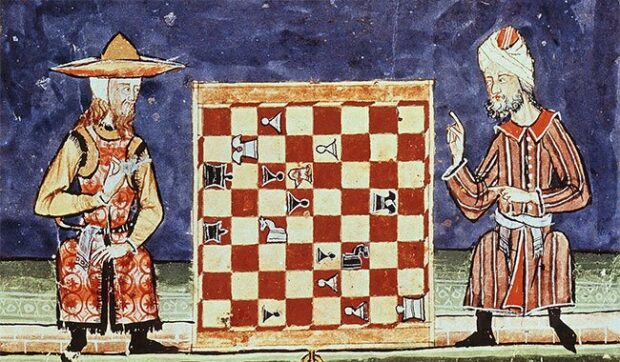

Chess and social diversity

Chess is an example of the Arab-Muslim world’s role as transmitter. Originating in India, the game arrived in Persia before spreading throughout the Arab-Muslim world after the conquest of the Sassanid Empire. It entered Europe, probably via Spain, and enjoyed dazzling success. The Book of Games (Libro de los juegos) was commissioned by Alfonso X, King of Castile (r. 1252-1284) and completed in the Toledo scriptorium in 1283. It contains around a hundred chess problems, which explains why the chessboard is visible. The players depicted reflect the great social and religious diversity of Spain’s population. Each group is distinguished by specific clothing.

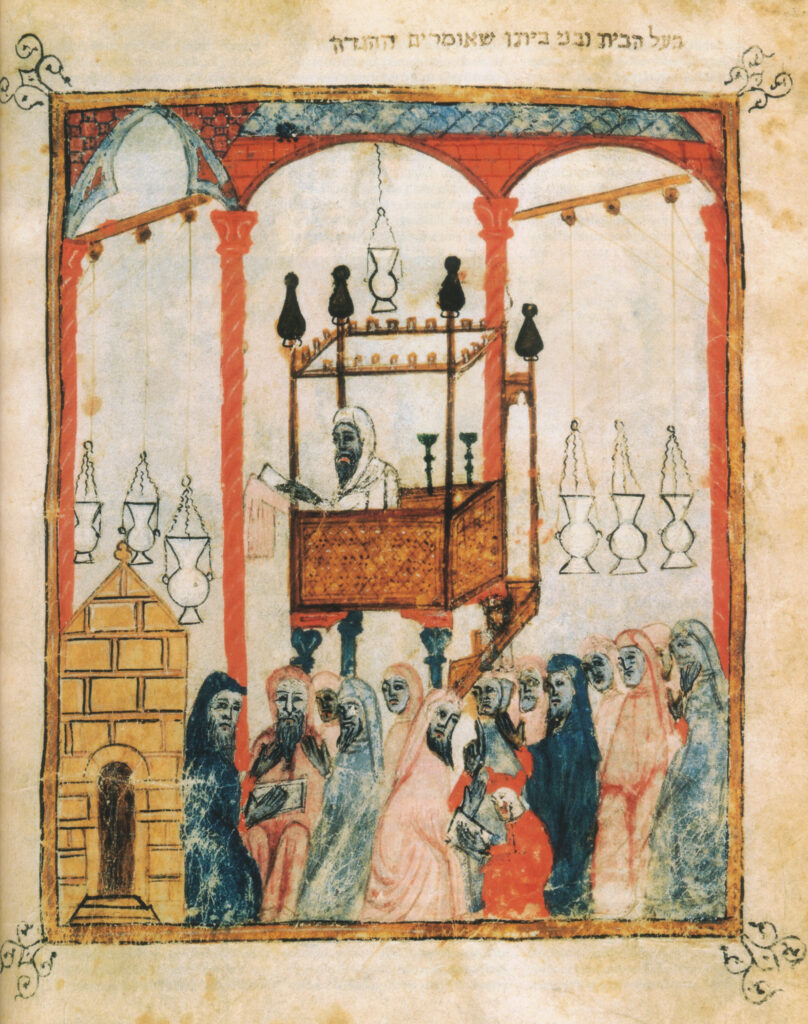

Averroes in dialogue with the Greek philosopher Porphyry

Ibn Rushd (1126-1198) was one of the greatest scholars of al-Andalus. He was the author of scientific works (mathematics, astronomy, medicine), as well as Islamic law. He was a qādī (judge) of Seville in 1160, and belonged to the Mâlikite school. He is best known for his philosophical work, in particular his important commentaries on Aristotle, which had a considerable influence in the West from the following century. He considered that philosophy was not incompatible with the teachings of Islam. In so doing, he exposed himself to criticism from the Ash’arite school, favored by the Almohad caliphs: this school rejected his approach as rationalist, which led to Ibn Rushd’s dismissal in 1197. His work, suspected of heresy, had no posterity in the Muslim world. However, it became accessible to Christianity via Jewish translators, who transcribed his name into Aben Roys, hence the Latin form Averroes. The image presented here below shows Averroes discussing (in Latin) with the Greek philosopher Porphyry of Tyre (c. 234 – c. 305). This depiction emphasizes his role as a link between ancient and medieval, Arab-Muslim and Western knowledge.

Discussion between Averroes and Porphyry, Monfredo de Monte Imperialis, Liber de herbis, 14th © Wikimedia Commons.

The image, taken from a 14th-century manuscript, is a reminder that religious minorities, and in particular the large Jewish community, enjoyed freedom of worship within the limits of the dhimma status. This tolerance allowed Jewish culture to flourish in Spain.

The mosque-cathedral of Cordoba

Cordoba’s Mosque-Cathedral is a fine example of how Christian and Muslim influences could be blended. In Visigothic times, it was a church dedicated to St. Vincent. After the Muslim conquest, the building was divided in two: one part was converted into a mosque, and the other was reserved for Christian worship. After settling in Spain, Abd al-Rahman I (r. 756-788) decided to build a mosque to rival those of the Abbasids. He bought out the Christian portion. Work began in 784. His successors enlarged the mosque, which was completed in 987. Note that the mihrab curiously faces south instead of Mecca. Cordoba was conquered by Castile in 1236. The center of the mosque was converted into a church, then a cathedral. In the 16th century, the Christians built a cathedral more in keeping with the canons of Catholic architecture, which seems to be embedded in the mosque.

Conviviality on the Iberian Peninsula

In the 8th century, Arab conquerors established themselves in Spain. Muslims, Jews and Christians lived together peacefully on the peninsula. In the mid-10th century, the Caliph of Cordoba celebrated the Christian feast of St. John with horse races; under Muslim rule, Toledo continued to have Catholic archbishops. In the 12th century, Maimonides, rabbi, philosopher and physician (1135-1204), was free to practice his art and publish his works in Cordoba, in the land of Islam [1].

