In the present essay we will take a look at the initial position of women in Islam, how their situation has evolved over the last decades and what the future holds for Islamic feminism, starting with something as seemingly innocent as an Algerian song from the 1990s.

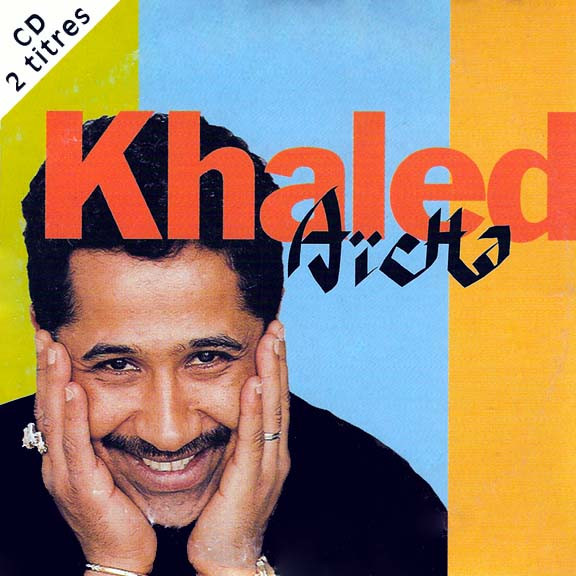

What phenomenon was brewing in the Maghreb in the 1990s that inspired Cheb Khaled to compose “Aicha”? Probably Khaled, like many other Maghrebis, was infected by the spirit of liberation that was beginning to spread among his compatriots and in which many young people participated, the liberation and emancipation of women in Islamic countries; the rise of an Islamic feminism that saw the light of day in the 1920s, and which was beginning to permeate Maghreb society.

Criticizes the social construct in which he grew up and the role of men as executioners in their relationship with women.

As the last stanza of “Aicha” relates, she does not want gold or jewels, “des barreaux sont des barreaux, même en or. Je veux les mêmes droits que toi. Du respect pour chaque jour ” [Bars are bars even if they are made of gold. I want the same rights as you. Respect for every day].

Cheb Khaled, a reference of Rai music[1], criticizes the social construct in which he grew up and the role of men as executioners in their relationship with women. Aicha is, on this occasion, a figurative woman, but her name could perfectly be a symbol. Not only because of the number of women (Muslim and non-Muslim) who bear her name, but also because it is the name of the prophet’s favorite wife, and at the same time a figure who is no stranger to controversy.

Aicha, the Prophet’s wife

The Prophet Mohammed’s Aicha was an eloquent, intelligent woman whose wisdom was used on numerous occasions by the Messenger of God. Aicha occupied positions in the political and military spheres of the Ummah that caused the appearance of many detractors and the awakening of many envies. But it was an anecdotal episode that is related with dyes of chivalrous novel, the throwing weapon that was used by the enemy clan of Mohammed, to accuse his favorite wife of adultery[2] (Martínez Carrasco, 2020, p. 24).

Despite this conflict and others that will follow, especially after the death of the prophet and the beginning of the first fitna, it is clear that Aicha’s actions resembled more those of “a lady of war” than a simple rebellious and spoiled young woman as she was portrayed by her detractors: “Aicha is a paradigmatic example of that will to break certain clichés that have to do with the confinement of women in the private space of the home and without any involvement in public life” (Martínez Carrasco, 2020, p. 40).

Could Aicha bint Abu Bakr herself be the source of inspiration for Cheb Khaled? Probably not, but the mother of the believers could be an example for the growing feminism that was permeating society and that inspired the theme of this song.

To enter into an in-depth analysis of the historical, social and political context that gave birth to Islamic feminism as we know it today, we must establish the historical position that Islam itself reserves for women.

