Assertions about the lack of reformist movements in Islam are sadly very common. This argument tends to portray Islam as a stagnant religion which fails to adequately deal with today’s issues and problems. However, many attempts of reform have been carried out. This article explores the way in which reformation has taken place within Islam, outlining the main lines of reform:

“We keep hearing calls for an ‘Islamic Reformation’, assumed to be the remedy for a fundamentalist Islam behind the conservative Salafi brand as well as the Jihadist. Islam, under these assumptions, generates problems because it had not been ‘reformed’. The assumed model is the Christian Reformation of the sixteenth century, the Protestant reformers, Luther, Calvin and their followers. Informed writers on religion and history have pointed out the problematic nature of these suppositions, with regard to the histories of both Christianity and Islam.

I argue here that Islam has undergone many reformations, in radically different directions: Wahhabism, much like Protestant reforms, urged a return to the scriptures and prophetic traditions and a rejection of ‘corrupt’ and heretical practices of saint worship and visitation of tombs, Sufi mysticism and ceremonies, and sectarian doctrines, principally Shi`ism. In contrast, a modernist and rationalist reformation was a powerful strand in public life, politics and culture from the nineteenth and throughout the twentieth centuries, in the Ottoman, Arab and Iranian worlds. These different kinds of ‘reform’ were institutionalised in various ways, recounted below. Liberal/ modernist reforms are now available in public space, but not attractive to most religious Muslims because they do not fit in with their social and psychological needs and outlooks.

The Protestant Reformation was not a liberal enterprise: it was the original ‘fundamentalism’, which is the derivation of the label ‘fundamentalism’ for Islam. The Christianity that was being ‘reformed’ was that of the Catholic Church, one that was based on Church authority and hierarchy. Worship is conducted through rituals and ceremonies celebrated by its priesthood, and claiming the authority to dispense salvation. The Reformation was to challenge these assertions of authority and uphold, instead, the authority of ‘the Word’, the Bible, literally interpreted and preached. The Word rather than the Church Fathers was the source of all authority and the individual believer was to read the Bible and follow it according to her conscience. Salvation was by divine grace and not by authoritative dispensation via a priest. As such, it dispensed with elaborate ritual and ceremony, images and tunes, considered as heretical (note the parallels with Salafi Islam), in favour of an austere preaching and worship, based on the literalism of reading the scriptures in the vernacular languages. Hellfire was the sanction against sin, and salvation was by seeking divine grace, and not by priestly dispensation. When Protestants ruled, as in Calvin’s Geneva or in the Lutheran principalities, they instituted stern punishments for sin and heresy.

Orthodox Islam

Perceptive commentators, notably the late Ernest Gellner, had long noted the parallels between Protestantism and orthodox Islam. Gellner postulated a mirror-image reverse symmetry on the two sides of the Mediterranean: Christian Europe featured an established church with bells and candles, elaborate ritual and ceremony, opulent church hierarchy, and generally audio-visual aids to worship; as against the austere and literal scripturalism of the dissident Protestants. On the other side, it was orthodox Islam which was literalist, scriptural, austere, as against the audio-visual worship and ritual of heterodox and mystic Islam, in the form of sectarian and Sufi outfits.

Perceptive commentators, notably the late Ernest Gellner, had long noted the parallels between Protestantism and orthodox Islam. Gellner postulated a mirror-image reverse symmetry on the two sides of the Mediterranean: Christian Europe featured an established church with bells and candles, elaborate ritual and ceremony, opulent church hierarchy, and generally audio-visual aids to worship; as against the austere and literal scripturalism of the dissident Protestants. On the other side, it was orthodox Islam which was literalist, scriptural, austere, as against the audio-visual worship and ritual of heterodox and mystic Islam, in the form of sectarian and Sufi outfits.

Most Islamic lands for much of their history and until recent times featured a diversity of Sufi orders, comprising large sections if not majorities of the population, high and low, with elite intellectual orders as well as popular Sufism for common people and soldiery.

Crucially, Sufi orders constituted modes of social organisation, superimposed on craft and trade guilds, military units, urban quarters and rural/tribal regions. Gellner noted, in relation to North Africa, how Sufi saintly dynasties acted as intermediaries and conciliators cutting across tribal units. Some of the major Sufi orders disposed of considerable wealth in the form of waqf endowments, and their leaders enjoyed considerable power and connection to the ruling military elites, particularly in the Mamluke dynasties in Egypt and Syria, but also under Ottoman rule at various points.