On the other side of the border, around 875, the King of Leon sent his son, the future Ordono II, to complete his education with the Muslim emir of Saragossa. After the reconquest of Toledo in 1085, Alfonso VI (1042-1109), King of Castile, proclaimed himself “emperor of the two religions” (Christian and Muslim). Alfonso X (1252-1284) planned to open a joint university (medersa) for Christians, Muslims and Jews in Murcia. Even in the 13th century, Toledo was considered the Jerusalem of Spanish Jewry, with splendid synagogues that can be admired today under their Christian names of Santa Maria la Blanca and Nuestra Señora del Transito [2].

These few examples testify to the originality of the Iberian Peninsula, which from 711 (when the first Muslim contingents landed on its shores) to 1492 (when the Catholic Monarchs conquered Granada, capital of the last emirate), found itself politically and culturally divided between two civilizations: the Muslim East and the Christian West; at the crossroads of these two worlds, a Jewish minority managed to survive. The three religions of the Book would have lived, if not in harmony, at least in mutual respect, with Muslim or Christian rulers having the wisdom not to impose their faith by force. What exactly is the situation? Does medieval Spain deserve to go down in history as a model of tolerance and cultural pluralism? [3].

The invaders of the 8th century were, for the most part, Amazigh/Berbers who had barely become Islamized. The actual Arabs would have numbered between thirty and fifty thousand [4]. The bulk of the population only converted to Islam at a later date. This is because the conquerors, who were warriors in search of booty, did little religious proselytizing. They allowed the Jews to remain in Muslim territory, as well as large communities of Mozarabic Christians. The Christian Reconquest, on the other hand, was not an uninterrupted struggle [5].

It would also be a mistake to imagine that the Christians had a clear sense of purpose from the outset. The Visigothic monarchy, which had been established in Spain since the 6th century, had been swept away, its cadres destroyed or dispersed. It wasn’t until the second half of the 11th century that the battle of Covadonga (722), which halted the advance of the Moors into Asturias, and it became the symbol of resistance, the starting point of a great enterprise.

This resistance was part of a historical perspective: the reconstitution of the political unity of a peninsula liberated from the Moors, and this perspective was the work of Mozarabic monks who, fleeing al-Andalus, had found asylum in the kingdom of Asturias. It was here that the idea of Reconquest was born, i.e. the ambition to return the peninsula to those who considered themselves its rightful owners. This Reconquest was accompanied by a double population movement: the occupiers were expelled and replaced by settlers from the north. Only in exceptional cases were Muslims allowed to stay [6].

The three religious minorities – Christian, Jewish and Muslim – have always had a legal existence, whatever the dominant political regime in the peninsular states.

This is a fact of civilization peculiar to medieval Spain: the coexistence of social groups practicing different religions. In the land of Islam, the principle of dhimma (protection) made special provision for the “People of the Book”, Jews and Christians [7].

Nature of Convivencia

The Jews were the first to benefit from the provisions of Convivencia. Persecuted by the last Visigoth kings, they had rather welcomed the Muslim invaders and often made their task easier. The emirs (governors or military chiefs of provinces under Muslim rule) and caliphs (Muslim rulers, considered successors to the Prophet) readily used them in administration, finance and economic activities. As a result, Jewish communities flourished in al-Andalus until the 12th century.

This was a pivotal period for these communities: in the 12th century, fleeing persecution by the Almoravids and Almohads (intransigent fundamentalist dynasties from Morocco), [8] Jews emigrated to the Christian kingdoms. Many of them put their experience to work for the rulers, in finance and administration of the reconquered territories. Their legal status was similar to that which they had enjoyed in the 10th century, under the Caliphate of Cordoba: in exchange for often heavy taxes, they enjoyed administrative, religious and even legal autonomy, under the guidance of their rabbis.

The heyday of Judaism in Castile spanned two centuries, from the mid-12th to the mid-14th century. This prosperity came to an end with the recession and catastrophes that followed the Black Death, which broke out in Spain in 1348. The Christian masses, fanaticized by preachers, blamed the Jews for all their misfortunes. Popular anti-Semitism culminated in the massacres of 1391; [9] it would never cease to wreak havoc, and Jewish communities, impoverished by numerous more or less sincere conversions, declined sharply in the 15th century.

Like the Jews, the Mozarabs and Mudéjars were original religious minorities. Mozarabes and Mudéjars are protected by comparable legal statutes. In return, they were free to practice their religion and administer their own affairs.

Mozarabs are Christians living in Muslim territory, and Mudéjars are Muslim subjects of a Christian sovereign.

By the middle of the 8th century, large Mozarabic communities were being organized in Toledo, Cordoba, Seville, Mérida, etc., with their own civil administration (the counts, whose duties included tax collection) and ecclesiastical hierarchy. These communities had their own churches and monasteries. They retained their own liturgy: the Mozarabic rite, based on the Gothic rite instituted by Saint Isidore of Seville (570-636).

Over time, these Christians under Muslim domination came to arabize, as their etymology suggests: Mozarab comes from an Arabic word meaning “one who arabizes”. Latin remained their liturgical language, but they adopted Arabic as the language of culture and communication. The Mozarabs took Arabic names, and adopted Muslim clothing and lifestyles. In the 10th century, for example, they no longer ate pork and avoided accumulating images (paintings, sculptures) of God, the Virgin and the saints.

The reconquest of Toledo (1085) by Alfonso VI created a new situation. Thousands of Mozarabs were reintegrated into Christianity, not of their own free will, but as a result of a military victory. The Mozarabs of Toledo do not seem to have had any complaints about the Muslim authorities. They mingled with the Moors, rather than being confined to reserved quarters like the Jews. Many were indifferent to the political regime; some even left the city after the Reconquest and followed the Muslims in their flight.

Peculiarity of medieval Spain

This peculiarity of medieval Spain can be explained by the vicissitudes of history. Once the Reconquest was over, there was no longer any reason to maintain this state of affairs. That same year, 1492, the Catholic Monarchs recaptured Granada and expelled the Jews. Spain once again became a country like any other in European Christendom. This is regrettable, as Spain could and should have remained a bridge between East and West. Its rulers probably never thought of this. In 1492, they wanted to assimilate the defeated and the minority. They underestimated the scale of the task. The conversos, descendants of the Jews, sought to blend in with the masses, who suspected them of bad faith. The Moriscos, heirs of the Mudejars, refused to assimilate; they were expelled in the early 17th century [10].