In the Islamic religion, as in any monotheistic religion, male-female relations are asymmetrical, that is, women are considered inferior to men, and although this is not an issue that concerns exclusively the Islamic world, it seems to be one of the characteristics that most attract our attention from the Western point of view. The Koran speaks about the rights of men and women in these terms: “Women have the same rights over their husbands as they have over them, as is known; but men have preeminence over them” (Koran II, 228) or also about the validity of the witnesses “If you do not find two men, ask for a man and two women with whom you are satisfied […] if one of them errs, the other will make her remember” (Koran II, 282).

Women rights

Perhaps because this female emancipation has occurred later, or has been silenced more easily; perhaps because tradition and religion are more established in the private and political sphere than in the West, the fact is that women in Islamic countries enjoy fewer rights than in Western countries. But does this scenario respond to an exclusively religious issue, or does this pretext hide the patriarchy[3] that does not allow deconstructing a situation that for centuries has been favorable to it?

This is the objective of Islamic feminism: to deconstruct the supposed general knowledge by going to the core of Islam, the defense of equal rights and social justice.

If we approach the first verse exposed in previous paragraphs and read it from a feminist point of view, we can interpret that these rights are different because both sexes have different capacities, then the question arises: Why should the rights reserved to men be considered better than those of women? If in the first lines of the verse we can see the affirmation that both sexes have similar rights (Touzenis, 2007).

If we consider the second sura exposed, explained from the perspective of Islamic feminism, we would resort to scientific facts that would justify “the loss of female memory” in exceptional cases such as pregnancy, postpartum or menopause (Touzenis, 2007), thus justifying the need for two women as witnesses, as indicated in the Koran.

This exposition of the different interpretations that can have the azoras, would answer the question posed above. The Koran, like any written text, is subject to interpretation even though it has been a revealed book, it must be adaptable to the times: “In any case, they understand that such discriminatory texts cannot be considered normative here and now” (Tamayo, August 24, 2009) and this is the objective of Islamic feminism: to deconstruct the supposed general knowledge by going to the core of Islam, the defense of equal rights and social justice. This feminism, which at the beginning of its birth, refuses to call itself “Islamic” (Badran, 2009, p. 70) resurfaces in the 1990s with the intention of readjusting the initial message after centuries of manipulation.

Is Islamic feminism limited to this field or is it the fruit of other claims? We can state with almost complete certainty that Islamic feminism is an “unwanted child” [4] of political Islam. Although there are authors (and above all women authors) who think and maintain the opposite. That it is a product of political Islamism, a product of easy sale, especially the so-called “Islamic feminism” of the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century (not the “classic” feminism of the first half of the twentieth century, Hoda Sharawi and her companions) (Miguel Grajales Pedrosa, 2022).

As Margot Badran comments in “Feminism in Islam: Secular and Religious Convergences”, Islamic feminism emerged in the areas where political Islam had lasted the longest, these attempts to silence women’s demands only led to these troublesome feminist groups, in the eyes of the conservatism of political Islam, to separate from it in favor of their own demands (as in the case of Turkey) in addition to those arising as a result of the anti-colonial struggles of the Maghreb. With these anti-colonial struggles, the first demands for gender equality also arise, which will be embodied by the figure of Huda Shaarawi, who uncovered the veil to show her face as a protest in the 1920s, to later end up founding the Egyptian Feminist Union (White, July 16, 2020).

Islamic feminism and its detractors

But like any other protest movement, Islamic feminism is no stranger to detractors who believe that Islam’s own term “submission” cannot possibly go hand in hand with the equal rights that feminism in general hails. One of the most critical on this issue has been Wassyla Tamzali, an Algerian activist, who believes it is impossible for Islamic feminism to exist by itself because it has completely opposite meanings, even considering that it would be a product created to contribute to female alienation.

Islamic feminism is an “unwanted child” of political Islam, although there are authors (and above all women authors) who think and maintain the opposite.

In this connection, there is also the argument that Islamic feminism would not include all Arab women, but only Muslim women. Islamic feminism cannot be understood as a political movement in the same way that there is no Christian feminism[5] since religion and the state should be two distinct subjects that cannot converge in the same way. They insist that Muslim women refuse to join the feminist movement because it does not reflect their identity and their real situation but that is no justification for creating a movement around a religion (Özgür Günes Öztürk, September 30, 2018).

