Tristan Semiond – FUNCI

Nelson Mandela is undoubtedly the best known, and one of the most important figures in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. However, in the path of his legend and resistance, many people, often forgotten, have also marked the rainbow nation’s fight for freedom. This article is a tribute to one of the many people who dedicated his life to the struggle against this racist regime: Imam Haron.

A brief history of the presence of Islam in South Africa

To understand its history, first we need to understand the history of Islam in South Africa. This vast territory located at the southern tip of the African continent has been home to a Muslim minority for several centuries, mainly from the Indian subcontinent and South Asia.

The presence of Muslim communities is largely linked to the colonial history of the country. This allows us to divide the establishment of these communities into three periods:

The first phase corresponds to the arrival of the first Muslims in what was then the Dutch Cape Colony (1652-1795). This arrival occurred in the context of the forced displacement of slaves, prisoners and political exiles by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) from its territories in the Dutch East Indies to its Cape Colony. A key date is 1668, when the VOC – in its attempt to control present-day Malaya – condemned Sheik Matebe Shah, the last Sultan of Malacca, to exile. With his arrival in Cape Town, a new cultural and religious identity began to develop: that of the “Cape Malays”.

Over time, and especially during British rule (1795-1910), the term “Cape Malays” began to encompass the vast majority of Muslims in the region, regardless of their origin. The oldest mosque in the country, Awwal, was built in 1798 in the Bo-Kaap area of Cape Town.

The second phase was characterized by the arrival of laborers from British India (the Culis) who worked mainly in the sugar cane fields of the British colony of Natal (1843-1910). Among these workers, there was a minority of Muslims. They settled in what is now known as the Kwazulu-Natal region, whose capital is Durban.

The third period was marked by the arrival of Muslims from the African continent after the end of apartheid in 1994.

Muslim communities during apartheid

Within the apartheid system, the vast majority of South African Muslims belonged to two groups: the “Coloureds” (this group included people considered to be of “mixed” descent) and the “Indians“. Although people from these two groups had more rights than those considered “Africans“, they were not numerous and, over time, experienced a process of increasing exclusion and repression.

This context led to religious and cultural identity that would have an important role in the mobilization against apartheid. While many movements and organizations began to form and mobilize against this racist system (African National Congress; Pan Africanist Congress; South African Indian Congress; Coloured People’s Congress…), Muslim communities and their representatives, especially in the period from 1950 to 1970, did not want to politicize and organize against Hendrik Verwoerd’s regime.

For example, the Muslim community in Cape Town – with the exception of a small but increasingly politicized youth sector – was deeply influenced by the Muslim Judicial Council (MJC), a judicial and theological body established in 1945. This council was known, at this time, for its conservative positions and a silent, or apolitical, attitude towards the apartheid regime.[1] As long as religious issues and freedom of belief were not jeopardized they saw no need to oppose and politicize.[2]

However, the emergence and emancipation of certain religious figures committed to the struggle against apartheid gradually established the basis for the cultural, social and political engagement of many people from Muslim communities. This is notably the case of Abdullah Haron.

