Omar Al Mukhtar was one of the main leaders of the struggle against the colonization of Libya by Italy, a struggle that transcends the race for the domination of Africa by the European powers, and is also framed in the conflict generated by the rise of authoritarianism on the continent, serving as a prelude to both World War I and World War II. Despite all this, the effort of this nationalist leader is little remembered, a consequence of the Eurocentric zeal of these international war conflicts, which ignores its profound impact on other regions, such as the southern shore of the Mediterranean.

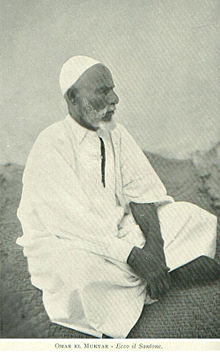

With an almost epic nature, the biography of Omar Al Mukhtar tells the story of an early orphan, educated in a Koranic school, who became a spiritual leader of the country and later, advanced in years, became a nationalist leader in the fight against the occupation of the country by Italy.

Early years and religious training

Omar Al Mukhtar was born into the Minifa tribe in the village of Zawiyat Janfur, a small coastal town in the east of the country, near the Egyptian border, around 1860. Orphaned from an early age and following his father’s designs, Omar came under the tutelage of the religious leader Sharif Al-Ghariani, who educated him in the local madrasa (Koranic school) and taught him the Koran. His education left a strong imprint on Al Mukhtar, and gained him access to Jaghbub University, affiliated with the Senussi Sufi order (itself linked to the country’s monarchy), which would have an important impact in his future and training.

Omar Al Mukhtar was born into the Minifa tribe in the village of Zawiyat Janfur, a small coastal town in the east of the country, near the Egyptian border, around 1860. Orphaned from an early age and following his father’s designs, Omar came under the tutelage of the religious leader Sharif Al-Ghariani, who educated him in the local madrasa (Koranic school) and taught him the Koran. His education left a strong imprint on Al Mukhtar, and gained him access to Jaghbub University, affiliated with the Senussi Sufi order (itself linked to the country’s monarchy), which would have an important impact in his future and training.

After graduating from the university, he served as a sheikh (religious leader) in the city of Zaiyat Al-Qusour and later as a Senussi leader in the territories of Sudan. Until then, his life had been linked to spirituality and education. It was not until 1899, when he was 39 years old, that his life took on a military and combative tinge, when he was sent to Chad to fight against the French colonist forces. It was on that trip that he earned the nickname by which he is known to this day, “the lion of the desert”. It is said that he fought (and was victorious) against a lion during his journey to Chad, although it also symbolizes the bravery for which he was known in battle.

Libya, between Ottoman and Italian ambitions

The occupation of Libya and the resistance of its population is part of both the race for colonization made official by the Berlin Conference of 1885 and the imperialist narrative promoted in Italy after Mussolini’s rise to power and the establishment of fascism.

The territory currently occupied by Libya remained under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire from the 16th century until 1912. The Berlin Conference held between the European powers at the end of the 19th century legitimized the race for the colonization of Africa, but also recognized the occupation of a large part of the continent by the leading empires, mainly the United Kingdom and France.

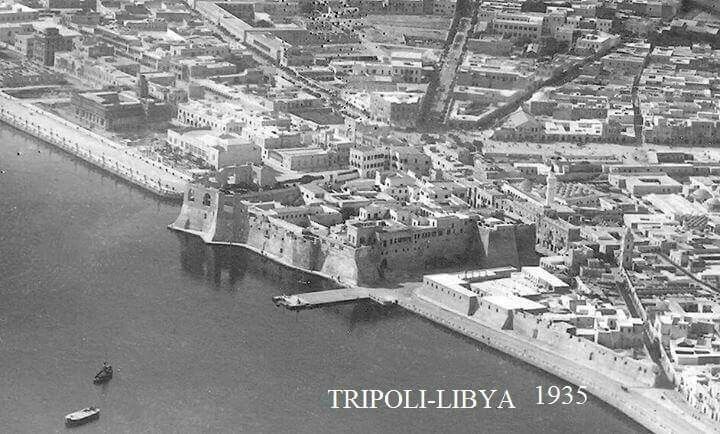

Italy had unified belatedly (in 1870) and had been isolated from this race to dominate Africa. For its part, the Ottoman Empire was already the “sick man of Europe”, as Tsar Alexander III of Russia had called it, and was finding it increasingly difficult to maintain control over its vast territory, which extended over parts of Asia, Europe and Africa. Italy took advantage of the outbreak of the Balkan War in 1912 and the Ottoman Empire’s focus on Eastern Europe to invade Libya and reclaim its territory. Italy had invaded Tripoli and Benghazi a year earlier, in 1911, without the Ottoman forces, retreating inland, and joined by local resistance, being able to cope with the invasion. The attack culminated in the Treaties of Ouchy and Lausanne in 1912 with the withdrawal of the Ottoman Empire from Libyan territory and the claiming of the land by Libya that same year.

Occurring on the eve of the First World War (1914-1918), the conflict showcased the weakness of the Ottoman Empire, but it also allows us to understand the difficulties that the Italian Empire would later have to gain control of Libya, something that would not become effective until the 1930s.