But this vision of Western feminism is not an issue that really concerns us because it does not portray the context of women in the eyes of Islam and citizens of Islamic countries, just as, as we have commented above, it does not respond to the realities of Muslim women.

Ziba Mir Hosseini could refute the above arguments against Islamic feminism, stressing especially that they cannot deny the reality of their states. The emancipation of Muslim women is not possible without Islam because the states of which they are citizens are rarely secular. This is one of the reasons, among many others, why Islamic feminism becomes indispensable.

In turn, the arguments in favor of Islamic feminism again revolve around an issue that we have been discussing throughout our narrative, the struggle against patriarchal manipulation of the Holy Book, the Sunna and the Hadith.

Faced with the neglect of the realities of Muslim women by hegemonic or Western feminism, this Islamic feminism, created by them and for them, becomes essential for now and for the coming days.

Before the oxymoron proposed by the Algerian activist Wassyla Tamzali we have the redundancy that means for Sirin Adlbi Sibai feminism and Islam, equal rights. It is very important to highlight the idea that slips from Sirin’s argument against hegemonic feminism or western feminism, as she comments: “Hegemonic feminism has been imposing a series of discourses, it has been directed towards a certain subject, which are white, western, bourgeois women… […] This type of feminism has excluded all those women of the so-called third world”.

Hegemonic, or Western feminism

Faced with the neglect of the realities of Muslim women by hegemonic, or Western feminism, this Islamic feminism, created by them and for them, becomes essential for now and for the coming days because it portrays the real situations and conflicts they have to face continuously. That is why from different parts of the society composed of Muslim women, the veil that generates and has generated so much controversy has become a symbol of protest, not only religious, but also feminist. Because Muslim women, besides facing male chauvinism, also have to confront the racism of Western society (Leticia Romero, January 11, 2022).

This veil for many women is a claim of their capabilities, their origins and the unequal conditions and opportunities to which they will be subjected. Despite the fact that the liberation of its use for women before them represented a break with respect to the patriarchal construct. This Western vision of the veil as a symbol of repression, unconsciously responds to the colonialist sentiment and the infantilization of the West in which it becomes essential to “liberate” the population subjected to an oppressive state, regardless of the individual freedoms of each of the citizens.

We can therefore conclude that, without a doubt, Islamic feminism has a future projection embodied in activists such as Imane Raissali (Miss Raissa) Hajar Brown or Sirin Adlbi Sibai, among many others, which will continue to adapt as it has been doing during the last decades to the concrete needs of the social and political context. Cheb Khaled’s “Aicha” remains a hymn that resounds in the ears of women and young girls who dream that freedom, far from the golden cages, will one day be real.

Footnote references:

[1] Rai music was born in Oran in the early 20th century and its use spread throughout the Maghreb. The songs feature a tone of protest about external, but also internal issues (Gómez Muñoz, July 28, 2018). [2] The also called “affair of the lie” (‘ifk) (Martínez Carrasco, 2020, p. 30) involved a direct attack on the honor of the prophet’s wife and therefore on Mohammed himself and the entire Ummah. For, as in other cultures, for a long time women were in charge of preserving the honor of the families. [3] The critique of religious manipulation by patriarchy runs through all the arguments put forward by authors who have dealt with Islamic feminism (Badran, 2009, p. 70) (Haddad, 2010, p. 24). [4] We use the term “unwanted child” in reference to the historical relationship between political Islam and Islamic feminism. Both respond to early anti-colonialist movements and the development of pan-Arabism as an identity, but there is a conflict of political ideas between the two despite the common nexus. The conservatism of political Islam clashes head-on with the liberalism and emancipation of Islamic feminism. [5] This question could be refuted because Christian feminism also exists (Moreno Seco, 2005).Aisha – Cheb Khaled

Bibliography:

ALDIBI SIBAI, S. (September 11, 2017) “Más allá del feminismo islámico: redefiniendo la islamofobia y el patriarcado” Journal of Feminist, Gender and Women Studies nº 6. Autonomous University of Madrid.

