The goal of this talk, presented by Alfonso Casani, researcher at the Islamic Culture Foundation as part of the conference “Conversations on Islamophobia and Gender”, organized by Casa Arabe and the Group for the Analysis of Islam in Europe (GRAIS), is to offer a cultural approach to the fight against Islamophobia. By highlighting and analyzing some of the different campaigns that have tried to influence on the social processes of inclusion/exclusion of Muslims by society, this talk deepens on the different attempts at reinterpreting the cultural and historical facts that link Spain’s past to an Islamic civilization that have taken place in the last years.

Islamophobia has been growing since the beginning of this century, with a first wave after the September 11th attacks, and a current second one since the appearing of Daesh and the spreading of terrorist attacks through Europe and North America. Citizen Platform against Islamophobia informs of 546 reported attacks to the Muslim population in Spain, both physical and online attacks. In this sense, the latest European Islamophobia Report points out at two different types of Islamophobia: the “institutionalized islamophobia”, understood as the Islamophobic decisions taken and implemented by the State (Aguilera-Carnerero, 2017), and which rely in the cultural roots of Islamophobia in the country; and the “citizen’s Islamophobia”, everyday attacks and verbal abuses promoted by the regular citizen.

From this perspective, we consider it necessary to tackle institutionalized islamophobia, as it provides the dominant narratives that support the spread of xenophobic or discriminatory actions against Muslims. This relies in a historical construction of Islamophobia, as well as in the reaction to the different international events that have marked the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century. Both of these ideas, imbricated in the highly disputed concept of “clash of civilization” developed by Samuel Huntington, refers to a spread of Islamophobia as a result of the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the September 11 attacks or the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the late terrorist attacks committed by Daesh in American and European soil; although it can go back way further in time, to colonialism, the clashes of the Byzantine Empire against the Islamic Empire or the attacks by Ottoman boats in the Mediterranean.

The construction of the Spanish identity was intimately related, to the so-called Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslim sovereignty, which finished in 1492, and the construction of a homogeneously cultural and catholic identity for the country

This is especially relevant in Spain, where the construction of the Spanish identity was intimately related, to the so-called Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslim sovereignty, which finished in 1492, and the construction of a homogeneously cultural and catholic identity for the country (Martín Muñoz et al., 1998). As shown by different authors, this transcends the more physically obvious examples, such as the banishment of the Moriscos in 1609, and can be traced to the whole construction of the values of the population, as shown for example in the construction of the evil, funny or ridiculous, or untrustworthy Muslim through the Spanish literature of the 16th century on (Gómez Torres, 2005; González Alcantud, 2002). The result is the understanding of Islam as an essential element of cultural differentiation (Mateo Dieste, 1997), and the development of an Islamophobic imaginary among society, which portrays Islam and Muslims from a negative perspective and places them as an enemy of Western civilization.

