “Mohamed is the messenger of God” – is written vertically from bottom to top to ensure that God’s name is mentioned before the Prophet’s (a fact that Adonis seems unaware of); his interpretation of the notion of Mohamed as the seal (khatam) of the prophets, etc.

A religion imposed by the sword?

The errors are too numerous to list. The books also contain innumerable conceptual errors, the worst of which is the idea that Islam was spread by force. In reality, what we commonly call the Islamic conquests were not religious in nature. There is no evidence that the men who left Arabia in 630 sought to convert the conquered peoples. On the contrary, the Arabs of the time sought to prohibit the conversion to Islam.

The errors are too numerous to list. The books also contain innumerable conceptual errors, the worst of which is the idea that Islam was spread by force. In reality, what we commonly call the Islamic conquests were not religious in nature. There is no evidence that the men who left Arabia in 630 sought to convert the conquered peoples. On the contrary, the Arabs of the time sought to prohibit the conversion to Islam.

On the other hand, the early manuals of Islamic law record numerous debates among jurists on the protection granted to the “People of the Book” (Christians and Jews) living under Islamic rule, and whether it should be extended to non-monotheists (Zoroastrians, Hindus, etc.).

It cannot be denied that some verses of the Koran preach violence against non-believers. But the text is very hesitant. Verse 9:29 is a good example, when it calls Muslims to fight against the People of the Book. However, it does not allow them to kill, harm or convert them. They can only impose a tax on them. Likewise, the Qur’an states that the religion with God is Islam (which term in the Qur’an means “submission to God,” something Adonis seems to be unaware of). However, the Qur’an also states: “To each of you We have given a rule and a way. Allah, if He had willed, would have made of you one community”. The text is riddled with hesitations or inconsistencies, as if torn between harshness towards non-believers and the desire to offer them a new opportunity to repent.

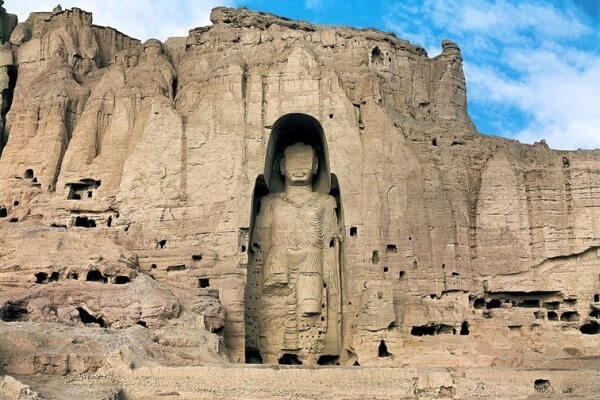

The historical practice of Muslim rulers in the Middle Ages, except in exceptional cases, shows that non-Muslim communities were tolerated. In fact, the Arab Middle East remained predominantly Christian until the 12th century, a fact that Adonis and Houria Abdelouahed seem to completely ignore. In some non-Arab regions, Muslims remained a minority until the dawn of the modern era. One can think of the Yezidis of northern Iraq, who have lived through hell at the hands of IS. They thrived in the heart of the Islamic world, along the busiest road, linking East and West. If Muslims wanted to purge the world of anything that did not conform to their ideology, as Adonis and Abdelouahed claim, why did they leave the Yezidis alone? Why did Egypt remain predominantly Christian until the 14th century? Why were Jews allowed to live and thrive throughout the Muslim world? Why did the Buddha statues in Afghanistan remain intact until the Taliban destroyed them in 2001?

These facts highlight a further problem with Adonis and Abdelouahed’s historical perspective: they project the views held by groups like IS as if Muslims as a whole had always advocated them. In fact, militant Islam is a recent ideology, a product of political dynamics, and especially of decades of exploitative policies by the West, the USSR and local regimes. It is well known that the United States allied itself with militant Islam to destabilize certain regimes in the Arab world and to combat the spread of communism. Some of these regimes have played with Islamic fundamentalism to score points against their rivals. Didn’t Anwar Sadat release Muslim fundamentalists to wipe out leftist university student organizations in Egypt? Didn’t Bashar Al-Assad release thousands of Islamists from their prisons to move to Iraq to fight the US invasion? And what about Pakistan and its support for militant Islamism to counter the influence of India? Islamism is not an organic continuation of the medieval Islamic tradition, it is a political creation.

Islamism is not an organic continuation of the medieval Islamic tradition, it is a political creation.

Adonis states that “all those who wrote works in the field of poetry, philosophy, music, etc., those who built Islamic culture or Arab civilization, were not Muslims in the traditional sense of the word.” Does this mean that poets like Rûmî or the philosophers Avicenna and Averroes were not true Muslims? Undoubtedly, they addressed the question of what it means to be a Muslim and how to know the Creator, and their answers contributed to enriching the Islamic tradition.

Rationalist philosophers, such as Avicenna and Averroes, claimed that God had endowed human beings with a rational mind, which could lead believers to Him. They studied ancient philosophy in the hope that it would help them solve deep religious questions, and they had to make it fit into monotheism to be useful. When Thomas Aquinas wanted to harmonize Aristotelian philosophy with the principles of Christianity, he turned to Avicenna and Averroes (the real contribution of Islamic philosophy is a subject that many scholars still refuse to discuss, beyond a simple footnote). Averroes was also a great jurist in the Sunni tradition. His legal encyclopedia, Bidayat al-mujtahid wa-nihayat al-muqtasid (“Primer of the Discretionary Scholar”) is a reference work, in four volumes, on the Shari’ah. If this is not traditional Islam, what is?

