Alfonso Casani – FUNCI

In February 1991, in the midst of the political crisis caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union, three states came together with the aim of accelerating the process of European integration and promoting a convergence of their policies, economies and cultures. Bringing together Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia (now numbering four states, following the latter’s split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia), the agreement led to what is now known as the Visegrad Group. This group has today transcended policy coordination to become one of the main lobbies against EU policies in Brussels and the reception and reception of migrants and asylum policies promoted by the EU.

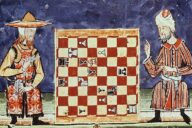

The place chosen for their first meeting, Visegrad, was charged with symbolism and recalled the meeting held by the monarchs Charles I of Hungary, Casimir III of Poland and John I of Bohemia in the 14th century to confront the territorial ambitions and taxation of the Habsburgs[1]. This ‘sovereignist’ ambition is still present today, through demands for greater powers for national parliaments or the defence of greater border control.

In order to understand the impact of this group on Europe and the European Union, it is necessary to take into account their promotion of three interrelated policy lines, which advocate: a different conception of what the European Union should be, a new understanding of the democratic state, and the dissemination of a discourse and position of a markedly Islamophobic nature.

A European Union with fewer competences

The current functioning of the European Union is one of its main areas of criticism, and yet they should not be understood as an anti-Europeanist group, but rather as anti-Brussels[2]. In practice, the Group not only came into being to promote European integration but has benefited greatly economically from its membership of the EU. Despite this, these countries have become a focus of pressure against policies emanating from Brussels, a pole that advocates a new orientation of this supranational body, a partial devolution of competences to national parliaments and greater border control.

As Mateusz Morawiecki, Poland’s prime minister, said last year in remarks marking the 30th anniversary of the group’s formation:

“the strength of the Visegrad Group today is based on the synergy of EU action, a stronger negotiating position in EU structures and the representation of our international strategic interests in the international arena.”[3]

In 2015, the respective prime ministers of Poland and Hungary, Jarosław Kaczyński and Viktor Orbán, called for a “counter-revolution” in Europe, “altering the European Union, its structures and decision-making process”[4].

Although the statements made by Olaf Scholz, the current German chancellor, last September in Prague in his first position on the EU as head of the German government strongly advocated Europeanism, they also reflected a growing certainty, the possibility of a multi-speed European Union, with a greater or lesser willingness to integrate its member states.

An illiberal State

Already in 2014, in a speech to the students of the Summer Free University, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán declared in a speech that he wanted Hungary to exemplify a new conception of the state[5]. A new form of state development that would overcome the problems faced by today’s liberal democratic state and lead instead to the so-called new “illiberal state”. This would be a sovereigntist state, with a differentiated notion of freedom, distinct from the individual freedom of the liberal state, and in which the latter would inevitably be subordinated to the interests of the nation.

The adoption of this label is striking given the negative connotations with which the “illiberal state” has traditionally been associated. Developed as a theoretical concept in 1997 by international relations analyst Fareed Zakaria[6], “illiberal democracy” refers to hybrid, non-democratically full regimes in which the civil rights of the population are systematically violated. Although these democracies hold elections on a regular basis, these processes are far from free and transparent due to a lack of electoral competition, weak rule of law and the exclusion of minorities or dissenting voices.

A bastion of Islamophobia in Europe

Discrimination against Muslim minorities, in word or deed, is one of the main examples of the country’s weak civil rights. An ideological pillar of Fidesz, the party led by Orbán in Hungary, this rhetoric shows the process of making the Muslim population a scapegoat for the country’s problems over the last decade.

When we look at the emergence of this rhetoric in the region, two aspects are particularly striking: the virtual absence of anti-Muslim discourse prior to 2015, and the low number of Muslims resident in the four countries that make up the group. Hungary, for example, has a Muslim population of only around 5,000[7], compared to the country’s 10 million inhabitants. This means that Islam occupies a minority position in the country, which justifies the low political importance it had received until the middle of the last decade.

Its incorporation into the political discourse coincides with the moment of greatest intra-European tension in the face of the so-called refugee crisis and the emergence of the debate on the need to agree on mandatory quotas of refugees to be taken in by the different members of the Union.

