Tristan Semiond – FUNCI

In a first article, we showed how madrasas have played a fundamental role in the democratization of education and knowledge in the Islamic world, inspiring, in this way, the rest of the world.[1] We also saw how this historical institution has been transformed over time, adapting to its contexts, its geographical positions, and the main socio-political and religious actors of each era.

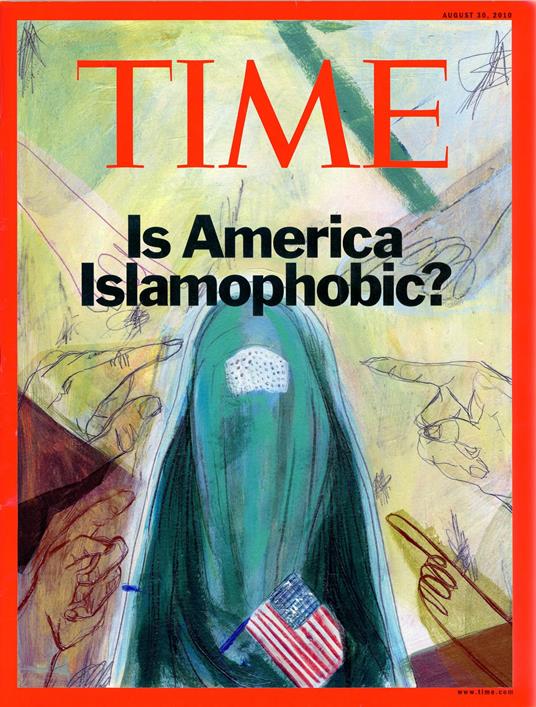

However, if madrasas were once considered as a reference model, we have now moved away from this vision, in a context marked by the rise of Islamophobia. In this second article, we will try to understand how the image of madrasas has been radically transformed in the collective imagination, from a center of knowledge to a supposed place of obscurantism.

For this purpose, it is necessary to deconstruct Islamophobic and essentialist views that link madrasas to places of radicalization and affiliation to terrorism, studying them through a more constructivist vision.

Madrasas in the post 9/11 world

Since the terrible attacks of September 11, 2001 in New York, and even though none of the alleged attackers to the Twin Towers were from Pakistan or had studied in a madrasa, these institutions received world-wide attention as “centers of religious militancy and radicalism”.[2]

As part of president G.W. Bush’s “Greater Middle East” [3] democratization strategy, the Western media (as well as the governments of some countries) developed a narrative linking madrasas to terrorism and calling for their reform and “modernization” to combat this violent activity.

Syed Vali Nasr, an Iranian-American researcher and historian, summarized this phenomenon in the following way:

“The violent attack of 9/11 convinced the Western world especially Americans that the problem with the Muslim world is that it is ‘unenlightened’ which means that it is pre-Renaissance in its mindset. Due to their own historical experience many perceived that the Islamic world is in need of a Religious Reformation. Islamic Madrasas were perceived as the places where traditional, obsolete teachings indoctrinate dangerous values to the young minds”[4]

These discourses go beyond the traditional rhetoric of opposition between an East with medieval institutions and a superior and “enlightened” West – a clearly orientalist vision -, as they clearly identifies these institutions as the cause and origin of terrorism.

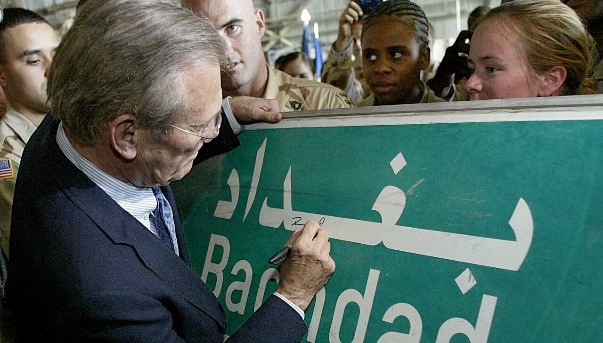

In a memo leaked to the media in October 2003, Donald Rumsfeld, the US Secretary of Defense, stated:

“Are we capturing, killing or deterring and dissuading more terrorists every day than the madrasas and the radical clerics are recruiting, training and deploying against us?”[5]

Initial perceptions of Pakistani madrassas, based on a desperate search for the causes of the 9/11 attack, led to hasty and oversimplified conclusions.

