Sudan has experienced a turbulent history since independence in 1956, characterized by civil war and clashes between North and South, a succession of autocratic governments and religious tension. (Cover photo by Talal Nayer)

In this context, one figure stands out for his political and intellectual efforts to make Sudan a more egalitarian, peaceful and democratic country: Mahmoud Muhammad Taha. Known in the media as “the Gandhi of Sudan”, Taha was a religious reformer and nationalist leader, a strong advocate of pacifism and the search for alternative political and spiritual paths.

Sudan’s unstable independence process

The last years of Anglo-Egyptian condominium (which lasted from 1898 to 1956) were marked by tension with the South of the country, ethnically and religiously different, with significant majorities of Christian or animist population. It was also characterized by tense debates on the role that Islam should play in the State, confronting the socialist current, the traditionalist Islamic current, associated with the pro-independence elites, and the extensive Sufi presence in the country.

The last years of Anglo-Egyptian condominium (which lasted from 1898 to 1956) were marked by tension with the South of the country, ethnically and religiously different, with significant majorities of Christian or animist population. It was also characterized by tense debates on the role that Islam should play in the State, confronting the socialist current, the traditionalist Islamic current, associated with the pro-independence elites, and the extensive Sufi presence in the country.

Mahmoud Muhammed Taha grew up in this Sufi environment. Born in 1909 in Rufa’a, a small town south of Khartoum on the banks of the Blue Nile, his family was linked to the Qadiriyya branch, one of the three main Sufi orders in the country.

Taha was involved in the nascent Sudanese nationalist movement from its origins in the late 1930s, while studying engineering at what is now the University of Khartoum. Dissatisfied with the opposition to the colonial regime, which he accused of collusion with the settlers, or of links with sectarian traditionalist currents, he founded the Republican Party in 1945[1]. The foundation of this political organization marked the beginning of a few months of confrontation with the British authorities which culminated in Taha’s imprisonment the following year.

After being arrested for the first time in 1945 for the political activity carried out by the Party, Taha led a revolt the following year in his hometown of Rafa’a against the British authorities, on the occasion of the arrest of a woman accused of practicing a form of genital mutilation on her daughter. Despite condemning such practices, Taha believed that banning them would only lead to increased social unrest and the spread of such practices.

His two-year prison sentence marked the beginning of a period of contemplation and spiritual search, which would continue during a three-year period of withdrawal from society. These five years of spiritual reflection would cement the spiritual thought developed by Taha in later years.

Taha’s “path”

Taha summarized this acquired understanding of the Qur’an in 1952 in the book “This is My Way”. This work advocated a direct and personal interpretation of the Qur’an. It also offered a reformist and original vision of religious thought, which proposed the distinction between two types of suras, or azoras, in the Qur’an, according to their content and nature. To this end, he distinguished between the suras revealed during the Prophet’s time in Mecca, before his exile to Medina, and whose content revolves around the regulation of personal devotion (suras of a universal nature). According to Taha, the second group of azoras, revealed in Medina in a context of persecution of the Prophet and his followers and after the Prophet attained a position of political leadership (suras of circumstantial character), reflects a more “defensive” content, with greater references to violence, and is intended for the political and social regulation of the believers[2].

Taha summarized this acquired understanding of the Qur’an in 1952 in the book “This is My Way”. This work advocated a direct and personal interpretation of the Qur’an. It also offered a reformist and original vision of religious thought, which proposed the distinction between two types of suras, or azoras, in the Qur’an, according to their content and nature. To this end, he distinguished between the suras revealed during the Prophet’s time in Mecca, before his exile to Medina, and whose content revolves around the regulation of personal devotion (suras of a universal nature). According to Taha, the second group of azoras, revealed in Medina in a context of persecution of the Prophet and his followers and after the Prophet attained a position of political leadership (suras of circumstantial character), reflects a more “defensive” content, with greater references to violence, and is intended for the political and social regulation of the believers[2].