Was there, at least, a constitution of an original culture born of reciprocal influences? Borrowings, to be sure, and in all fields: linguistic, literary, artistic…, but there was never just one dominant culture.

Of course, a Muslim Spaniard and a Christian Spaniard were no strangers to each other, but the former remained first and foremost a Muslim, the latter a Christian. This was clearly demonstrated by the Moriscos of the 16th century, who were very attached to the land of their ancestors, where they were at home in the same way as the “Old Christians”, but who lived in a world of their own: their language, their way of life, of dressing, of eating, of entertaining, as much or more than their religion, made them… foreigners in their homeland. The expulsion of 1609 [11] took note of this situation, with all the tragedies we know: banished from their homeland, Moriscos were often unwelcome in Islamic lands [12].

For a long time, and sometimes right up to the present day, Moriscos and Sephardim (Jews) have had an ambiguous attitude towards Spain: resentment against what they see as injustice and despoilment prevails, but it’s not hard to discern something resembling tenderness, nostalgia for a land that was once their ancestral home.

More than others, they have contributed to forging the image of an ideal medieval Spain, where three civilizations lived in harmony and harmony [13].

When it comes to literary history, things are less straightforward. Mozarabic lyricism is made up of poems in Arabic or Hebrew, mixed with words and even whole verses in Castilian. These texts sometimes take up songs that predate Muslim domination, and foreshadow Castilian Christmas carols (villancicos). This is why Menéndez Pidal [14] sees these compositions as the intermediate link between the Iberian music and poetry of classical antiquity and that of present-day Spain, but this is highly controversial ground.

The so-called aljamiada literature of the 14th century, [15] for its part, was invented by Mudejares or Jews who used Castilian and Arabic or Hebrew script. It’s Juan Ruiz, the archpriest of Hita (1290-1350), author of the “Libro de buen amor,” who has been the focus of controversy over Mudejarismo. Was Juan Ruiz as steeped in Muslim culture as has been claimed? He may have known, through translations, many of the oriental tales he includes in his poem in the form of apologues (little moral fables); however, borrowings from classical and western tradition are more important in his work than is generally believed [16].

There are two chronological stages: before and after the 12th century. Before, Christians and Jews lived more or less freely in al-Andalus. Afterwards, Muslims and Jews were allowed to remain in Christian Spain. Does this mean we can speak of a pluralist Spain? Certainly not. Jews and Mozarabs under Muslim rule, then Jews and Mudéjares under Christian rulers, had a “protected” status, with the pejorative nuance that attaches to this adjective.

Anna Akasoy believes that Convivencia in Muslim Spain was, undoubtedly, a fascinating life experience [17]:

“Historians of Europe often declare that Spain is “different.” This distinctiveness of the Iberian Peninsula has many faces and is frequently seen as rooted in its Islamic past. In the field of Islamic history, too, al-Andalus is somewhat different. It has its own specialists, research traditions, controversies, and trends. One of the salient features of historical studies of al-Andalus as well as of its popular image is the great interest in its interreligious dimension. In 2002, María Rosa Menocal published The Ornament of the World, one of the rare books on Islamic history written by an academic that enjoyed and still enjoys a tremendous popularity among nonspecialist readers. The book surveys intersections of Islamic, Jewish, and Christian elite culture, mostly in Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin literature and in architecture, from the Muslim conquest of the Iberian peninsula in 711 to the fall of Granada in 1492. Menocal presents the religious diversity commonly referred to as convivencia as one of the defining features of Andalusi intellectual and artistic productivity. She also argues that the narrow-minded forces that brought about its end were external, pointing to the Almoravids and Almohads from North Africa and Christians from north of the peninsula as responsible. The book’s subtitle, How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain, conjures the community of Abrahamic faiths. It reflects the optimism of those who identify in Andalusi history a model for a constructive relationship between “Islam” and “the West” that in the age of the “war on terror” many are desperate to find.’’

Convivencia: a fallacy?

In many ways, the 19th century can be considered the founding moment of modernity. It was a time of political, industrial and communications revolutions. As an offshoot of these transformations, Romantic sensibilities took hold of large segments of the European population, revolutionizing the way they perceived the world. The love of nature, the sea and the mountains took hold. The literate public, increasingly numerous, took a genuine interest in the typical and the folkloric, and felt the need to travel in order to rediscover themselves. It was at this point that Orientalism, a word coined in the 1830s, [18] was invented. Henceforth, Europe’s elites were looking for an area untouched by modernity, offering them the possibility of regenerating themselves in an entity considered to be a conservatory of archaisms, a dreamlike space conducive to escape from an overly corseted bourgeois society. It was precisely at this moment that the writings of François-René de Chateaubriand, Victor Hugo and Washington Irving established Spain as the “vestibule of the Orient,” or the “Orient of proximity [19].”

However, for Maya Soifer, Convivencia is a fallacy for many reasons, most importantly the fact that [20]:

“Postcolonial approaches address another major weakness that underlies Castro’s original formulation of convivencia: the absence of any consideration to the uneven distribution of power among the three religious communities. According to Thomas Glick’s insightful critique of Castro’s thought, in his vision, “relationships among persons of the three castes [i.e. Christians, Muslims, and Jews] were structured on a basis of parity, as if these groups were of equal demographic weights, political and military force, or cultural potency, and in complete disregard of the institutional or legal mechanisms controlling access to power.”’’

The great interest in Convivencia led part of the scientific community to take an interest in the country’s past, given that its Muslim past set it apart from the rest of Europe. From then on, the place and value accorded to this past never ceased to pose problems not only for Spanish society, but for Europe as a whole, insofar as the Iberian Peninsula was home to a multi-century Arab-Muslim presence. Indeed, the history of al-Andalus and its Arab-Muslim dynasties is unlikely to fit into the narrative of a Europe with Christian roots. As a result, the ways in which this past is apprehended are subject to diverse political recuperations. In fact, the spectrum is extremely wide, from the so-called “negationist” school (negacioncita) to those who believe that al-Andalus represents a civilizational apogee whose supposed tolerance prefigures the multiculturalism of our time, which would be characterized by the concept of Convivencia.

Though history establishes, through different written accounts, the existence of Convivencia in Muslim Spain. Yet, many Western intellectuals though they accept its existence yet they argue that it is exaggerated and blown out of proportion.