The resistance of Al Mukhtar

The real Italian offensive began in 1922 after Benito Mussolini’s coup d’état in Italy and the launching of a “reconquest” campaign, which was presented as an initiative of recovery of the ancient Roman campaigns in Africa[1]. The story built around the campaign for the effective occupation of Libya, which had been going on for a decade, is an interesting example of historical manipulation with the aim of legitimizing the political line of the moment, which sought to present as a mere parenthesis the almost 14 centuries that had gone by between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the First World War, in order to establish a link between the old Roman glory and the newly proclaimed Fascist Italy.

Over the next decade, Al Mukhtar occupied a central role as a leader of the Libyan resistance against Italian advances. With the country’s king, Muhammad Idris al-Senussi, in exile in Egypt, a considerable part of the political and military responsibilities fell on him as a prestigious religious figure in the Senussi brotherhood, and with military experience[2]. During the following decade, as leader of the Libyan resistance, Al Mukhtar waged a daring guerrilla war against the Italian troops, hindering their advance into the country.

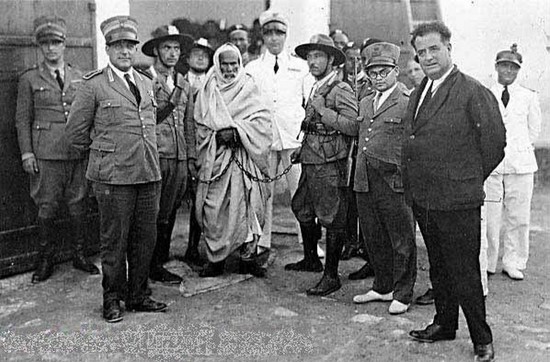

For their part, the Italian troops intensified their pressure on the country’s population, attacking supply lines, carrying out mass executions of the local population and setting up concentration camps for prisoners[3]. Their pressure on the population and their collaboration with various local notables finally led to the capture of Al Mukhtar in 1931. Wounded in an ambush, Omar Al Mukhtar was captured on September 11, and sentenced to death by a military court five days later, on September 16, 1931.

Despite his military victory over Al Mukhtar, Libya would not be completely controlled and unified to Italy until 1939, when Italian Libya was proclaimed. Its annexation entailed the unification of the three territories that make up today’s Libyan territory (Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan) and was, “virtually”, the creation of today’s Libya. After the Italian defeat in World War II, Libya became part of the British unification until 1951, when it finally achieved its independence.

An unknown national hero

The process of Libya’s creation and independence has much to do with the lack of knowledge of this character outside the country. In Libya he is recognized as a war hero and an example of the national struggle against colonization. In fact, his portrait continues to occupy the Libyan 10-dinar banknotes.

The occupation of the territory by Italian troops, however, was ignored until practically the turn of the century. Its colonization has been kept out of the mainstream historical narratives dealing with the colonial race of the early 20th century, which would lead to World War I, and the rise of authoritarianism, which would, in turn, lead to World War II. Its lack of analysis is a consequence of the excessive focus that has been placed on the West, understood as Europe and the United States, in the reconstruction of the events of the world wars. The weight of American and European historians throughout the 20th century has given excessive weight to these geographic regions, often ignoring the impact that international events have had on the rest of the regions or minimizing the events that took place in these regions[4]. The struggle for national independence is thus confined to studies of decolonization, a small section of the study of world history that often fails to transcend borders and become part of general knowledge.

Most notably, Colonel Qaddafi tried to reverse this lack of knowledge about the Libyan national hero by financing the film “The Lion of the Desert” in 1981. It was a war-style film, set against the backdrop of Mussolini’s efforts to gain control of Libya, which chronicled the pursuit of Al Mukhtar by Italian troops. The film featured a prestigious cast and direction, which included Moutapha Akkad as director and Anthony Quinn in the role of Omar Al Mukhtar. Although the film was not as successful as expected, it was an important effort to challenge the official narrative of the Libyan conflict of the early 20th century. In fact, its release was banned in Italy, where it was accused of defamation and censored until 2009[5]. Its broadcast on public television just 13 years ago was the first time that Italy questioned the official narrative about its colonial past.

This event exemplifies well the obstacles faced by the dissemination of knowledge around non-hegemonic historical figures and narratives. Why didn’t indigenous thought develop in Africa, were there no thinkers and scholars, war heroes or events whose importance reached the ends of the earth? Of course there were, but we are often unable or unwilling to see them.

Alfonso Casani – FUNCI

References

[1] https://www.monitordeoriente.com/20210917-recordando-a-omar-al-mukhtar-20-de-agosto-de-1862-16-de-septiembre-de-1931/

[2] https://africa.sis.gov.eg/espa%C3%B1ol/figuras-destacadas/figuras-pol%C3%ADticas/omar-al-mukhtar/

[3] https://www.monitordeoriente.com/20210917-recordando-a-omar-al-mukhtar-20-de-agosto-de-1862-16-de-septiembre-de-1931/

[4] https://www.africaye.org/eurocentrismo-y-mitos-sobre-la-historia-de-africa/

[5] https://blogs.20minutos.es/la-claqueta-de-la-historia/2020/10/12/anthony-quinn-como-el-leon-del-desierto-y-la-resistencia-a-mussolini/

No Comments