Imam Haron, the voice of an anti-racist and anti-apartheid Islam

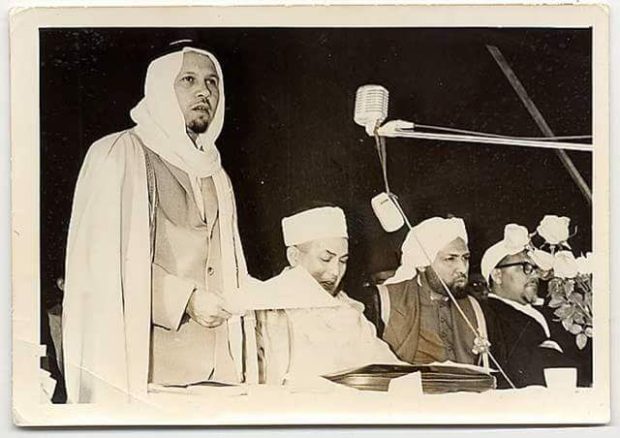

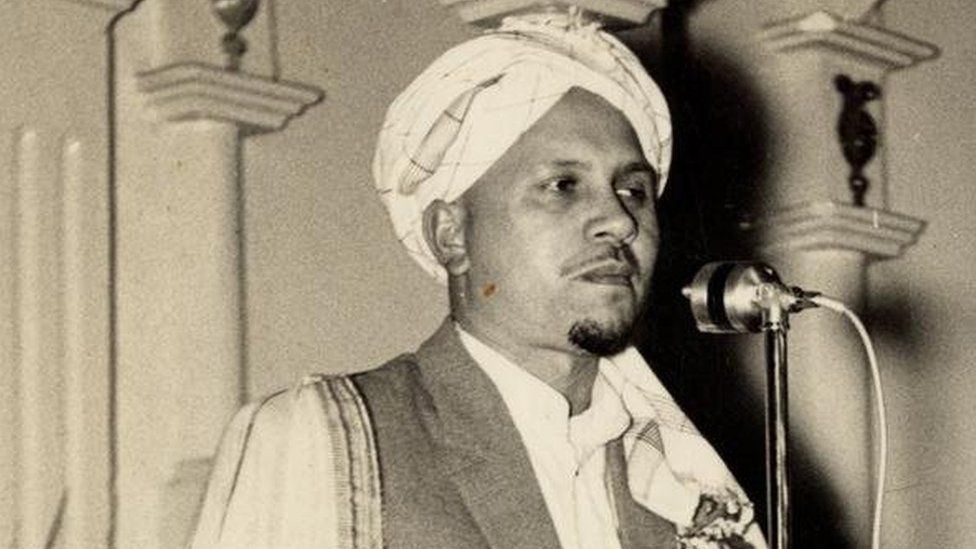

Abdullah Haron was one of the youngest imams in South Africa, only 32 years old when, in 1955, he was appointed as imam to lead the congregation of the Al-Jamia Mosque in Claremont (Cape Town).[3] This position allowed him to put many of his ideas into action, and he quickly became the symbol and icon of the Muslim community that opposed the struggle against apartheid.

It was in his sermons and lectures that he began to criticize the barbarity and inhumanity of racial laws, arguing that they did not respect many of the fundamental values and messages intrinsic to Islam. In fact, Prophet Muhammad is considered by many as an anti-racist role model.

Among others stands out the sermon prepared after the start of the march organized by the Pan-African Congress in Cape Town in 1960, in which he stressed the importance of the concept of human brotherhood in Islam[4].

A social commitment based on the importance of education

Several aspects of his commitment and legacy deserve to be highlighted, such as his fight for education and the importance he gave to the youth.

Several aspects of his commitment and legacy deserve to be highlighted, such as his fight for education and the importance he gave to the youth.

Education, in particular, always played a key role as an engine of change. He established, for example, evening classes in which he taught Arabic to members of the community so that they would not simply memorize surahs from the Qu’ran without knowing the meaning of the words.

In addition, when he led Friday prayers ( صَلَاة ٱلْجُمُعَة, Jumu’ah), he used to take the opportunity to organize spaces for discussion after the prayer, leaving the choice of topics to the younger participants. He also distinguished himself by inviting women to participate in his classes and in these debates. In the same framework, he also invited people from outside the Muslim community to speak to the young people about the socio-political situation in the country.[5]

The Claremont Muslim Youth Association (CMYA) in 1958 allowed him to broaden this latter purpose. Through this association, the youth of the Claremont neighborhood met many (non)Muslim thinkers and political activists of the time who came expressly to speak to their community. These discussions allowed both the imam and the CMYA youth to open up their perspectives and opinions on contemporary problems in the country and possible solutions. These exchanges also helped the Claremont youth to formulate their own ideas about Islam and society, moving away from the familiar conservatism.

