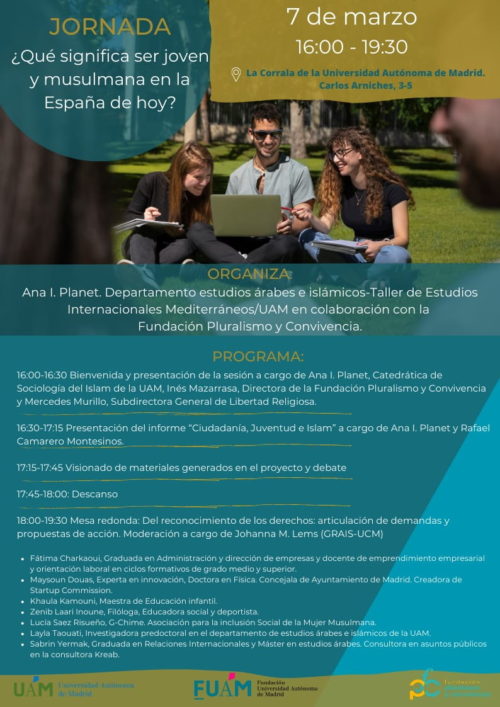

On March 7th the Islamic Culture Foundation (FUNCI) attended the conference “What does it mean to be a young Muslim woman in Spain today?”, organized by Ana I. Planet, Professor of Sociology of Islam at the UAM, with the Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies, in collaboration with the Pluralism and Coexistence Foundation. The event was structured in two parts. The first one consisted of the presentation of the report “Citizenship, Youth and Islam”, by Ana I. Planet and Rafael Camarero Montesinos and the second was a round table, under the title “From the recognition of rights: articulation of demands and proposals for action” moderated by Johanna M. Lems, professor and researcher of GRAIS at UCM.

Voices of young Muslim women: an energizing force for social change

The report “Citizenship, Youth and Islam. The associationism of young Muslims in Spain” is the result of the research project “Citizenship, Youth and Islam”, developed through a collaboration agreement between the Foundation of the Autonomous University of Madrid and the Pluralism and Coexistence Foundation. The report represents an alignment between academic research and citizen action, as indicated by Inés Mazarrasa, Director of the Pluralism and Coexistence Foundation, who considered that working on the religious phenomenon from young Muslims allows contact with the daily reality of citizens.

Based on the plural reality of Spanish society, the report takes into account the diversity of religious beliefs and the multiple practices and actions that derive from them. In order to broaden knowledge about this social reality, the project goes beyond the study of religious and cultural practices, traditionally associated with Islam, to focus on the field of citizen participation and associative initiatives led by young Muslims. In this way, the project seeks to access the spaces of associationism of these young people to get to know them, with the intention of contributing to the improvement of public policies associated with the management of religious pluralism in Spain.

Based on the plural reality of Spanish society, the report takes into account the diversity of religious beliefs and the multiple practices and actions that derive from them.

Ana I. Planet and Rafael Camarero pointed out that, “despite the fact that the search for spaces for citizen expression and community activities has not been especially worked on, there are very powerful voices of young Muslims in the Spanish associative fabric”. In order to access these voices, the project worked to identify meeting places for young Muslim in order to subsequently initiate a series of conversations to learn about the concerns and internal discourses of these youths. The conversations revealed a heterogeneity and dynamism in Muslim young people, as well as a plurality of associative experiences. Nevertheless, one of the most remarkable characteristics of the report is the high level of participation of women. Associations promoted only by and for Muslim women stand out, as well as the important role that many of them play in the different initiatives. It is, therefore, Muslim women who are the protagonists in the struggle for social change.

The question of identity appears to be the main concern of most of the associations. Above all, in the first associations, because in the more recent ones it represents a gateway to other more material issues affecting Muslim youth. Another common point is the demand to occupy public space on equal terms, with many of the associations responding to the logic of searching for and creating a safe space of their own. Likewise, almost all the associations share the same difficulties, which are related to economic funding, communication with public institutions, administrative obstacles or the need to exercise a highly committed volunteer work.

On the other hand, the fight against Islamophobia is also a constant in youth associations. However, this is mainly approached from two directions. One is the anti-racist struggle while the other relates exclusively to religious rights. One of them is the anti-racist struggle, while the other is exclusively related to religious rights. In any case, the report shows that the fight against Islamophobia is not a priority, especially in comparison with other aspects that directly affect the daily lives of young people. In this definition of priorities, Rafael Camarero pointed out how many of the priorities of Muslim youth could be extrapolated to other groups of society, thus constituting the Muslim youth associative movement as the spearhead of the movement for social change in Spain, which affects many areas.

Many of the priorities of Muslim youth could be extrapolated to other groups of society, thus constituting the Muslim youth associative movement as the spearhead of the movement for social change in Spain, which affects many areas.

By way of conclusion, the Report highlights the four axes along which the priorities of young Muslims in Spain are articulated. In first place, the issue of safe leisure appears, not only because young people demand to have fun, but also because it is the meeting point of many associations. Secondly, Muslim youth were aware of living in a society that does not know them and demanded social recognition as full citizens. Thirdly, the issue of education and equal opportunities is presented, as well as the concern for economic inequality and insertion in the labor market. Finally, the last priority is related to religious rights and the claim to occupy public space, the teaching of the Islamic religion in schools and the availability of mosques and Muslim cemeteries.