They also coincide with the perceived rejection of Hungarian migrants living in other European countries, and with a strengthening of the nationalist-Christian profile of Fidesz, responding to domestic political issues[8]. In this context, the discourse of this conservative party benefited from the debate generated by the violence of the Islamic State and the spread of international attacks on European soil, mainly in France. Thus, as the party’s national-Catholic roots grew stronger, its anti-immigration and Islamophobic positions increased.

Faced with the urgency of receiving refugees from Syria arriving on European soil, Orbán announced Hungary’s readiness to take in only refugees of Christian faith. As he justified in an opinion piece published in the German daily Frankfurter Allemaigne:

“This is an important question, because Europe and European culture has Christian roots – and isn’t it worrying that Europe’s Christian culture is hardly in a position to defend its own Christian values?”[9]

This discourse was quickly transferred to the national level, due to the little opposition this message encountered, considering the paucity of Muslims resident in the country. “Shall we be slaves and free men, Muslims or Christians”, asked the president of the National Assembly[10]. asked the speaker of Hungary’s National Assembly in a speech to the youth of the Christian Democratic People’s Party.

A European trend

This discourse is not unique to Hungary, but is shared by all four countries in the group, feeding back on each other and finding a similar pattern of operation. In the Czech Republic, where the Muslim population is estimated at less than 0.02% of the population[11], discrimination against Muslims and the expression of their faith has increased considerably in recent years, while in Slovakia, in 2016, a law was passed to prohibit the recognition of Islam as an official religion. Similarly, in the midst of the refugee reception debate in 2016, Milos Zerman, President of the Czech Republic, argued that the arrival of asylum seekers was a new invasion strategy by the Muslim Brotherhood[12].

The resonance that this discourse has found in Europe is also very significant. In Austria’s 2017 elections, right-wing and far-right candidates boasted of their closeness to Victor Orbán and willingness to align themselves with his migration policies[13], while across Europe, parties such as the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, the Northern League in Italy, or the National Rally and Reconquest in France use the Muslim population as a scapegoat to justify the socio-economic crisis Europe is facing and promote chauvinist policies with an emphasis on sovereignty and the protection of each country’s nationals.

All these movements share a common perception that sees globalisation and supranational construction processes as a threat, and that their national citizens have been the losers in the processes of modernisation and the global financial crisis of 2007. In this process, anti-Islamic rhetoric, discrimination against Muslims, and the defence of Christian or Judeo-Christian values become a tool for denouncing much larger structural, political and economic elements that have little to do with Islam, but whose pernicious effects profoundly affect the Muslim population living on the continent.

References

[1] Ferrero, Ángel (2021). “El grupo de Visegrado cumple 30 años”, Política Exterior, 22/02/2021. https://www.politicaexterior.com/el-grupo-de-visegrado-cumple-30/

[2] https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-internacional-42879957

[3] Ferrero, Ángel (2021). “El grupo de Visegrado cumple 30 años”, Política Exterior, 22/02/2021. https://www.politicaexterior.com/el-grupo-de-visegrado-cumple-30/

[4] Rupnik, J. (2017). La démocratie illibérale en Europe centrale. Esprit, , 69-85. https://doi.org/10.3917/espri.1706.0069

[5] The speech can be seen in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHxg3Aoir6w

[6] Zakaria, Fareed (1997). “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy”, Foreign Affairs, November 1997. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/rise-illiberal-democracy

[7] Sayfo, Omar & pall, zoltan. (2016). Why an anti-Islam campaign has taken root in Hungary, a country with few Muslims. V4Revue.

[8] Ibid.

[9] https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2015/09/150904_crisis_migratoria_europa_debate_islam_musulmanes_religion_hungria_paises_este_lv

[10] Sayfo, Omar & pall, zoltan. (2016). Why an anti-Islam campaign has taken root in Hungary, a country with few Muslims. V4Revue.

[11] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/11/13/czech-republics-tiny-muslim-community-subject-to-hate

[12] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/czechrepublic/12082757/Muslim-Brotherhood-using-migrants-as-invasion-force-to-seize-control-of-Europe-Czech-president-claims.html

[13] https://themaydan.com/2017/11/converging-islamophobias-europe-visegrad-four-countries-western-forerunners/

No Comments