These actions reflect the importance that social engagement had for Imam Haron. In fact, he was the only imam in Cape Town who refused to receive remuneration for his services, as he did not consider it necessary because he worked as a sales representative for the Wilson Rowntree candy company. Moreover, his work allowed him to develop important links with the “Africans” communities in Cape Town and with some liberation movements, such as the African National Congress (ANC) or the PAC, because he had a permit to legally enter and leave these areas.

An increasingly important commitment over the years

Indeed, in 1950 the Group Area Act prevented people of different “races” from meeting and mixing by assigning exclusive occupancy zones to specific “racial groups”. In this regard, he was one of the few Muslims of his time (most of whom belonged to the “Coloured” or “Indian” group) who regularly visited other townships of the African community, such as Nyanga and Langa. His presence illustrates both his social commitment and his willingness to fight against racism.

In 1965, he was himself affected by this law when he was forced to move from his family home to another neighborhood for colored people in Athlone.

He delivered several speeches and sermons criticizing the Group Area Act, including a famous speech at the Drill Hall in Cape Town on May 7, 1961, in which he called the Act “inhuman, barbaric and un-Islamic” and added that “these laws were a complete negation on the fundamental principles of Islam… (they are) designed to cripple us educationally, politically and economically… We cannot accept (this type of) enslavement.”[6]

In this way, he also played an important role in the anti-apartheid movements, supporting both victims and organizations by raising funds or organizing courier and shelter services.

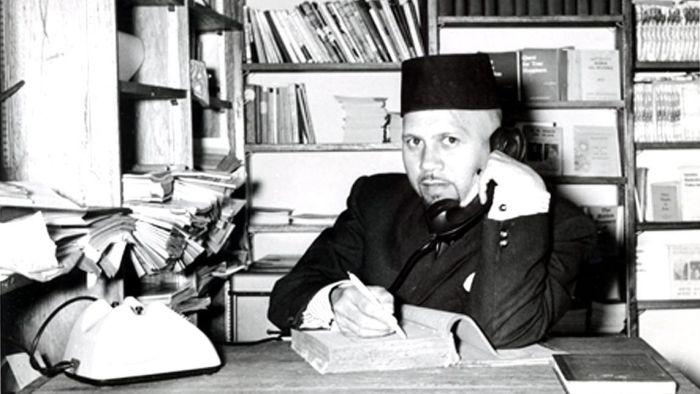

He was also one of the founders and a member of the editorial board of Muslim News in 1960, the first Muslim newspaper in the country.[7] On March 31, 1961, together with other members of the South African Muslim community, he launched the famous anti-apartheid pamphlet “Call of Islam“. The main objective was to protest against the status-quo in the face of the implementation of the Group Area Act and other racist apartheid laws:

“We can no longer tolerate further encroachment on these our basic rights and therefore we stand firm with our brothers in fighting the evil monster that is about to devour us – that is, oppression, tyranny and baasskap[8]. […] Therefore, we hereby declare for everyone to know that we solemnly pledge ourselves to fight against all the injustices on the basis as ordained by Almighty Allah.”[9]

One last period abroad before his death

Subsequently, between 1966 and the end of 1968 he made a pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj). This trip was also an opportunity to travel, secretly, to Egypt and Europe, in order to defend the cause of the entire oppressed South African population. To this end, he made contact with the World Islamic Council, some representatives of Arab countries, but also with political exiles from the ANC and PAC. These meetings allowed him to provide information on the socio-political situation, but also to collect money to distribute upon his return.

After his secret trip to Egypt, Abdullah Haron stopped in London, where his eldest daughter, Shamela, was studying. During his stay, he met Canon John Collins of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. This Anglican priest was dedicated to raising money for the families of political prisoners, exiles and refugees or murdered. It seems that the two men became friends.

A martyr to the struggle for freedom celebrated across borders and differences

However, his speeches and activities seeking unity and rapprochement made him a major threat to an increasingly brutal system whose motto was “divide to rule”.