A reality quite different from hegemonic discourse

Initial perceptions of Pakistani madrassas, based on a desperate search for the causes of the 9/11 attack, led to hasty and oversimplified conclusions.

However, this narrative gradually began to lose credibility as some researchers – less politicized and more objective – revealed new facts based on diverse social realities that did not fit these generalizations.

This is the case of the research carried out in 2006 by Peter Bergen and Swati Pandey and published in the Washington Quarterly of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. The report covers the case of 79 terrorists responsible for the following five terrorist attacks: the World Trade Center in 1993; the attacks on the US embassies in Africa on August 7, 1998 (Nairobi and Dar es Salaam); the 9/11 attack; the Bali nightclub bombing in 2002; and the London bombing of July 7, 2005.

The study found that the vast majority of the perpetrators of these attacks had not studied or visited a madrasa, while 27% had attended Western schools/universities.[6]

Moreover, the research highlighted the importance of Western academic training in a terrorist’s journey. They have therefore raised questions about the type of education that can contribute to terrorism, and madrasas do not seem to be one of them:

“Madrasas are less closely correlated with producing terrorists than are Western colleges, where students from abroad may feel alienated or oppressed and may turn toward militant Islam.”[7]

This last argument is also defended by other researchers such as Dr. Marc Sageman (former CIA operations officer).

Over time, many research projects have challenged the initial theory, presenting alternative stories and realities. This shift in Western understanding of madrasa education has raised new questions about this institution and the correct way to study it or to think of solutions to existing problems.

Despite this, nowadays, public opinion has not changed that much, and this discourse continues to feed other simplistic or Islamophobic ideologies and thoughts, such as that of a “clash of civilizations” or a “culture war”.

The consequences of a reductionist narrative

The Yale Center for the Study of Globalization conducted a study on the bias of the US media coverage of Pakistani madrassas since 9/11.[8] The research shows that the majority of articles were written in such a way that whenever madrasas were mentioned, readers intuitively inferred that all these schools were anti-American, anti-Western and pro-terrorist centers.

Such media coverage leads to a serious manipulation of public opinion in favor of the “clash of civilizations” theories, participating in a process of othering Islam and increasing Islamophobia. Moreover, this story is part of a political instrumentalization that, at the time, aimed to justify the American military intervention in Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq. The argument used referred to a hypothetical fight against terrorism rooted in the madrasas.

Such media coverage leads to a serious manipulation of public opinion in favor of the “clash of civilizations” theories, participating in a process of othering Islam and increasing Islamophobia. Moreover, this story is part of a political instrumentalization that, at the time, aimed to justify the American military intervention in Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq. The argument used referred to a hypothetical fight against terrorism rooted in the madrasas.

As Gramsci reflects in his conceptual development of cultural hegemony, media producing discourses and official narratives must be understood as instruments of the dominant (hegemonic) group to impose its vision of a complex situation, in order to promote consensus within society and legitimize its political decisions. In this vein, the official Western narrative, close to the U.S. position, portrayed Islamic education as a medieval and violent phenomenon in need of reform, a discourse that strongly influenced Western public opinion to legitimize the policy of interference promoted.

Institutions resulting from their socio-political contexts

However, madrasas should not be analyzed as fixed and “timeless” institutions, but rather as “products of their time”[9], marked by an important diversity, because of their geographical location, contexts, as well as the actors involved.

In this context, it should not be forgotten that today’s madrasas are largely a product of the colonial era, since they were built and developed under European imperialism, which controlled most of the Muslim-majority territories between the end of the 19th century and the mid-20th century.