A multiple tradition

The opinions of Adonis and Abdelouahed might be acceptable in bar discussions. But when published for wide dissemination, they become weapons of misinformation and stigmatization.

My rhetorical question goes to the heart of the problem raised by Adonis’ essentialist musings. Islam is not a fixed thing and has never been a single thing. Islam has always had several discourses. The Qur’an is full of contradictions, and not because its author was confused. Anyone who has to deal with idealism and realism encounters contradictions. Islamic tradition (including the Hadith) recognizes that there was no Qur’an as a text when Muhammad died in 632. The official codex was not written until about twenty years after his death. Muslims eventually agreed on a basic text, but never on how to read and interpret it. As for the hadith (or [Sunna]), they never agreed on even a basic text. This is the Islamic tradition.

The idea that Islam can be accurately determined on the basis of what the Qur’an teaches is a modern dogma, inspired by the “Protestanization” of the world’s religions, and the false claim that each should focus on its own sacred scripture. In reality, the divine texts of each religion are read alongside other texts. For example, in traditional Judaism, without the Mishna (called the Oral Torah), it is impossible to understand the Hebrew Bible. In Islam, the Sunna of the Prophet Mohammed occupies a similar position for most Sunnis. Shiites, on the other hand, refer to their imams, whom they call “the speaking Qur’an” (al-qur’an al-natiq) because they pronounce that which is hidden in the text. In addition, Muslims developed a complex science called tafsir (written exegesis) in order to deduce from the Qur’an the meanings they wanted to find in the divine text.

We also find clear evidence that Muslim jurists “manipulated” their construction of Islamic law. Their most popular prophetic hadith was: “Seek knowledge even in China”, which they understood as an encouragement to seek knowledge, rather than passive imitation of Mohamed. Contrary to what Adonis says, for them, Mohamed was not “an absolute, ultimate and supreme authority”. Numerous jurists rejected blind adherence, often deploying a rational quest. The jurist Al-Shatibi (d. 1388) summed it up perfectly, “Whatever is not explicitly stated in a revealed text, but can be arrived at by deduction, is God’s intention.”

This influence endures to this day. Subhi Al-Salih (d. 1986), vice president of the Shi’i Islamic High Council of Lebanon, was one of the most influential traditional Sunni jurists in the Arab world. He stated that his motivation for writing his book The Characteristics of Islamic Shari’ah (in Arabic) was to “free” Islamic law from “complex issues” and adapt it “to the spirit of the times.” He went so far as to state that “the Shari’a is immaculate from the eternal beginning and is perpetually renewed.” It does not take a genius to understand what Al-Salih meant: if the sharia is “immaculate”, it does not need to be renewed. The fact that it needs renewal means that it will be the jurists who will do the job, not God or Mohamed.

Condemnation of the Arab Spring

It would do us good to hear that his generation of Muslim secularists would have acted differently had they been able to repeat his experience.

Secularists like Adonis gambled on Western modernity, which they believed would “liberate” the Arab and Muslim world, but they were slow to realize that this was primarily a discourse of subjugation. Dreams of emancipation led to difficult situations, which most consumers of Western modernity face today. However, despite the popularity of socialism and secular nationalism in the Arab and Islamic world in the decades after World War II, secularists failed to achieve their promises of emancipation and freedom. Since the 1980s, they have been gradually overtaken by a new generation of Islamic modernists offering their own vision of progress, be they intellectuals like Amr Khaled or political leaders like Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, -if we take into account their manipulative policies. Their success depends on numerous factors, including the versions of Islam they develop.

This explains, in part, why Adonis condemned the Arab Spring. After initially applauding the protesters (especially in Tunisia and Egypt, where many thought Arab secularists would return to their golden age), Adonis lost his enthusiasm when it became clear that the Islamists were taking the lead. He repeated that Arabs are incapable of producing anything but oppressive regimes, a neurosis he attributed to Islam.

But ideologies and belief systems do not predetermine behavior. On the contrary, people take hold of ideologies and play with them to one side or the other to achieve their own goals. However, the Syrian rebels did not adhere to the mosque. It was the only space left to them, and the brutality of the regime, coupled with the cynicism of intellectuals like Adonis, led many of them to extremist organizations like Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, or to other forms of political exploitation staged by Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the United States, Russia, etc.

Adonis disappoints us by missing the opportunity to reflect on the reasons why his generation, which achieved so much in the 1960s and 1970s, has difficulty resonating with Arab and Muslim youth today. Abdelouahed asks him, “What have you lost?” He replies, “The only thing I have lost is my old age. It would do us good to hear that his generation of Muslim laymen would have acted differently had they been able to repeat his experience. Blaming their failures on Islam does not show great intellectual courage.

Today’s young Muslims do not share Adonis’ rigid separation between Islam and modernity. Muslim feminists like Leila Ahmed, Fatima Mernissi and Amina Wadud have drawn on history and religious thought to promote women’s emancipation. Gay Muslims such as Scott Siraj Al-Haqq Kugle and French-Algerian imam Ludovic Mohamed Zahed have explored sexuality through the lens of the Quran and Islamic law to demonstrate that there is a space for them in Islam. Similar developments are taking place in Islamic banking (Western banking with an Islamic terminology), political liberalism, human rights, and a host of other issues. Seemingly oblivious to these conversations, Adonis and Abdelouahed repeat old clichés. The practices of IS or those of certain rural areas are not representative of all Islam.

Adonis and Abdelouahed’s views might be acceptable in bar discussions. But when published for wide dissemination, they become weapons of disinformation and stigmatization.

*Suleiman Mourad is a professor at Smith College (USA). He is co-author, with Perry Anderson, of “The Mosaic of Islam”, sigloXXI, 2018.

Source: Orientexxi.info

No Comments