In this regard, Sarah-Mae Thomas writes [21]:

“So far the proposition has been that Convivencia was in fact a reality. However it will be argued here that perhaps to some extent it has been exaggerated. Much retrospective idealism was created through the historical accounts, the populism created by the Museum of Three Cultures in Cordoba and the mythos created by Washington Irving in the Tales of the Alhambra. Many contemporary historians purport that this retrospective utopianism of the Convivencia precariously masks the very presence of institutional fundamentalism in medieval Spain—both in its Jewish and Muslim manifestations in the nature of forced conversions, exile, lower standards of citizenship, higher taxation, and violence (Hillenbrand 1992, 7; Rothstein 2003, 9).”

While there were periods of tolerance and cultural exchange, the idea of a harmonious “golden age” is debated by historians. It is important to note that La Convivencia was not a utopian ideal, and there were also instances of conflict, persecution, and discrimination during its existence.

Is Convivencia a myth?

Though many Western historians support the idea of the existence of the Convivencia and the prevalence of the Spirit of Cordoba and see this as a concept to be copied and applied in modern times to allow conviviality between culture and creeds, yet others believe and argue that it is a historical myth. For them Convivencia never existed, Muslims used both Jews and Christians, given their knowledge, to advance their religious agenda: the prevalence and supremacy of the Islamic faith in Christian Europe.

One of the Western intellectuals who rejected Convivencia on the grounds that it is a gross myth is the Spanish academic and world-renowned Arabist Serafín Fanjul who has devoted his life to the study of Islam as a religious, sociological, economic and political phenomenon. His major works, of which the book entitled: “Al Andalus, l’invention d’un mythe,’’ [22] have caused quite a stir in Spain. His main focus is on al-Andalus, the medieval Spain of the three cultures, where the political domination of Islam enabled centuries of extraordinary cultural exchange between the Islamic, Christian and Jewish communities, against a backdrop of harmonious cohabitation.

However, Maya Soifer, in an article entitled: “Beyond convivencia: critical reflections on the historiography of interfaith relations in Christian Spain”, views Convivencia in the following way [23]:

“While Américo Castro’s convivencia remains an influential concept in medieval Iberian studies, its sway over the field has been lessening in recent years. Despite scholars’ best efforts to rethink and redefine the concept, it has resisted all attempts to transform it into a workable analytical tool. The article explores the malaise affecting convivencia, and suggests that the idea has become more of an impediment than a help to medieval Iberian studies. It argues that convivencia retains some of its former influence because scholars insist on understanding it as a distinctly Ibero‐Islamic phenomenon. However, this article suggests that the evidence for Islamic influence on interfaith coexistence in Christian Spain is scarce. Instead of continuing to embrace the nationalist myth of Spain’s unique status in medieval Europe, scholars need to acknowledge the basic similarities in the Christian treatment of religious minorities north and south of the Pyrenees. The article also explores other aspects of convivencia’s problematic legacy: polarization of the field between “tolerance” and “persecution,” and the inattention to the nuances of social and political power relations that affected Jewish–Christian–Muslim coexistence in Christian Iberia.’’

She shows how the imaginary world of the Romantics came to dominate, leaving behind a vision of the Hispanic past that is more fantasy than reality. Historical truth has been swept away by belief, and belief is all the more seductive in that the sirens of conformism have been able to hijack it to their own advantage, turning the Spain of the time into a veritable lost paradise of European multiculturalism.

Faced, with sterile biases and commonplaces of all kinds, Serafín Fanjul sets out to dispel the fog and “rediscover Spain”. And the historical reality his work restores is that of a peninsula where intolerance and conflict, suffering and violence reigned between communities, a far cry from the openness and appeasement too often upheld. Fanjul’s argumentation allows the reader to glimpse, contrary to the usual representation, a Spain that found in the Reconquista the path to emancipation and liberation and dispels Convivencia as a total myth [24].

In today’s Europe, faced with continuing Muslim immigration, we like to refer to the model of peaceful cohabitation of the three cultures of Al-Andalus. The history of Muslim Hispania or al-Andalus is thus an archetypal issue.

In the Middle Ages, the Iberian Peninsula witnessed a remarkable and unusual peaceful cohabitation between Jews, Christians and Muslims. This admirable cultural symbiosis lasted from the 8th century until the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, and even until the expulsion of the Moriscos in 1609.

Serafín Fanjul argues that, in reality, it was “a regime very similar to South African apartheid” and a “terrifying” era overall. Emphasizing that the motives and factors of struggle and confrontation between Muslim and Christian Spain were predominant throughout the period in question, he shows that al-Andalus was anything but a model of tolerance.

However, Alejandro Garcia Sanjuan destroys Serafin Panjul’s arguments one by one [25]:

“From S. Fanjul’s point of view, the so-called “myth of al-Andalus” represents a serious falsification of historical knowledge that requires rectification. Indeed, while it must be admitted that, like any other historical reality, the existence of al-Andalus has been subject to distortions and exaggerations, it is no less true that the supposed “myth” turns out to be far less important than it is. In reality, this myth is nothing more than an excuse to re-actualize the old ideas associated with conservative mythology and articulated around the classic notion of Reconquista.”

He goes on to say:

“Thus, the demolition of the so-called myth, in reality a mere “straw man”, constitutes the perfect excuse that justifies S. Fanjul’s true objective, the reshaping of conservative discourse and, ultimately, the legitimization of the notion of Reconquista which represents, in reality, the only real and authentic myth of medieval peninsular history.”

To conclude:

“In short, S. Fanjul’s work faithfully represents a historiographical trend that is directly linked to the current international rise of fascism, one of whose characteristics is the identification of Islam and Muslims as the great enemy of the West, seen as the spiritual reserve of humanity.’’

The Convivencia debate

Convivencia, the term often used to describe the coexistence of Christians, Muslims, and Jews in medieval Spain, has been debated among historians. Some suggest that it may be more of a myth than a reality, as noted in scholarly articles that argue it has become an impediment rather than a helpful concept in understanding social dynamics of the time. The distinctiveness of the Iberian Peninsula, and various interpretations, complicate the narrative around Convivencia.

The concept of Convivencia has been the subject of much scholarly debate.

While some view it as a golden age of religious and cultural tolerance, others argue that this characterization oversimplifies and idealizes the complex historical realities of medieval Spain.

Here are some arguments from both perspectives:

Arguments Supporting Convivencia as Historical Reality

- Cultural and Intellectual Exchange: There is significant evidence of cultural and intellectual exchange among Muslims, Christians, and Jews during this period. The translation movements in cities like Toledo, where scholars translated works from Arabic into Latin and Hebrew, are often cited as examples of this coexistence and cooperation.

- Philosophical Dialogue: Scholars from different religious backgrounds engaged in philosophical and theological debates, enriching each other’s traditions and contributing to a vibrant intellectual culture.