The influence of Western modernity, both through colonial policies and the modernization of the Ottoman Empire, profoundly changed the organization and the way of studying in the madrasas[10], as explained in the previous article.

Madrasas have not only adapted to colonization, but also to other global changes such as globalization and the rise of transnational experiences, welcoming students from all backgrounds, or more recently adapting to new technologies.

Geopolitical contexts have also brought about many changes, and unfortunately, one of them is the development of more radical discourses in the madrasas, as illustrated in a 2002 report by the International Crisis Group on Pakistani madrasas.

This report explains the evolution of madrassas in Pakistan especially since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (1979-1989). Indeed, this invasion marked a turning point in the development of madrassas in the region. It led to an increase in the number of madrasas in Afghanistan and Pakistan, a fact that the report certainly links to the jihad against the Soviets. However, it also shows that violence does not originate in madrasas and that the vast majority of madrasas have never advocated it. The number of madrassas linked to violence was therefore very small and never showed direct involvement, but rather an ideological influence.[11]

Another interesting fact reflected in the report is the importance of the United States in promoting jihadist culture in Pakistani and Afghani madrasas during the 1980s. To illustrate this, the investigation cites several speeches, reports, and official documents from the CIA, as well as from Pakistani intelligence services, that urged participation in the “holy war” and presented it as a sacred duty. These narratives were part of a propaganda campaign. Books were published in Pashto and Dari by the Center for Afghan Studies at the University of Nebraska-Omaha and funded by USAID, in which American and Afghan experts encouraged young Afghans to participate in jihad. For example, math was taught by counting dead Russians and Kalashinkovs.[12] Between 1984 and 1994, the University of Nebraska received $54 million USD for this project, and 13 million copies were distributed to Afghan refugee camps and Pakistani madrasas.[13] These books were also useful for the Taliban, future enemies of their main sponsors.

The International Crisis Group report admits that traditional madrasa texts did not usually include militant and violent content legitimizing jihad before the American policy of containment was promoted.

The International Crisis Group report admits that traditional madrasa texts did not usually include militant and violent content legitimizing jihad before the American policy of containment was promoted. Therefore, this propaganda has directly influenced the development of radical discourses within the madrasas of the region. It is these same discourses and rhetoric that is now being denounced by American politicians as an Islam and Muslims intrinsic problem.

If radicalization within some madrasas is an undeniable fact, it should be analyzed as a social phenomenon not isolated from its contexts, rather than treating madrasas as if they were a homogeneous block in which radical discourse is the norm.

Madrasas are, by definition, part of a specific historical, social, and political situation that they help shape as institutions of knowledge production. The diversity of contexts means that madrasas differ from one Muslim country to another. All societies have undergone profound multidimensional changes in recent decades, and the impact of these socioeconomic and political transformations has had a significant impact on madrasas, as well as on a centuries-old public education system. Having become mass educational institutions, they have had to adapt to the many challenges of each society and thus reflect, to a large extent, a tendency to fit the general model of public education, in terms of curricula, classrooms, scholarships, etc.

Promoters of the democratization of education

In contrast to simplistic and essentialist discourses, it is important to emphasize that madrasas are important actors in the democratization of education in some countries characterized by inefficient education systems and the absence of universal public education.[14] From this perspective, the madrasa is not a medieval institution, but a place of connection with the globalized world through the teaching of English, computers, audiovisuals, etc.[15]

In contrast to simplistic and essentialist discourses, it is important to emphasize that madrasas are important actors in the democratization of education in some countries characterized by inefficient education systems and the absence of universal public education.[14] From this perspective, the madrasa is not a medieval institution, but a place of connection with the globalized world through the teaching of English, computers, audiovisuals, etc.[15]

We can take the example of the role of the madrasas in Narapatipara – West Bengal, India – which permits us to deconstruct all the clichés surrounding this institution.