During this period, Taha began to be referred to as Ustadh, “teacher”, among his followers, a traditional title reflecting the importance of education in Islam, and demonstrating a willingness to transmit and train his followers in a spiritual and social “new way”[3].

In a context of tension and religious pressure for the adoption of the Shari’a after the country’s independence and the strengthening of the Muslim Brotherhood, with a rigorous interpretation of Islam, Taha’s proposal represented a call for moderation and religious freedom, advocating personal interpretation, freedom of belief and the promotion of democracy within the parameters of Islam. After the country’s independence in 1956, this position would be reflected in his rejection of the recognition of Sharia as a legal source in the new Constitution. In his opinion, this recognition could only contribute to increasing the differences between the northern and southern regions and to intensifying discrimination against the non-Muslim population of the southern region[4].

The creation of a spiritual movement and its impact on women

After Sudan’s independence in 1956 and within the framework of the spiritual development of ustadh Taha, his political party, the Republican Party, evolved into a spiritual movement, the Republican Brothers and Sisters, without abandoning their political work or their desire to influence the future of Sudan to ensure a more egalitarian and conflict-free future.

Already in 1955, Taha had published his work Usus Dustur As-Sudan (Foundations for the Constitution of Sudan), a guide of proposals for the future independent Constitution of Sudan, in which he advocated the adoption of a model of a socialist, democratic and federal republic, which would avoid recognizing the Sharia as a principle of law. The following year, he participated in the Constituent Commission in charge of drafting the Constitution, abandoning it precisely because of disagreements over the role to be played by religion.

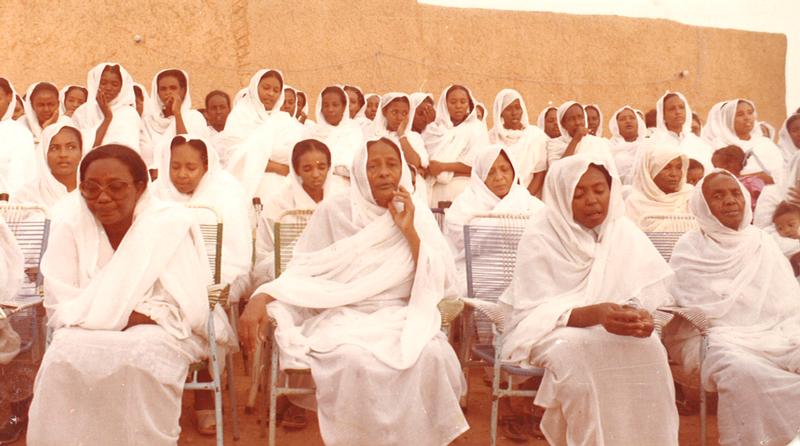

Beyond its political proposal, this movement questioned accepted social customs and mores, advocating a spiritual liberation and social transformation that began within oneself and within the community of Taha’s followers. Thus, the movement advocated the abandonment of the country’s traditional customs, with a special emphasis on the emancipation of women, promoting new practices and customs that would overcome their subordinate position. The movement rejected the guardianship of women as a legal figure, as well as the subordination of women in religious matters, until then relegated to religious practices and rituals. The promotion of women’s equality, socially and spiritually, was reflected in their practice of traditional rituals of social transition (their role in births, marriages, funerals…), in their acquisition of religious knowledge and in their active participation in the activities, debates and rituals of the movement[5].

Although this movement never reached a large number of followers, as it never exceeded several thousand followers, the influence of the Taha ustadhh far exceeded its mobilization capacity, due to its defense of an Islam that embraced human development and democracy as essential components of the faith[6], in a context marked by religious tension.

Political persecution of Republican Brothers and Sisters

A period of increased activity at the end of the 1960s, coinciding with a period of slight political opening, allowed Taha to publish three new works (Tarieq Mohammed -The Way of Mohammed-, Risalat Assalat -The Message of Prayer-, and Arrisala Atthaniya min Al-Islam -The Second Message of Islam-), which deepened his reformist path. This thinking led Taha to be accused of apostasy by several professors of Islamic studies in 1968 and sentenced in absentia. Taha refused to participate in the trial, citing his right to freedom of expression. Although the sentence had no repercussions at the time, it laid the foundation stone for his subsequent persecution and, finally, his execution.