- Economic Collaboration: Various historical records indicate that Muslims, Christians, and Jews engaged in trade and commerce together, contributing to the economic prosperity of the region.

- Architectural and Artistic Achievements, Unique Blend of Styles: The period saw the creation of architectural masterpieces like the Alhambra, the Great Mosque of Córdoba, and the Synagogue of El Transito, which reflect a blend of Islamic, Christian, and Jewish artistic traditions.

- Periods of Relative Peace: There were periods during which the three religious communities lived relatively peacefully under Muslim rule, especially when compared to the periods of intense conflict that followed, such as the Reconquista and the Inquisition.

- Legal Frameworks for Coexistence, Dhimmis: Under Muslim rule, Christians and Jews were given the status of dhimmis, which allowed them to practice their religion and maintain their own legal systems in exchange for paying a tax (jizyah). This legal framework provided a degree of protection and autonomy for non-Muslims.

Arguments Challenging the Myth of Convivencia

- Instances of Conflict: Critics point out that there were significant episodes of violence and persecution during this period. For example, there were anti-Jewish pogroms in Christian-ruled territories and instances of forced conversions and expulsions.

- Legal and Social Inequality: Non-Muslims under Muslim rule were often subject to discriminatory laws and social practices. Dhimmis had to pay a special tax (jizyah) and were subject to certain legal restrictions.

- Romanticization and Anachronism: Some scholars argue that the concept of Convivencia is a romanticized and anachronistic interpretation, influenced by modern ideals of multiculturalism and tolerance. They suggest that the interactions among religious communities were more pragmatic and utilitarian than genuinely harmonious.

- Political Instrumentalization: The idea of Convivencia has sometimes been used for political purposes, both in the past and in contemporary contexts, to promote certain narratives of national identity or intercultural dialogue.

- Second-Class Citizenship: Despite being allowed to practice their religion, non-Muslims were often treated as second-class citizens and faced various forms of social and legal discrimination.

- Episodes of Violence and Persecution:

- Pogroms and Expulsions: There were significant episodes of violence, such as anti-Jewish pogroms in Christian territories and the eventual expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Spain in the late 15th

- Forced Conversions: There were instances of forced conversions and religious persecution, especially during the periods of heightened tension and conflict.

While the Convivencia period did witness moments of cultural and intellectual flourishing and cooperation among Muslims, Christians, and Jews, it was also marked by significant tensions, conflicts, and inequalities. The reality of this historical period is more complex than the idealized notion of Convivencia suggests. Scholarly consensus tends to acknowledge both the positive and negative aspects, recognizing that while there were notable instances of coexistence and collaboration, these were often accompanied by underlying social, political, and religious tensions [26].

The period of Convivencia in medieval Spain is marked by both notable achievements and significant challenges. While it provided a framework for cultural and intellectual exchange and contributed to the region’s economic and artistic development, it was also characterized by social inequalities, episodes of violence, and underlying tensions between different religious communities. Understanding both the pros and cons of this period allows for a more nuanced appreciation of its historical significance.

Conclusion: A time of nostalgy

Convivencia in Al-Andalus refers to the coexistence of different cultures, religions, and ethnicities during the period of Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula (711-1492). While often romanticized as a model of tolerance and harmonious interaction, the reality was more complex. There were periods of relative peace and cultural exchange, but also significant tensions and outbreaks of violence. It is important to remember that Convivencia was a complex and evolving reality, not a static ideal [27].

The concept of Convivencia, common to the Castilian, Catalan, Portuguese and Occitan cultures, has been taken up by Occitan associations since the 1980s, and is now attracting growing interest from the general public and institutions alike.

Faced with the rise of negationists of all kinds, with religious or secular totalitarianism aimed at rejecting all otherness, and with the prevailing of declinists, La Convivencia intends to help rebuild world society.

But where does this concept come from? From what corners of history? What is its relevance to contemporary society? What cultural and social practices is it based on? What does La Convivencia say that goes beyond tolerance and secularism? Is there a pedagogy of La Convivencia?

Thanks to Convivencia, the most extraordinary meeting of the Middle Ages took place: the meeting between East and West. Toledo, barbarian under the Visigoths, then under Muslim, Jewish and Christian rule, was the ideal setting for the encounter between the sciences of the Greeks gathered by al-Andalus – mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, medicine, geography – “sciences of the Ancients”, as the Arabs called them, and Judeo-Christian thought [28].

We can mention two such enlightened and “convivial” monarchs, the Caliph Abd al-Rahman III (891-961) and King Alfonso X el Sabio (1221-1284), as well as the anonymous authors of the Romancero, the poetic heritage of the Spanish people, born in the times of conviviality, which has, with great empathy, preserved the lament of Andalusian princes so delicate in their love of country. We can evoke celebrities: Averroes and Maimonides, of course, but also Ibn Hazm, author of ‘’The Dove’s Necklace,’’ the Moorish link in the chain that runs from Seneca to Unamuno [29].

In 1995, in Rome, John Paul II, in his call for dialogue and peace, [30] had twice advocated “’una convivenza’ between peoples and fractions of the same people” [31]. French press correspondents had trouble translating the concept. They had to use, without conviction, the word convivialité. The Académie Française was asked to find a more appropriate French equivalent. In the spring of 2004, it included “convivance” in the 9th edition of its dictionary.[32]

La Convivencia! This was what it took for a great mystic to emerge from Murcia in the 12th century: Ibn Arabi (1165- 1240), whom Dante remembered when writing his “Divine Comedy”. Disregarding all divisions, Ibn Arabi succeeded in reaching the true faith, ecumenism in the absolute sense, that which excommunicates no one. Witness these famous verses, the expression of a heart that professes the religion of love and welcomes in the same fervor the brotherhood of the three monotheisms as well as that of idolaters:

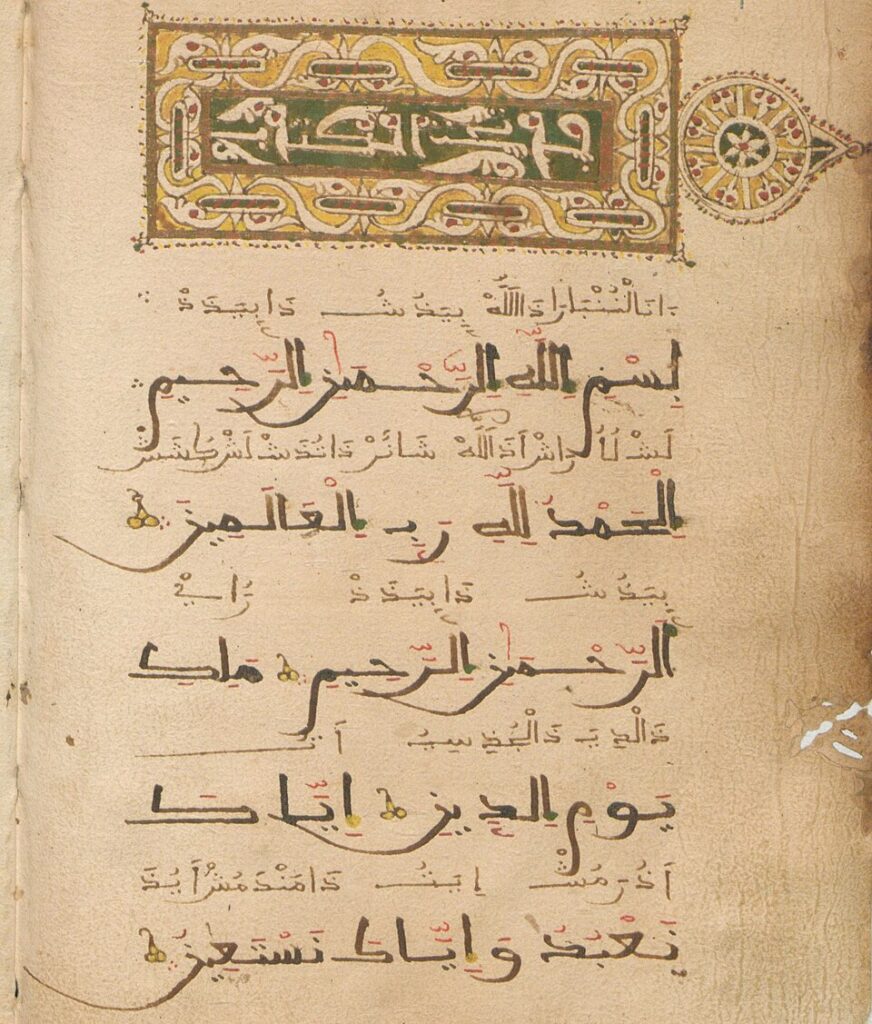

لقد صارَ قلبي قابِلا كُلَّ صورةٍ فمرعًى لغزلانٍ وَديْرٌ لرُهبانِ

وبيتٌ لِأَوثانٍ وكعبةُ طائفٍ وألواحُ توراةٍ ومصحفُ قُرآنِ

أَدينُ بدينِ الحُبِّ أَنّى َتَوجَّهَتْ ركائِبُهُ فالحُبُّ ديني وَإِيماني

My heart is now open to every image,

It is for the gazelle a pasture and for the monk, a hermitage.

Pagan temple, Kaaba, for circumambulation,

Tables of the Law, a book of the Koran.

I profess love, beyond its convoys,

For love, to all winds, is my worship and my faith [33].

The French historian Charles Sallefranque reminds us [34]:

“The Arab nobles quickly became Hispanic. Coming without their wives […], they followed the example of their first emir ‘Abd al-‘Azîz, who married Egilona […] At the end of the three or four generations resulting from these mixed unions, they were physically little different from their tributaries. Ribera goes so far as to say that the Umayyads are the most authentically Spanish of the Iberian dynasties. They were certainly more Spanish – after two centuries of intermarriage in the country – than the Habsburgs or the Bourbons.”

For some modern Western critics, even if Convivencia existed in Islamic Spain, yet the benevolence of al-Andalus towards religious minorities has been idealized. They were constantly discriminated against, even persecuted. It was the Almoravids (1056-1147), then the Almohads (1130-1269) from the Maghreb who dealt the fatal blow to the Spain of the “three religions”. The religious rigorism of the former contrasted with the eclecticism and freedom of life they found in Spain; they imposed the exclusive use of Arabic and sought to restore dogma to its original purity. The Almohads took over. These were Amazigh/Berbers whose name meant “followers of the one God”. They too were uncompromising about the purity of their faith and the obligations it entailed [35].

For Joseph Pérez, the conviviality never existed in Muslim Spain [36]:

“The myth of a Muslim Spain welcoming and benevolent towards religious minorities must be abandoned. The country’s masters have always been convinced of the superiority of their faith. Jews and Mozarabs were never more than second-class subjects. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the situation was reversed. Christianity would then become the dominant religion, and the rulers would agree to rule over infidels – Muslims this time, and still Jews – who would be tolerated, but subjected to discrimination of all kinds. And there’s one sure sign: sexual relations between Christians, Jews and Muslims were frequent, even though they were theoretically forbidden; on the other hand, there are no known cases of mixed marriages: there couldn’t have been any.”

However, these critics forget that al-Andalus saw the apogee of the Jewish culture the emergence of such great thinkers and philosophers such as Maimonides and Averroes and that while Western Europe was deep in conflicts, poverty and autocracy, Muslim Spain saw a real scientific and cultural development that was the main affluent that fed into and kick-started European Renaissance [37].

The origin of the Renaissance was the result of several factors. The Crusades were an abject failure militarily. On the other hand, the desire for the spices and other goods the Crusaders found in the east helped spur the Commercial Revolution which trade caused European countries to create the fertile ground for a rebirth of a more organized society. The humanists, whose writings, encouraged the intellectual climate of the Renaissance, based their ideas on the rediscovered Greek and Roman writing which Islamic Civilization preserved. Contact between Muslims and Christians occurred in Spain and Italy. One example would be Averroes, an Amazigh/Berber intellectual in Spain. His writing on Aristotle was translated and became the basis for “Acquinas Summa Theologica’’, written in late Middle Ages, was the beginning of intellectual rebirth [38].

In this regard Safvet Halilović writes [39]:

“However, there is no doubt that the Muslims had very much so participated in the development of world civilization, thanks to the efforts of outstanding figures in different branches of learning. Today, in the libraries throughout the world we can find thousands of documents that will testify to the efforts and achievements of Arabic-Islamic civilization in the fields of astronomy, mathematics, physics, chemistry, medicine, pharmacology, geography, architecture and other branches of science”.

Convivencia has become a universal reference regarding the Middle Ages in Spain. The distant origin of this reference point can be found in the ideas of the Spanish philologist Américo Castro, but it has also been reworked to become a tool with which to meet the multicultural challenges that have arisen in societies since the last quarter of the 20th century. Therefore, Convivencia is a political and not historical concept. This contraposition between political and historical concepts raises a broader and more complex discussion of historical knowledge and its relevance in contemporary societies.