One of its directors, Mohammad Sattar Ali Mondal, explains in an interview with the BBC that the students of his madrasa ” have the same syllabus, the same curriculum, the same management, the same appointment of teachers, both Hindus and Muslims, same pensions, benefits and pay. Everything is the same“[16]. The difference lies on the greater emphasis on Islamic studies.

This madrasa is part of the West Bengal Board of Madrasa Education (WBBME), in which over 500 madrasas are registered. They are distinguished by the fact that they include not only Muslims, but also Hindu’s students. When some people questioned if the WBBME madrasas should be considered as madrasas in the original and traditional sense of the word, Mohammad Sattar responds:

“Madrassa is an Arabic word and means educational institution. In Bengali, its known as Shiksha Pratisthan, in English, its called school, in Hindi, Vidyalaya and in Sanskrit, toll. […] It comes down to the question of what each individual school wants to teach its pupils” [17]

According to the director, the important thing is to preserve the culture, the traditions and the use of the Arabic language but also providing the children with an education and a curriculum that will allow them to be sufficiently prepared for the 21st century society and thus have the necessary training to have professional and social opportunities.

In conclusion, madrasas should not be seen as identity-based particularisms or as the remains of a medieval Muslim world, but rather as an experience of openness and perpetual adaptation to the world. This process of adaptation has forced these institutions to confront the social, cultural, and confessional pluralism that characterizes all societies today. This can lead to conflicts, whihc might result in some sort of radicalism, but at the same time, it fosters competition between institutions and ideas, fostering pluralism in the education field as a whole.

The above examples show that the systematic assimilation of madrasas with radicalism and terrorism is not only a mistake, but it also feeds the ideas of a supposed “clash of civilizations”, therefore oversimplifying a more complex social phenomena.

It should not be forgotten that madrasas, now and in the past, have been involved in the religious but also secular training and education of millions of children in the Maghreb, the Middle East, Anatolia, Africa and Central and East Asia.

[1] George Makdisi (1984) “The Rise of Colleges. Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 104, No. 3. pp. 586-588

[2] Sajjad, Fatima. “Reforming madrasa education in Pakistan: Post 9/11 perspectives.” Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization , no. 1 (2013): 104–121

[3] Adelkhah, Fariba. Sakurai Keiko. « Les madrasas chiites afghanes à l’aune iranienne : anthropologie d’une dépendance religieuse » Les études du CERI n°173, janvier 2011.

[4] Syed Vali Nasr, The Rise of Sunni Militancy in Pakistan: the Changing role of Islamism and the Ulama in Society and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

[5] As cited in: Sajjad, Fatima. “Reforming madrasa education in Pakistan: Post 9/11 perspectives.” Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization, no. 1 (2013) p.107-108

[6] Peter Bergen and Swati Pandey. “The Madrassa Scapegoat” The Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Massachusetts, institute of Technology, 2006. pp. 117–125.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Moeller, Susan (2007-06-21). “Jumping on the US Bandwagon for a “War on Terror””. YaleGlobal Online. Yale Center for the Study of Globalization.

[9] Mervin, Sabrina. « ROBERT W. HEFNER, MUHAMMAD QASIM ZAMAN (eds) Schooling Islam : The Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim Education, Princeton University Press, 2006, 278 pages. », Critique internationale, vol. 40, no. 3, 2008, pp. 165-168.

[10] Arshad Alam. “Understanding Madrasas” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 38, No. 22 (May 31 – Jun. 6, 2003), pp. 2123-2126

[11] International Crisis Group Pakistan; Madrasa, Extremism and the Military. Asia Report No.36, (29 July, 2002)

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Adelkhah, Fariba. Sakurai Keiko. « Les madrasas chiites afghanes à l’aune iranienne : anthropologie d’une dépendance religieuse » Les études du CERI n°173, janvier 2011

[15] Ibid.

[16] Sunita Nahar. “What role for madrassas that teach Hindus?”, BBC News, 31/03/2006.

[17] Ibid.

No Comments