A period of increased activity at the end of the 1960s, coinciding with a period of slight political opening, allowed Taha to publish three new works (Tarieq Mohammed -The Way of Mohammed-, Risalat Assalat -The Message of Prayer-, and Arrisala Atthaniya min Al-Islam -The Second Message of Islam-), which deepened his reformist path. This thinking led Taha to be accused of apostasy by several professors of Islamic studies in 1968 and sentenced in absentia. Taha refused to participate in the trial, citing his right to freedom of expression. Although the sentence had no repercussions at the time, it laid the foundation stone for his subsequent persecution and, finally, his execution.

The coup d’état staged by the Free Officers Movement in 1969, advocates of greater socialist postulates, and the end of the civil war with the South in 1972 brought a moment of greater understanding between the Republicans and the authorities. Despite this, their public activities were banned in 1973. Although its members were not directly persecuted, their capacity for action was severely limited from then on. Despite this, the movement continued to support the government led by the newly installed Jaffaar al-Numeiry throughout the 1970s, as long as the peace agreement with the South was respected and the sharia was not constitutionally adopted.

The situation changed in the early 1980s, when a weakened government began to lean on the increasingly important Muslim Brotherhood, finally agreeing to the adoption of Sharia in 1983. Their open opposition to this decision led to the arrest of several members of the Republicans, including Taha himself, who remained in prison for a year and a half until December of the following year. With their mobilizations, the Republican Brothers and Sisters insisted on the discriminatory consequences that this law would have on the South of the country, and its possible repercussions on the peace process. This date, 1983, coincides, in fact, with the beginning of the second stage of the civil war between the North and the South.

Upon his release from prison, Taha published “This… or the deluge”, a new essay in which he reaffirmed his rejection of the sharia and insisted on its repeal. In this text, he explained:

“Today it is not enough for a citizen to enjoy freedom of worship. He is entitled to the full rights of a citizen in full equality with all other citizens. The rights of the citizens of the south in their country are not provided for in the sharia, but in Islam at the level of the fundamental Koranic revelation.”

Arrested again, Taha was again charged with apostasy and sentenced to death. The sentence was carried out on January 18, 1985, amid major international protests.

A living legacy

His death had important consequences for the an-Nimeiry regime. The sentence had been condemned by an important part of the Sudanese elite, as well as by countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and Egypt, and international associations such as Amnesty International. The regime’s decision to execute the sentence contributed to the weakening of its support both domestically and internationally, and finally culminated in a new military coup d’état in 1989 by Umar Hassan al-Bashir[7].

More importantly, his reformist proposal has prevailed as an example of the promotion of a moderate Islam, in a context of political and religious tension, and for his defense of democracy, citizens’ rights and freedoms, as well as his special emphasis on religious freedom and gender equality.

Alfonso Casani – FUNCI

References

[1] https://www.alfikra.org/page_view_e.php?page_id=2

[2] Tangenes, Gisle (2006). “Culture: the Islamic Gandhi”, Bits of News. https://web.archive.org/web/20070927021918/http:/www.bitsofnews.com/content/view/3856/42%7C

[3] Howard, Stephen (1988). “Mahmoud Mohammed Taha: a remarkable teacher in Sudan”, Northeast African Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1 (1988), pp. 83-93

[4] https://www.alfikra.org/page_view_e.php?page_id=2

[5] Howard, Stephen (2006). “Mahmoud Mohammed Taha and the Republican Sisters: A Movement for Women in Muslim Sudan”, The Ahfad Journal Vol. 23. No. 2

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ortega, Rafael (2019). “Sudán: ¿islam africano e islam árabe? Dicotomías del islam, el islamismo y el sufismo”, Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política, Humanidades y Relaciones Internacionales, año 21, nº 41. Primer semestre de 2019. Pp. 439-464.

No Comments