Today, nevertheless, it’s safe to say that many people practice yesterday’s Convivencia without even knowing it [40].

Al-Andalus – the Iberian Peninsula (present-day Spain and Portugal) under Muslim rule from 711 to 1492, with wide geographical variations – left an indelible mark on human history. It was a time when the three monotheistic religions met in peace for a fairly long period of time, enabling all of them – Muslims, Jews and Christians – to experience a general flourishing that extended to all areas of life and culture. Some scholars refer to this flourishing period as the “Spirit of Cordoba”.

It is precisely this spirit that humanity needs today if it is to continue to live and think about a serene future, especially in these times when we feel that explosive tensions and racial and religious hatreds are resurfacing, even though we are supposed to be evolving in a time of encounters with others and easy communication [41].

Knowledge of the past, and the maintenance of this knowledge, are essential to building the future of humanity. We have seen that culture, science in all its forms and general flourishing were only able to reach such a degree – which would still be hard to imagine today – in 10th-century al-Andalus when the “Spirit of Cordoba”, instilled by a governor as brilliant as ‘Abd Arrahman an-Nassir, was able to give different ethnic and religious communities the opportunity to live and work with respect for each other. To build for the common good.

If we want to build such a beautiful and glorious future, we must rediscover this “Spirit of Cordoba” and nurture it for as long as possible. Amen.

Mohamed Chtatou

Foto de portada: A jew and a muslim playing chess, 1282. © Lavie.

Chronological landmarks:

711: Muslim invasion. Battle of Ctiadalete. End of Visigothic monarchy.

718: Pelayo, King of Asturias. Battle of Covadonga (traditional date; in fail between 721 and 725).

732: Charles Martel stops the Muslims at Poitiers.

755: ‘Ahd el-Rahman I proclaims himself Emir of Cordoba.

786: construction of the Cordoba Mosque begins.

791: Oviedo, capital of the Kingdom of Asturias.

801: Reconquest of Barcelona.

822: ‘Abd el-Rahman II, Emir of Cordoba.

859: martyrdom of Saint Fuloge in Cordoba.

885-888: Reconquest of Burgos and Zamora.

912: ‘Abd el-Rahman III. emir of Cordoba.

929: ‘Abd el-Rahman III proclaims himself caliph of Cordoba.

978: Almansour, first minister of the Cordoba caliphate.

1031: Disappearance of the Caliphate of Cordoba, Kingdoms of Taifas.

1064: Reconquest of Coimbra.

1085: Reconquest of Toledo.

1086: Almoravid invasion. 1094: Cid occupies Valencia.

1102: Almoravids recapture Valencia.

1118: Reconquest of Saragossa.

1143: End of Almoravid power. Return to the Taifas.

1156: Almohad invasion.

1212: Christian victory at Navas de Tolosa.

1229: Reconquest of Majorca.

1230: Reconquest of Mérida and Badajoz.

1236: Reconquest of Cordoba.

1238: Foundation of the Nasrid dynasty in Granada.

1246: Reconquest of Jaén.

1248: Reconquest of Seville.

1309: Reconquest of Gibraltar.

1474: Accession of Isabella the Catholic, Queen of Castile.

1478: Establishment of the Inquisition.

1481: Reconquest resumed: Granada War.

1492: Reconquest of Granada. Expulsion of the Jews.

References

[1] Sachedina, Abdulaziz. (2001). Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism. New York, US: Oxford University Press.

[2] Soifer, M. (2009). Beyond convivencia: critical reflections on the historiography of interfaith relations in Christian Spain. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies, 1(1), 19-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/17546550802700335

[3] Gampel, Benjamin R. (1992). Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Medieval Iberia: Convivencia Through the Eyes of Sephardic Jews. In Vivian B. Mann, Thomas F. Glick, & Jerrilynn D. Dodds (Eds.) Convivencia: Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain (pp. 11–37). New York, US: George Braziller Incorporated.

[4] Chtatou, Mohamed. (2022). Les Imazighen en al-Andalous. Le Monde Amazigh. Retrieved from https://amadalamazigh.press.ma/fr/les-imazighen-en-al-andalous/

[5] Viguera, Molins M.J. (2001). La identidad de al-Andalus. In Valdeón, Baruque J. (Ed), Año mil, año dos mil. Dos milenios en la historia de España (p. 183-204). Madrid, Spain: Sociedad Estatal España Nuevo Milenio.

[6] Meyerson, M. (ed.). (1999). Christians, Muslims, and Jews in Medieval and Early Modern Spain: Interaction and Cultural Change. Notre Dame, IN, US University of Notre Dame Press.

[7] Lowney, C. (2005). A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Medieval Spain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

[8] The Almoravids were a fundamentalist religious movement born in Kairouan in the early 11th century. They set up their capital in Marrakech in 1068 and quickly took control of Morocco. After the fall of Toledo (1085), the king of Seville called on them for help, and they rebuilt the unity of Muslim Spain for their own benefit, before returning to Africa in the early years of the 12th century. The Almohads were also rigorist Muslims (the word means followers of the one God). They began by creating a small state south of Marrakech (1124) and supplanted the Almoravids. From 1147 to 1150, they in turn reunified Muslim Spain. They returned to Morocco after their defeat at Las Navas de Tolosa (1212).

[9] Lea, H. C. (1896). Ferrand Martinez and the Massacres of 1391. The American Historical Review, 1(2), 209-219. https://doi.org/10.2307/1833647

In 1391, a wave of anti-Jewish riots swept through Christian Spain, leaving thousands dead and leading many thousands more to accept Christianity (sometimes by force) or to flee the country. As a result, the Church became increasingly suspicious of the sincerity of these former Jews’ conversions, which were then duly investigated by the Inquisition. Ecclesiastical authorities were particularly exercised about the possible influence of Spain’s large Jewish population on their former coreligionists, a concern that eventually led to the expulsion of the remaining Jews in 1492.

[10] Valdeón, Baruque J. (Ed.). (2004). Cristianos, Musulmanes y Judíos en la España Medieval : de la aceptación al rechazo. Valladolid, Spain : Ámbito et Fundación Duques de Soria.

[11] The expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain (Spanish: Expulsión de los moriscos, Catalan: Expulsió dels moriscos) was an expulsion promulgated by King Philip III of Spain on April 9, 1609, signifying the abandonment of Spanish territories by the Moriscos, descendants of Muslim populations converted to Christianity by the “Catholic Kings” decree of February 12, 1502. Although the Morisco rebellion in Granada (1568-1571) a few decades earlier was at the root of the decision, it particularly affected the Kingdom of Valencia, which lost a large proportion of its inhabitants.