The construction of counter-narratives

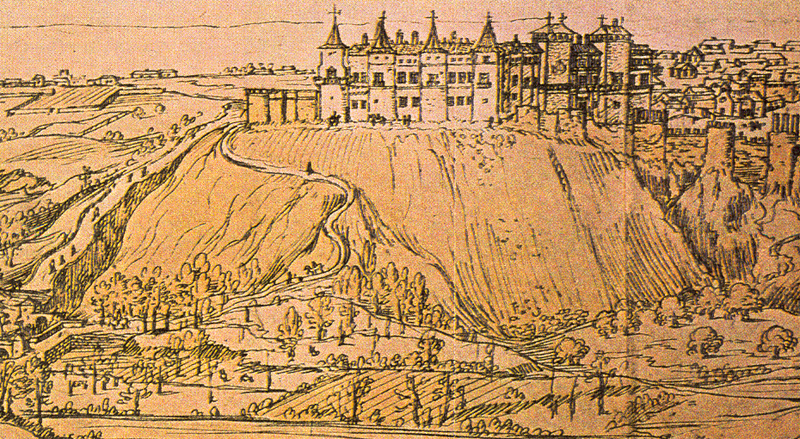

This cultural and historical root of Islamophobia in the country emphasizes the need of developing new counter-narratives, understood as the development of alternative discourses and counter-facts in order to revert the dominant narrative and power relations (Mora, 2014). In this sense, it is our goal to highlight the recent initiative launched by the Islamic Culture Foundation in the fight against Islamophobia, through the development of the Centre for the Study of the Islamic Madrid. This Centre was officially launched in 2017, with the goal of recovering the mostly-unknown cultural and material Islamic heritage of Madrid. Madrid is the only European capital of Islamic origin, having been found some time around the years 858-871 by the Emir Mohamed I, however, its origins are almost untraceable, both culturally and physically, as a result of its designation as capital of Spain in 1561, by king Felipe II. However, this projects attempts at going beyond its cultural goal, presenting itself as a useful tool for building bridges among civilizations, by blurring the lines of the dichotomy “us-them” created between Spanish nationals and Muslims and portraying a common heritage, and the emphasis of the historical and cultural ties shared.

In this sense, we can highlight a first attempt of emphasizing this common heritage through the promotion of a first European initiative, launched in the European Council under the Recommendation 1162 for the recognition of the contribution of the Islamic civilization to the European culture. The purpose underlying the initiative surpasses the mere recognition of its contribution, and tries to place its focus on the existence of a shared history and difficulty of identifying a clear line between the European and the Islamic or Arab culture.

The CEMI presents itself as a useful tool for building bridges among civilizations, by blurring the lines of the dichotomy “us-them” created between Spanish nationals and Muslims and portraying a common heritage

Among the different examples we would like to highlight, with regards to the historic re-reading initiatives carried out in Spain, we might begin with the article recently published by Daniel Gil-Benumeya, Scientific coordinator of the CEMI, in the newspaper 20 minutos. In this article, by relying on the history of the mathematician Maslama al-Mayriti, Gil-Benumeya explains the process of erasing of the Islamic traces of Madrid historically carried out (which allows us to understand, also, the population’s lack of knowledge of this superb scientist). As concluded in the article, his recognition would imply the acknowledgement of an Islamic component of our history and, thus, the inclusion of an Islamic element in the identity of those born in Madrid.

But, just as the article is interesting, we consider interesting the reactions it triggered, which can be read in the comments beneath the article. All of them link the topic at hand with a question of identity, highlighting two main ideas: the fact that it constitutes a part of our identity already rejected, and thus it no longer exists; and its identification as a threat to our current identity, by linking it to the notions of “sharia”, “terrorism”, “women rights” and “autocratic regimes”. Its justification relies on the predominance of a culture of the “Reconquista” (understood as a homogeneous catholic civilization) or in the existence of previous cultures, thus placing it as a historical parenthesis created by the Muslim invasion.

But, just as the article is interesting, we consider interesting the reactions it triggered, which can be read in the comments beneath the article. All of them link the topic at hand with a question of identity, highlighting two main ideas: the fact that it constitutes a part of our identity already rejected, and thus it no longer exists; and its identification as a threat to our current identity, by linking it to the notions of “sharia”, “terrorism”, “women rights” and “autocratic regimes”. Its justification relies on the predominance of a culture of the “Reconquista” (understood as a homogeneous catholic civilization) or in the existence of previous cultures, thus placing it as a historical parenthesis created by the Muslim invasion.

A dialectic fight on the country’s history

This initiative is not only a one-way direction, and in this sense we find a striking example in the naming and recognition of the “monumental complex Mosque-Cathedral” of Córdoba (as it is currently called). The controversy began with the registration of the monument by the Church as its property, alleging its ownership since 1236. Even though it was already managing its visits and maintenance, the official recognition of its ownership showed a change in attitude by the incumbents of the cathedral (Cabildo), the body in charge of its management. This has seen a gradual increase in the presence of catholic symbols, through the importation of catholic figures and statues, in the form of temporary exhibitions, a brief change of name in 2014 to the “Cathedral of Córdoba”, thus rejecting the Islamic past that so-importantly characterized the monument, the supervision of the touristic guides by the Church, or the social purpose of the monument. In this sense, the director of the Cabildo published a tweet on the objectives of the night visits organized in the Mosque-Cathedral, stating:

“The night visit is a privileged means to know the history and architecture of the Cathedral of Cordoba and has to be, as happens with the temple itself, a means for evangelization.”