Being part of the power elite, Sufi ranks often included prominent ulama and judges, the guardians of orthodox Islam. This complicity excited periodic denunciation by occasional guardians of purity among the ulama, the most famous, or notorious, being Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328). He confronted rival ulama, including prominent judges who doubled as Sufi leaders, denouncing mystic practices, including ceremonies of music and dancing, as heretical. Equally, he fulminated against popular mysticism and magic, notably the visitation of tombs as saint worship, for contradicting the oneness of God, as shirk, the association of other deities with the one God. Ibn Taymiyya’s fortunes fluctuated in his confrontation with the Sufis, depending on the disposition of the current Mamluke ruler. He ended his days imprisoned after losing out to opponents. Paradoxically, his funeral and tomb were sought after by the populace for blessing. Ibn Taymiyya’s doctrines and polemics constitute the most influential canon on the doctrinal and legal underpinnings of the current Saudi state and its clerics. Similar episodes of forthright clerics attacking sectarian and Sufi heterodoxies occur at regular intervals throughout Muslim history, their fortunes fluctuating with the balance of forces and possible patronage from the powerful.

What is ‘reform’ in these contexts?

What is ‘reform’ in these contexts? It is the assertion of literalist orthodoxy against what was seen as heresy and innovation: that is, fundamentalism, parallel to the Protestant fundamentalists, but in vastly different contexts. And it was not one decisive ‘reformation’, but repeated cycles. Salafist and Jihadist trends in modern Islam, including Saudi Wahhabism and its spread, are part of that trend: hardly the ‘moderate’ and liberal reformation that is being sought. The Wahhabi movement and its establishment were certainly claimed as a reformation, islah, and was recognised as such in some quarters.

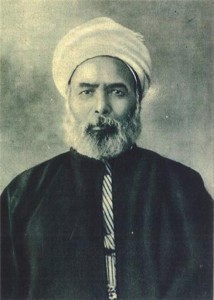

But there was another kind of reformation, starting in the nineteenth century, part of Ottoman reforms, the Arab nahda, renaissance, and the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1906. The innovations in doctrine and law were part of political and cultural modernity, aimed at making Islam compatible with the modern transformations in society, culture and politics. In the Ottoman reforms, law, while nominally encompassing the Shari`a, was codified as civil law and etatised as state law. The most influential formulations of renovated doctrines came from intellectual reformers, most notably the pan-Islamic Jamaleddin al-Afghani (1838-1897) and his disciple Muhammad Abdu (d. 1905) who became Grand Mufti of Egypt.

But there was another kind of reformation, starting in the nineteenth century, part of Ottoman reforms, the Arab nahda, renaissance, and the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1906. The innovations in doctrine and law were part of political and cultural modernity, aimed at making Islam compatible with the modern transformations in society, culture and politics. In the Ottoman reforms, law, while nominally encompassing the Shari`a, was codified as civil law and etatised as state law. The most influential formulations of renovated doctrines came from intellectual reformers, most notably the pan-Islamic Jamaleddin al-Afghani (1838-1897) and his disciple Muhammad Abdu (d. 1905) who became Grand Mufti of Egypt.

They were confronted by the imperial dominance of the European powers over the Islamic world, and like their secular nationalist counterparts, sought the remedy in the Islamic nations following the path that gave Europe its power: science and rationality, economic and military reforms and rational organisation of state and society. These steps were perfectly in harmony with Islam, they argued: not the corrupted Islam of recent history (as they saw it), but the pristine Islam of the Prophet and the first generation of Muslims. They read modern political concepts into Islamic origins: the Prophet commanded shura, consultation among the believers on the affairs of the community, and this was elemental democracy. The Caliph of the Muslims obtained his legitimacy from the bay`a, a pledge of allegiance from the members of the community, another element of conditional consent. Maslaha is the principle of public interest, according to which the sacred law was to be interpreted”.

By Sami Zubaida, Emeritus Professor of Politics and Sociology at Birkbeck, University of London.

No Comments