BADRAN, M (2009) “Feminismo islámico en marcha” In: BADRAN MARGOT, Feminism in Islam: Secular and Religious Convergences. Oxford, Oneworld Publications (pp. 69 – 84).

BRAMON, D. (2007) “Capítol 4. Les desigualtats que no provenen de la doctrina de l’islam”. In: Dolors Bramon. Ser dona i musulmana. Barcelona: Cruilla: Fundació Joan Maragall (pp. 117-147).

BLANCO, J. (July 16, 2020) “Feminismo islámico, una lucha contra el colonialismo y el patriarcado” El Orden Mundial. Feminismo islámico, una lucha contra el colonialismo y el patriarcado – El Orden Mundial – EOM.

DORIA, S. (March 27, 2011) “El feminismo islámico no existe” ABC International. ABC. “El feminismo islámico no existe” (abc.es).

GALARRAGA GORTÁZAR, N. (November 1, 2010) “Feminismo e islam pueden ser una buena pareja” El País. “Feminismo e islam pueden ser una buena pareja” | Society | EL PAÍS (elpais.com)

GÜNEZ OZTÜRK, O. (September 30, 2018). “Cuestionando el feminismo islámico” El Salto Diario. Feminismos | Cuestionando el feminismo islámico – El Salto – General Edition (elsaltodiario.com).

FERNÁNDEZ GUERRERO, O. (2011). “Las mujeres en el Islam: Una aproximación” BROCAR, 35. UNED (Centro Asociado de La Rioja) (pp. 267 – 286).

FEIXAS, T. (2021) “Mujeres Valientes” Ediciones Península. Barcelona.

GÓMEZ MUÑEZ, J (July 28, 2018) “La música “Raï”, el blues del Magreb” France24. “Raï” music, the Arab blues of the Maghreb – Culture (france24.com).

HADDAD, J. (2011) “Yo maté a Sherezade. Confesiones de una mujer árabe furiosa” Random House Mondadori, S. A. Travessera de Gràcia, Barcelona (pp. 17 – 30).

KHALED (1996) “Aicha” Capitol Music France. (631) Khaled – Aicha – YouTube

MARTINEZ CARRASCO, C. (2020) “ʿʿĀʾʾisha bint abī bakr: mujer, guerra y poder en la arabia paleo-islámica antes de la primera fitna” University of Granada. (pp. 17 – 42).

MEDINA, M. A. (February 1, 2017) “El feminismo islámico es una redundancia, el islam es igualitario” El País. “El feminismo islámico es una redundancia, el islam es igualitario” | Mujeres | EL PAÍS (elpais.com)

MORENO SECO, M. (2005) “Cristianas por el feminismo y la democracia. Catolicismo femenino y movilización en los años setenta” Fundación Instituto de Historia Social (pp. 137 – 153).

ROMERO, L (January 11, 2022) “Miss Raissa: Llevo velo para que otras chicas puedan ver que pueden hacer lo que les dé la gana” RTVE Miss Raissa: “Llevo velo para que otras chicas vean que pueden hacer lo que les dé la gana” (rtve.es)

TAMAYO, J.J. (August 24, 2009) “Mujeres en el islam: tradición o emancipación” El País. Mujeres en el islam: tradición o emancipación | Opinion | EL PAÍS (elpais.com)

TOUZENIS, K. (2007) “Looking Through Veils. Women’s rights in Islam”. Journal of Philosophy of International Law and Global Politics.

VIDAL CASTRO, F. (2016) “El tratamiento de la infancia y los derechos del niño en el derecho islámico con especial referencia a la escuela mālikí y a al-Andalus”. Anaquel de Estudios Árabes, vol. 27 (pp. 201 – 238).

No Comments