We recover this article by Daniel Gil-Benumeya, professor at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) and researcher and collaborator of the Islamic Culture Foundation, and Laura Mijares, professor at the UCM, published by El Salto Diario. The article delves into the causes and structural elements on which Islamophobia is built, offering an updated definition of Islamophobia.

Despite its name, Islamophobia is not fear of Islam. It is a complex phenomenon composed of several factors. On the one hand, it is a form of racism against people who are Muslim or read as such, regardless of their actual religious practice. Racism in two senses: first, because it racializes Muslim people, that is, it attributes to them a series of characteristics that tend to function as an explanatory key to everything they think, say or do, in the same way that biologicist racism attributed different capacities and behavioral tendencies to human “races”. Under an Islamophobic view, a Muslim person is inexorably determined by his or her belonging to Islam, by his or her “Muslimness”, which is defined according to the set of representations that non-Muslim societies have of what it means to be Muslim. The greatest evidence of this, although not the only one, is the discourse on “radicalization”. For what does it mean to be radicalized if not to fully develop a behavior that is supposed to be latent? Once it is established that Islam is intrinsically violent, the myth of “express radicalization” means that anyone of Muslim religion or culture is susceptible to becoming a mass murderer overnight. Conversely, we find the category of acceptable Muslim people, those who are the “moderates,” i.e., by definition those who do not fully develop the (perverse) potentialities of their religion or culture.

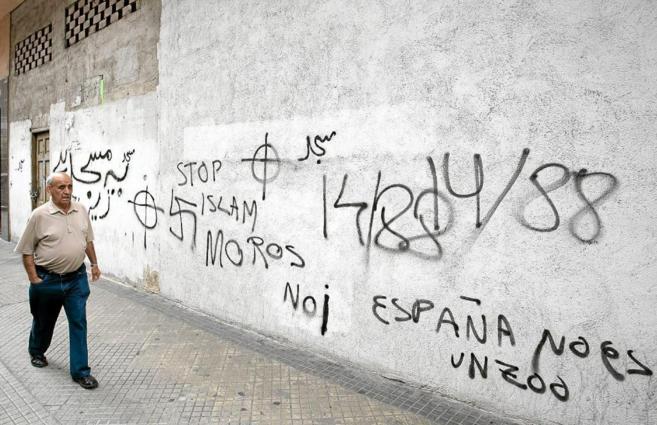

Islamophobia, of course, is also racism in a more classical sense: the vast majority of Muslims are not “white”. This has nothing to do only with skin tone, but with the colonial logics of world hierarchization. In this sense, Islamophobia naturalizes the use of cruder expressions of racism. Throughout Europe, the rejection of the Paki, the Beur, the Moor is the result of the problematization of Islam and cultural difference.

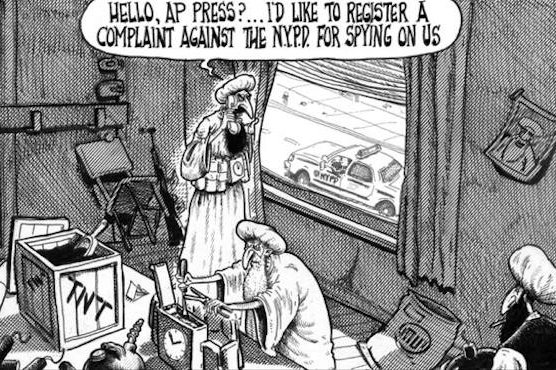

Therefore, Islamophobia is also a certain construction of Islam as a monolithic religion and culture, static and intrinsically violent, sexist, etc., which allows the questioning of its legitimacy and its presence in the supposedly “enlightened” and “secular” societies of the global North. Herein lies one of the difficulties in dealing with Islamophobia, as the Islamophobic discourse interferes self-interestedly in the legitimate criticism of certain approaches or ideologies that are claimed to be Islamic.

Islamophobia, in the 21st century, is as respectable in Northern societies as anti-Semitism was a hundred years ago. In fact, it is enough to substitute Jews or Judaism for Muslims or Islam in a multitude of headlines and statements both then and now to automatically go from an intolerable display of racism – subject to criminal consequences – to a simple manifestation of common sense, more or less politically decanted but for which few people would be shocked. Proof of this is the scant interest aroused by its political analysis, sometimes even in sectors that claim to be anti-racist, beyond considering it an electoral resource for the far right.

Islamophobia fits into frameworks of thought solidly anchored in the cognitive structure of Modernity: racism, sexism and social class. Racism naturalizes the place that certain areas of the world and their inhabitants should held within the global productive and social structure, and sexism applies the same naturalization on the basis of gender. The idea that Islam opposes modernity and threatens “European values” has been built around the oppression, subordination and need for salvation of Muslim women. Islamophobia is always gendered, not only because women are affected more than men, but above all because the issue of discrimination against women is instrumentalized to justify and legitimize Islamophobic policies. Central to the Islamophobia industry is the global-scale production of Muslim women in need of saving. Debates on Muslim women’s bodies, which have occupied much of the Islamophobic narrative since the first veil controversies in France, would be impossible without the underlying logics that argue that women’s bodies are public patrimony. It relies on the idea that the West or Eurocentric culture has the privilege of defining where liberation or discrimination begin, what is universal and what is particular.

So, in the case of Islamophobia, these structural elements, susceptible of acquiring different racial “colorations”, are combined with a fourth element, which is the extensive Eurocentric, Christianocentric and colonial repertoire that has in Islam its great other. This repertoire was analyzed by Edward Said in the case of European colonialism. In the case of Spain, it has its own characteristics, and is activated, deactivated and reconfigured according to the strategic interests of each moment.

