Tristan Semiond – FUNCI

Since the September 11 attacks, the assimilation between Islam and terrorism or Islam and violence became part of the media-political discourse in many Western countries, as well as of the collective imagination. This assimilation is linked to the existence of a certain number of prejudices and preconceived ideas about Islam, as well as a certain instrumentalization of them.

These prejudices are in many cases the result of ignorance and excessive media coverage of radical Islam, which gives rise to fears and misunderstandings. This tendency means that many words, notions, or concepts are misused, such as jihad, salafism, sharia, or madrasa… This misuse fosters fear and feeds a discourse of division sought by all extremes. A work of deconstruction and awareness raising on this issue is essential to build bridges between people and fight against ignorance that can lead to fear and hatred.

One of the notions that is often assimilated to extremism and terrorism is madrasa. In two articles, we will try to clarify, first, what this notion has meant in history and its evolutions; while a second article will be devoted to deconstructing the biases that abound in current orientalist and essentialist discourses.

The madrasa (مَدْرَسَة) a historical place of education

Since the revelation of the Qur’an to the Prophet Muhammad, education has always occupied a central place in the Islamic tradition. In fact, the first word of the archangel Gabriel to the prophet was iqrâ, “read”. Since then, one of the first stages of teaching the Qur’ân was reading aloud (qirâ’a), which played a fundamental role in the methods of transmitting knowledge, memorization, and learning. That is why education and its associated places have always been an important pillar of Muslim societies.

In the early days of Islam, mosques were the main places of learning, where Islamic law (fiqh) began to be taught.

In the early days of Islam, mosques were the main places of learning, where Islamic law (fiqh) began to be taught. Fiqh study was based on the two great auxiliary sciences of Quranic exegesis: tafsir, and the science of hadith.[1] The mosque of Medina, created by the Prophet in the 7th century, is in fact considered the first educational institution in the Muslim world. Subsequently the first and most important mosques, such as the Great Mosque of Damascus or the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Cairo, began to have separate rooms solely dedicated to teaching. However, at that time, there was no institution dedicated exclusively to education.[2]

It was not until the end of the 10th century that the creation of specialized teaching institutions, the madrasas, began.[3] In Arabic the word madrasa (مَدْرَسَة) literally means a place of learning. However, as we will see below, this institution has developed primarily as a religious school. We think that the madrasa model first appeared in the private sphere, in teachers’ houses, where scholars taught a few privileged people.

Between thirst for knowledge and politico-religious power

It was during the time of the Seljuk sultanate (1037-1194), under the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad (750-1298), that the golden age of madrasas began, when these institutions began to establish themselves in the public space.

The leap of the madrasas from the private sphere to the public sphere occurred during the reign of the vizier Nizam al-Mulk (1018-1092)[4]. The vizier and scholar – known to be a great politician – advocated the use of these schools as an instrument that would permit the elites to supervise education, especially religious education, in a context of fighting Shiism and crusades. To this end, he transformed the madrasas into state institutions called the niẓāmiya, of which the first and most important was the one in Baghdad.

Nizam built them certainly to develop knowledge, but also to counter the Shiite Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171) and thus strengthen the Seljuk sultanate by spreading Sunni – more specifically Shafiite – ideas through intellectual and educational means. This strategy was also employed by the Fatimids to promote the ideas of Ismailism.

The conquests of Sultan Alp Arslan (1064-1072) enabled the spread of the niẓāmiya in cities ranging from Mesopotamia to Greater Khorasan through a large part of Anatolia by the end of the 11th century.[5]

The creation of these public madrasas by the Seljuq and Fatimid sultans marked a real turning point in the Islamic educational system. These institutions began to teach both the sciences of the Islamic tradition and the rational sciences such as logic, geometry, astronomy, the science of bodies, among others, contributing to the development of the Golden Age of the Islamic world.