He returned from London knowing that his life, or at least his freedom, was in danger and that he was under surveillance by the South African Police (SAP) and its Special Task Force (STF). On his return he was not spared from the repressive machinery of the apartheid police, and on May 28, 1969 he was arrested and imprisoned. He would never see the light of day again, as after 123 days of solitary confinement, interrogation and probably torture, he died in detention on September 27, 1969. The police, of course, denied any responsibility for his death, attributing it to an unfortunate fall down the stairs.

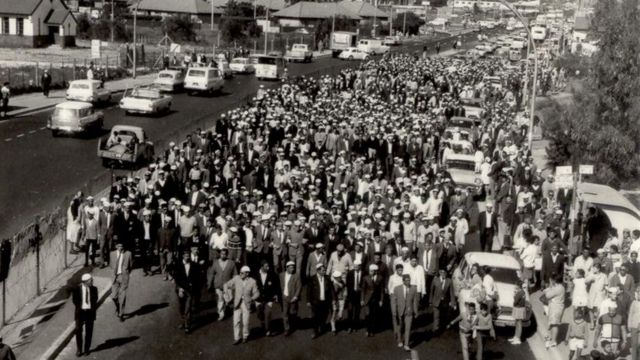

He was the first cleric of any faith to die in detention under apartheid, showing that no one was safe from these racist and supremacist policies. However, on September 29, some 40,000 people attended his funeral and the march to the Muslim cemetery in Mowbray, paying the greatest possible tribute to this freedom and humanity hero.

There were other tributes and his friendship with John Collins was illustrated a few days after his death when the latter celebrated a mass in his name on October 6, 1969, during which he paid tribute to him as a martyr and recalled his great openness and deep tolerance. He was thus the first Muslim to be commemorated in London’s famous St. Paul’s Cathedral.[10]

His life and death were also summed up by Victor Wessels, professor and Marxist, who said at his funeral: “He died not only for the Muslims. He died for his cause, the cause of the oppressed people.”[11]

Haron was posthumously awarded the Golden Luthuli Order in 2014 for his “exceptional contribution to raising awareness of political injustices.” On September 9, 2019, the Stegman Road Mosque and his grave were officially declared a provincial heritage site in honor of his memory and contribution to the struggle for freedom and democracy.

References

[1] Günther, Ursula. “The memory of Imam Haron in consolidating Muslim resistance in the Apartheid struggle”, Journal for the Study of Religion, vol.17, no. 1, 2004, pp.117-150.

[2] Ibid.

[3]Abdullah Haron: l’imam décédé en combattant l’apartheid en Afrique du Sud. BBC News Afrique. 01/10/2019. https://www.bbc.com/afrique/region-49894833

[4] «Abdullah Imam Haron». South African History Online. 17/02/2011 (actualizado el 02/10/2020).https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/imam-abdullah-haron

[5] Abdullah Haron: l’imam décédé en combattant l’apartheid en Afrique du Sud. BBC News Afrique. 01/10/2019. https://www.bbc.com/afrique/region-49894833

[6] «Abdullah Imam Haron». South African History Online. 17/02/2011 (actualizado el 02/10/2020).https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/imam-abdullah-haron

[7] Günther, Ursula. “The memory of Imam Haron in consolidating Muslim resistance in the Apartheid struggle”, Journal for the Study of Religion, vol.17, no. 1, 2004, pp.117-150.

[8] It is an Afrikaans term that refers to the white supremacist policy of apartheid.

[9] “Call of Islam, 31 de marzo de 1961” citado en: (27/06/2020). This Imam Died Fighting Racism. IlmFeed.com. https://ilmfeed.com/this-imam-died-fighting-racism/

[10] Abdullah Haron: l’imam décédé en combattant l’apartheid en Afrique du Sud. BBC News Afrique. 01/10/2019. https://www.bbc.com/afrique/region-49894833

[11] Abdullah Haron: l’imam décédé en combattant l’apartheid en Afrique du Sud. BBC News Afrique. 01/10/2019. https://www.bbc.com/afrique/region-49894833

No Comments