This case has been highly contested by the citizen’s Platform Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba.

A third case, interesting to highlight, are the controversies surrounding the celebration of the conquest of Granada, which put an end to the Islamic rule of the Iberian Peninsula. This holiday, always polemic, hit the headlines last year when the politician Esperanza Aguirre, former president of the Community of Madrid, published a tweet on celebration of the day, in which she stated:

“Today, 525 years ago, was the conquest of Granada by the Catholic Kings. It is a day of glory for all Spanish women. With Islam we wouldn’t have any freedom”

Once again, our possible Muslim heritage is linked to a negative homogenization of Islam, and this to the lack of women rights. This tries to emphasize the negative situation in which we would be today if we were to embrace our Muslim heritage once again.

A polemic celebration in the city of Granada, this holiday commemorates the annexation of Granada to the kingdom of Castille and the imposition of the catholic religion among its population. Today, the holiday represents an opportunity for far-right movements to demonstrate against immigration and promote an image of a broken society.

This group relies on the British historian, Hobsbawn, to denounce a re-writing of History in order to legitimate today’s reality.

These demonstrations have been opposed by a wide sector of civil society and the media, among which the group “Granada abierta” plays an especially relevant role. This group relies on the British historian, Hobsbawn, to denounce a re-writing of History in order to legitimate today’s reality, or at least the interests of the ruling elites. In their opinion, this relies in two axes: a) the portrayal of the conquest of Granada as the moment of unification of Spain, when its territory was still, in reality, divided in kingdoms, and b) the hiding of the violation of the kingdom’s terms of rendition and the attack and process of erasing carried out against its culture, language and religion. The main goal underlying both of them is the portrayal of a culturally homogeneous country.

All this three cases, although not studied in depth, show an effort to reinterpret the country’s history and heritage, in what we can consider an attempt to define what is part of the countries’ identity and what is not part of it. At the bottom line, we witness an attempt to determine if Islam or the Muslim population should be understood as a historical defining part of our identity, and, thus, as an inherent part of today’s society or not.

All this three cases, although not studied in depth, show an effort to reinterpret the country’s history and heritage, in what we can consider an attempt to define what is part of the countries’ identity and what is not part of it. At the bottom line, we witness an attempt to determine if Islam or the Muslim population should be understood as a historical defining part of our identity, and, thus, as an inherent part of today’s society or not.

In this framework, the initiatives highlighted (including those launched by our Foundation) emphasize the need of a cultural approach to islamophobia in order to define the place of Muslims in society, as part of an inclusion/exclusion process.

Sources:

Aguilera-Carnerero, Carmen (2018). “Islamophobia in Spain: National Report 2017”, in Enes Bayrakli y Fared Hafez, European Islamophobia Report 2017. Istanbul: SETA.

Gómez Torres, David (2005). “La islamofobia de ayer y de hoy: la homogeneización de la imagen del moro en la comedia de Lope de Vega”, Espéculo. Revista de estudios literarios. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid

González Alcantud, José Antonio (2002). “Lo moro. Las lógicas de la derrota y la formación del estereotipo islámico”. Barcelona: Anthropos Editorial Del Hombre

Martín Muñoz, Gema, et al. (1998). El Islam y el mundo árabe. Guía didáctica para profesores y formadores. Madrid: AECID

Mateo Dieste, Josep Lluis (1997). “El ‘moro’ entre los primitivos. El caso del Protectorado español en Marruecos”. Barcelona: Fundación La Caixa

Mora, Raúl Alberto (2014). “Counter-Narrative”, Key Concepts in Intercultural Dialogue, nº 36. Available at: <https://centerforinterculturaldialogue.org>

No Comments