New policies for new racisms

So, in the case of Islamophobia, these structural elements are combined with a fourth element, which is the extensive Eurocentric, Christianocentric and colonial repertoire that has in Islam its great other.

To assert that Islamophobia is a resource of the far right seems to suggest that the latter is merely instrumentalizing a problem spontaneously generated by the traumatic encounter between the West and Islam, through migration, “Islamic” terrorism or political Islamism. However, no social fact constitutes a public problem, not if it produces an objective change in the sphere of social life to which it refers. The condition of possibility of a public problem is that it be constructed as such and socially accepted at the expense of other potential problems, for which there must be social agents who construct and reproduce it for a specific purpose.

Islamophobia was denounced and named as such in the mid-1990s, but it derives from a process that began at the end of the “golden thirties” of capitalism. Two dimensions coincide: an international one, related to the geostrategic interests of the United States and its allies since the late 1960s, and a domestic one, which has to do with the management of immigrant labor, mainly in Western Europe. Edward Said showed early on in Orientalism that pre-war anti-Semitic discourses were being transferred from Jews to Arabs. One reason was the emergence of the Palestinian resistance after 1967, which created the figure of the “Arab terrorist” (airplane hijacker) in a context in which U.S. policy was aligned with Israel. The second reason was the 1973 oil crisis, which spawned a long series of depictions, recycled from anti-Semitism, of fanatical and greedy Arab sheikhs with long noses. Terrorists and sheikhs coincided in their previously unheard-of ability to affect the daily lives of peaceful citizens of the “first world”. Shortly afterwards, the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and more generally the emergence of political Islamism transformed the “Arab” danger into an “Islamic” danger. After the fall of the USSR and the reaffirmation of US hegemony, the bombing of Baghdad inaugurated a “new world order” based on the idea of the “clash of civilizations”. 9/11 and the “war on terror” completed the construction of Islamophobia as an imperial ideology that inherited the old colonial frameworks, including the extensive repertoire of Orientalism.

Meanwhile, in the industrialized countries of Europe, the end of full employment and the welfare state from the 1970s onwards gave rise to the fabrication of an “immigration problem”, which served to make labor -both immigrant and autochthonous, which was forced to compete with it- more precarious and therefore cheaper, and created a suitable scapegoat for the frustrated hopes of the native working class. Neoliberalism popularized xenophobic discourses that until then belonged to remains of ultra-conservative and far right-wing sectors. They transformed them into an asset, no longer political but post-political, insofar as they were presented as a matter of “efficient management”, transversal or alien to political ideologies. This “immigration problem” circumvented common definitions of racism, questioning the limits of multiculturalism and the difficulty for people from certain “cultures” – coincidentally, those who made up the bulk of the unskilled labor force – to “integrate”. At that point, the emergence of the global “Muslim problem” was used to shore up the stigma attached to the immigrant working class and discredit their demands. The veil issues in France and the Rushdie case in the United Kingdom shaped the discourse of a “clash of civilizations” being fought in the very heart of Europe, an idea that crystallized with the emergence of “Islamic terrorism” at the local level.

Therefore, Islamophobia is not the exploitation of a spontaneous problem. It is an example of moral panic or witch-hunting, a mechanism of social disciplining linked to the new reconfigurations of capitalism. The destruction of Iraq, the massive displacement of populations through conflicts or the privatization of public services (whose deficit is blamed among other things on overexploitation by immigrants) are all forms of accumulation by dispossession. That is to say, a violent seizure of the common good aimed at periodically reiterating primitive accumulation in order to boost the return on capital. The “fight against terrorism” seems to be the door to a sort of post-democracy, a state of emergency or permanent exception as a form of government.

The far right undoubtedly contributes to the production and reproduction of Islamophobia, but it would be a mistake to stop there. To begin with, the very idea of the far right is outdated, if we consider the so-called post-fascisms or right-wing populisms that express themselves in the name of liberal values and which to a large extent are nourished by references taken from the Left, successfully disputing its social base. On the other hand, there are sectors within the Left and the feminist movement that play an active role in legitimizing Islamophobia. In this sense, it is essential to review some of the logics of secularism which, under the pretext of religious “neutrality”, contribute to marginalize and stigmatize minority spiritualities while maintaining – under the idea of “cultural tradition” – the privileges of the majority.

It is necessary to realize that if racism is not a mere collection of prejudices but the naturalization of a power relationship, it could not occur without the prior collaboration of the State apparatus.

It is necessary to realize that if racism is not a mere collection of prejudices but the naturalization of a power relationship, it could not occur without the prior collaboration of the State apparatus. The greatest agent of Islamophobia and at the same time the least named is the public institutions, which are the ones that allow the reproduction of stigma through legally established devices of violence and disciplining. The repression of “jihadism” gives continuity to the war on terror on which Islamophobia was founded, turning several million people into a subaltern citizenship subjected to permanent discretion. Likewise, public schools play a less evident but equally important role through the programs of prevention of “radicalization” (such as PRODERAI in Catalonia) and the repression of the corporealities/spiritualities that are considered Muslim, which are associated with an illiberal agenda that challenges the liberal-secular project that the school embodies. Even if the public authorities do not form a homogeneous block without fissures or contradictions, it is difficult to see in them a neutral and arbitrary instance in matters of racism, unless racism is reduced to a problem of “tolerance” in interpersonal relations and not a central mechanism of (re)production of a certain social order.

Source: El Salto Diario

No Comments