Associationism under debate

In the second part of the event, a round table discussion was held, in which various aspects regarding the associationism of young Muslim, as well as other aspects related to being a Muslim woman in Spain, were debated. Participants included Fatima Charkaoui, teacher of business entrepreneurship and career guidance; Maysoun Douas, PhD in physics, councilor of the Madrid City Council, creator of Startup Commission; Khaula Kamouni, early childhood education teacher; Zenib Laari Inoune, philologist, social educator and sportswoman; Lucía Sáez Risueño, from the G-Chime Association; Layla Taouati, pre-doctoral researcher in the Department of Arab and Islamic Studies at the UAM and Sabrin Yermak, public affairs consultant at Kreab.

In a first round of questions, Khaula Kamouni began the dialogue by acknowledging the workload behind the associative environment, and tied the construction of community spaces to arduous work. In this sense, she indicated that they do not stand on their own and that it is necessary to “juggle in order to find a way to continue in the associations”. This opinion was shared by the vast majority of the participants. For example, Fatima Charkaoui indicated that “if your job is not flexible, there are times when, no matter how much you are passionate about something, you cannot devote time to it”.

Along these lines, Maysoun Douas spoke about the need to professionalize associative work so that it can be sustainable while generating positive impacts. She also stressed the importance of social entrepreneurship, and mentioned initiatives such as those of Ashoka and the Google Foundation. Lucía Sáez also claimed the need for professionalization, based on the experience of her own organization, G-Chime, and expressed the importance of professionalizing accompaniment so as not to replicate external discrimination. She also took a critical stance towards other spaces and encouraged non-participation in discriminatory spaces.

Layla Taouati spoke about the Association Sobre los Márgenes, to which she belongs, presenting it as a form of accompaniment based on experience. Likewise, together with Zenib Laari Inoune, she expressed the importance of spaces in which to share an identity. More specifically, Zenib argued that “adolescence is a very critical stage in which the first identity crises appear, since many young people live between two realities, one familiar and communitarian and another social”. In this sense, she pointed out that “the emergence of associative spaces is crucial as places in which to develop one’s own fluid identity, without inquisitions of any kind”.

It is, therefore, Muslim women who are the protagonists in the struggle for social change.

At the same time, Sabrin Yermak told her life story as a Muslim woman born in a small village where there were no associations. She commented on the difficulty of living between two worlds and how much she would have liked to belong to an association during her adolescence. She also claimed the importance of religious knowledge, and stated that associations play a fundamental role in its diffusion. She added that with knowledge “you realize that you can have your own Islam”, and that “the beauty of Islam is to find your particular relationship with God”.

At this point in the debate, Johanna M. Lems threw out the following questions, “who can help from outside?, what ally do you need?” To which Fatima Charkaoui replied that “the problems are crossed by many axes, but those who have the initiatives are often the victims”. In this way, she pointed out that the institutions should intervene, above all, with financing issues that cannot come out of the pockets of private individuals. Fatima also pointed out the existence of a structural and institutional racism that implies the non-recognition of the problem, and considered that it was very difficult to fight it through private initiatives because “if it is not recognized, it is not solved”.

“The problems are crossed by many axes, but those who have the initiatives are often the victims”.

On the other hand, Zenib Laari Inoune pointed out the internal problems of the Islamic Commission of Spain, and questioned its relationship with the Islamic community. In relation to this, Layla Taouati launched a reflection on the concept of community, wondering if “we really want to form ourselves as a community”. At the same time, Maysoun Douas, after recognizing the malfunctioning of the Commission and the need for reforms, urged individual and associative activism for those issues of a more socio-political nature. In the same vein, Mercedes Murillo, Deputy Director General of Religious Freedom, intervened to point out the religious quality of the Islamic Commission and its limits of action in areas such as social issues.

Lack of knowledge about religious rights, and pedagogical work

At the end of the round table, the participants commented on the problem of the lack of knowledge about religious rights, as well as the need for pedagogical work. Along these lines, Sabrin Yermak added that “what predominates nowadays is hate speech, which should be the focus of attention. She thus affirmed that “it is everyone’s job to assume the responsibility of participation and political activism and to interact with public institutions, because political action is what makes things change.” With this, the table concluded by appealing to the very important work of activism and associationism of young Muslims, as well as recognizing the existing workload behind each project and initiative with the will of social change.

The development of the Conference allowed, on the one hand, to know the main conclusions of the research project “Citizenship, Youth and Islam” and, on the other hand, it was an opportunity to listen to the voices of Muslim women with experience in Spanish youth associations. With this, it is worth considering the existence of an agenda created by young Muslims who claim to incorporate their religion into citizenship as a way of life, and who stand up against stigmatization, discrimination and Islamophobia. The importance of women in this struggle should also be emphasized, as they are the ones who are most willing to demand equal citizenship and equal rights.

Consult the report here

Ainara García Sánchez

No Comments