In this article, originally published in Open Democracy, Corinne Torrekens, professor of political science at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, reflects on the rise of Islamophobia in Belgium and the main elements and arguments on which this discriminatory trend relies.

A recent manhunt for an armed Belgian military officer, who had threatened a prominent health expert and was suspected of preparing an attack against a mosque, revealed much about the rise of the radical Right in Belgium.

The soldier, who was deployed in operations in Afghanistan several times between 2011 and 2017, was finally found dead last month, after weeks on the run. In just a few days, a Facebook group supporting the man gathered more than 50,000 members before being deleted by the social network. One of the slogans on the page was: “The one who dares to say out loud what we think”.

Extreme Right discourses are on the rise in Belgium, especially in the Flemish-speaking part of the country, where the region’s extreme Right political party, Vlaams Belang, represents about 20% of votes.

In 2017, Theo Francken, the then state secretary for asylum and migration and a member of the nationalist party, New Flemish Alliance, published a poll about the Mediterranean sea rescue operations towards migrants on his Twitter account, before deleting it a couple of hours later. A vast majority of those who voted (approximatively 900 out of 1,000) chose to exclude Muslim castaways from rescue efforts. Polls showed his hardline stance on migration made him popular with voters but also caused the government coalition to split.

Indeed, a few weeks earlier, a poll indicated that 74% of Belgians viewed Islam as an intolerant religion, 60% saw it as a threat, 43% thought that being both Belgian and Muslim was incompatible and 40% thought Muslims had something to do with terrorism.

Restrictions on Muslims

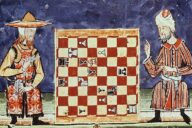

Belgium has already experienced more than three decades of public debates around the integration of Islam itself and Muslims. Even though it may be difficult to assess the impact of such debates, what can be noticed, however, is that they have broken the barriers of what can be said in the public arena about Islam itself, and Muslims. Most of these comments focus on the public visibility of Islam and religious practices and have led to government restrictions on Muslims.

The veil is certainly the most common topic and the first to have emerged in the public debates. The arguments about it range from perceiving it as a symbol of Islamism and female submission, or on the contrary, as a symbol of agency and a public expression of faith. The arguments around it arise frequently, especially in the context of higher education and employment in public administration.

In 2012, the Constitutional Court confirmed the ban on the full-face veil after two rounds of parliamentary discussions where – quite ironically – deputies went so far as to quote Quranic verses to demonstrate the fact that it was not a religious obligation.

The religion of Islam and Muslims themselves are regularly assigned negative cultural values

In 2015, a Belgian company was granted a halal certification for its product – a well-known Belgian delicacy called “Liège syrup”, made of sugar, apple and pear juice – in order to export it to Indonesia. In response, a local politician returned his can of syrup to the company, claiming it was a “treason of our traditions” and that he would never eat it again even though no ingredients had been changed in the syrup for it to be deemed halal. The Senate president Christine Defraigne said she understood the uneasiness over this certification since “it reveals a submission to a cultural label which is not ours”.

In 2017, two regions (Flanders and Wallonia) of the complicated country that is Belgium decided to ban the ritual slaughtering that had been allowed under certain conditions and sometimes raised issues around organisation, traceability and suffering.

The main argument mobilised during this debate was that of animal wellbeing, with claims that ritual slaughtering is much more painful than non-ritual, despite ritual slaughtering only representing around 20% of all slaughtering and despite the many videos filmed by animal activists showing the hardship of animals in non-ritual slaughterhouses.

Opposed to a Belgian identity

What is clear from these debates is how the religion of Islam and Muslims themselves are regularly assigned negative cultural values (oppressive, barbarian, violent, illiberal etc.) and opposed to a naturally tolerant ‘Belgian’ identity.

In this context, over more than two decades, Islamist terrorist attacks have come to personify the threat of a new Trojan horse and the division between “us” (autochthonous non-Muslim Belgians), and “them” (those from a foreign and Muslim background).

As an example of this, a few days after the terrorist attacks of 22 March 2016, when three suicide bombings killed 32 people in Brussels Airport and a metro station in the city, Jan Jambon, the then deputy prime minister (now prime minister) and member of New Flemish Alliance, claimed that a “significant part of Muslims danced in the streets after the attacks” without any proof of his allegations.

Such an extreme Right-wing political discourse does not yet exist in the French-speaking part of the country but there too, the political debate surrounding Islam and Muslims is also deteriorating. The same as in France and the Netherlands, academics developing nuanced analysis are harassed and insulted on social media and, more importantly, are accused of playing into the hands of Islamists.

Freedom of expression is a core principle of liberal democracies and public debates have never meant consensus. However, the current degree of polarisation around Islam and Muslims – which has led not only to a lack of civility but also to threats of violence – undermines the very idea of public debate itself.

Source: Open Democracy

No Comments