Cf. Sánchez-Blanco, Rafael Benítez. (2001). Heroicas decisiones. La Monarquía católica y los moriscos valencianos. Valence, Spain : éd. Institut Alfons El Magnànim.

[12] Collins, R. & Goodman, A. (2002). Medieval Spain: Culture, Conflict and Coexistence. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

[13] Monroe, J. T. (1976). The Hispanic-Arabic World. In JR Barcia (ed.), Américo Castro and the Meaning of Spanish Civilization (pp. 69–87). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

[14] Menéndez Pidal, Ramón. (1968). España, eslabón entre la cristiandad y el islam (p. 17). Madrid, Spain : Espasa-Calpe, col. Austral nº 1280.

[15] López-Morillas, C., & Vázquez, M. A. (1994). ALJAMIADO LITERATURE. The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies, 56, 337-341. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25832605

[16] Vernet, J. (1985). Ce que la culture doit aux Arabes d’Espagne. Paris, France : Sindbad.

[17] Akasoy, Anna. (2010). CONVIVENCIA AND ITS DISCONTENTS: INTERFAITH LIFE IN AL-ANDALUS.

International Journal of Middle East Studies, 42(3), 489-499. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743810000516

[18] Orientalism refers to the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world by Western writers and artists. The term was significantly shaped by Edward Said in his 1978 work, which critiqued Western representations of the East and laid the foundation for postcolonial studies. The concept emerged prominently in the 1830s, marking a period when scholars and writers began to explore Eastern cultures, often portraying them through a colonial lens.

Cf. Said, Edward. (1979). Orientalism. New York, US: Vintage Books.

[19] Soifer, Maya. (2009). Op. cit.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Thomas, Sarah-Mae. (2013). The Convivencia in Islamic Spain. The Fountain Magazine. Retrieved from https://fountainmagazine.com/all-issues/2013/issue-94-july-august-2013/the-convivencia-july-2013

[22] Fanjul, Serafin. (2019). Al Andalus, l’invention d’un mythe. La réalité historique de l’Espagne des trois cultures. Paris, France : L’Artilleur.

[23] Soifer, Maya. (2009). Op. cit.

[24] García-Sanjuán, Alejandro. (2019). Denying the Islamic conquest of Iberia: A historiographical fraud. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies, 11. DOI: 10.1080/17546559.2019.1601753

[25] García-Sanjuán, Alejandro. (2018). Serafín Fanjul, Al-Andalus, l’invention d’un mythe. La réalité historique de l’Espagne des trois cultures. Cahiers de civilisation médiévale, 243. Retrieved from http://journals.openedition.org/ccm/4733; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ccm.4733

[26] Glick, Thomas F. (1979). Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages (p. 281). Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press. However, he seems to have warmed to the term or at least come to accept it by 1992, writing, “Convivencia survives. What we add to it is the admission that cultural interaction inevitably reflects a concrete and very complex social dynamic. What we retain of it is the understanding that acculturation implies a process of internalization of the ‘other’ that is the mechanism by which we make foreign cultural traits our own.” Glick, Thomas F. (1992). Convivencia: An Introductory Note. In Vivian B. Mann, Thomas F. Glick, & Jerrilynn D. Dodds (Eds.) Convivencia: Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain (p. 7). New York, NY, US: George Braziller, Inc.

[27] Gampel, Benjamin R. (1992). Op. cit.

[28] Montáves, Pedro Martinez. (2011). Significado y simbolo de Al-Andalus (p. 55). Granada, Spain: CantArabia Editorial, Caja Granada.

[29] Chejne, Anwar G. (1974). Muslim Spain: Its History and Culture. Minneapolis, MN, US : University of Minnesota Press.

[30] Szulc, Tadeusz (2007). Pope John Paul II: The Biography. London, UK : Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group.

[31] John Paul II. (1995). ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS JOHN PAUL II. L’Osservatore Romano. Weekly Edition in English, 41, 8-10. Retrieved from https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/speeches/1995/october/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_05101995_address-to-uno.html

[32] Convivance n. f. XVIIIe siècle, au sens de « fait de vivre ensemble ». Dérivé de l’ancien français convivre, « vivre ensemble », avec influence, au XXe siècle, de l’espagnol Convivencia. Situation dans laquelle des communautés, des groupes humains différents vivent ensemble au sein d’une même société en entretenant des relations de voisinage, de concorde et d’échange. La convivance des musulmans, des juifs et des chrétiens en Espagne prit fin en 1492.

[33] Arabi, Mohyiddîn b. (1966). Turjumân al-Ashwâq (l‘Interprète des ardents désirs) (p. 43). Beyrouth, Liban : éd. Dar Sader, Beyrouth.

[34] Sallefranque, Charles. (1954). Quand le soleil se levait à l’Occident. Cahiers du Sud, 326, 104.

[35] Chtatou, Mohamed. (2021). Al-Andalus: Multiculturalism, Tolerance and Convivencia. FUNCI. Retrieved from https://funci.org/al-andalus-multiculturalism-tolerance-and-convivencia/?lang=en

[36] Pérez, Joseph. (2017).

[37] Thorne, K. (2013). Diversity and coexistence: towards a convivencia for 21st century public administration. Public Administration Quarterly, 37(3),491+ . https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A359213174/AONE?u=anon~5ddddc8a&sid=googleScholar&xid=97847729

[38] The Summa Theologica is a famous work of theology by Saint Thomas Aquinas, often referred to simply as the Summa. It is a comprehensive overview of Christian doctrine, organized systematically and presented in a question-and-answer format.

The Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Aquinas’ brilliant synthesis of Christian thought, has had a decisive and permanent impact on philosophy and religion since the thirteenth century. As the title indicates, is a summing up of all that can be known about God and humanity’s relations with God. Divided into three parts, the work consists of 38 tracts, 631 questions, about 3000 articles, 10,000 objections and their answers.

Cf. Aquinas, Saint Thomas. (1948). Summa Theologica. Notre Dame, Indiana, US: Ave Maria Press.

[39] Halilović, Safvet. (2017). Op. cit., p. 69.

[40] Wood, Chris. (2010). Convivencia: a medieval idea with contemporary relevance. Journal Gold, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.25602/GOLD.atol.v1i1.218

[41] Moreno, E. M., & Roe, J. (2023). The Court of the Caliphate of al-Andalus: Four Years in Umayyad Córdoba. Edinburgh, UK : Edinburgh University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/jj.1011776

No Comments