The madrasas admitted only the most renowned professors, which is why they had such a good quality of teaching that they were famous as far as Europe, where, according to the researcher George Makdisi,[6] they had a certain influence on the development of the European universities. Notorious scholars and theologians of the Islamic world taught in them, such as Al-Ghazali in the Nizamiyya madrasa of Baghdad.[7]

Politicians and important people followed the step opened by Nizam, building other madrasas with the aim of supporting the dissemination of the ideas of their Madhab[8]. This dimension was one of the reasons for madrasa rapid development, an idea that Foucault would later support by relating the production of knowledge and power: “There is no exercise of power without a certain economy of the discourses of truth that operate in, from, and through that power“.

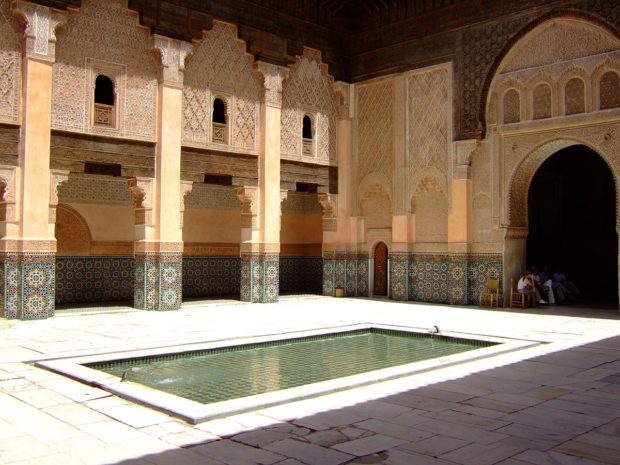

However, we cannot reduce madrasas to a place of political instrumentalization. It was, for example, in the 12th century that the architecture of the madrasas began to be recognizable and to mark the region for its beauty. They were characterized by their wide courtyards and central ponds, as well as by their entrances which were majestic iwans (spaces enclosed only on three sides, generally vaulted), while the dormitories were systematically located in the corners.[9]

For example, one of the last Abbasid caliphs, Al-Mustansir, marked history by building a madrasa – which can still be visited in Baghdad – the Mustansiriya. This example perfectly symbolizes the importance of education and these institutions in an era of intellectual effervescence[10].

Madrasas were not only centres of education and culture, but also housed the “mustahiqs” (students), who received room and board during their studies and ended up sharing their knowledge and experience with future generations. They thus played a very important role in democratizing education by making it more accessible to people from the lower social classes.

Madrasas were also considered “sacred spaces” in which the teacher-student relationship was more important than the institution itself. To this end, the method of teaching in madrasas was largely informal and the curriculum tended to be quite flexible. Depending on the type of madrasa, the emphasis was more on the sciences of the day/time – secular – or on the classical sciences – religious.

It is partly due to them that, during the Golden Age (from the 8th to the 13th century)[11], the territories under the caliphate experienced an important growth in the literacy of the population. In fact, they contributed to a certain democratization of education, and many works have shown that the caliphate had at this time the highest literacy rate of the Middle Ages, in addition to gathering the most important scientists.[12] Although this golden age ended in the 13th century with the Mongol invasions, the madrasas did not disappear and adapted to their new times, showing a great permeability to their context.

Independence and multiplication of madrasas

One of the most important changes took place under the Mamluk sultanate of Egypt (1250-1517) when many of the rulers or dignitaries began to found madrasas through a religious donation in usufruct in perpetuity, known as waqf. Madrasas ceased, then, to be built as the result of public policy, and began to be a symbol of status and power, as well as an effective means of transmitting wealth, social status, and knowledge in Mamluk society.[13]

The capital of the sultanate, Cairo, became the leading city in the revival of Arab science in the 13th and 14th centuries. It is no coincidence that in the 14th century it was also the city with the highest concentration of madrasas.[14] We can affirm that the multiplication of madrasas went hand in hand with intellectual flourishing, as this quote from the scholar Ibn Khaldun shows: “Cairo: metropolis of the world, garden of the universe, meeting place of nations, human anthill, high place of Islam, seat of power. Countless palaces rise there; madrasas flourish everywhere; like shining stars, scholars shine there.”[15]

The dynasty of the madrasas: the Marinid Sultanate

The late 13th century saw the development of madrasas by the Marinid dynasty (1269-1464), which was based in present-day Morocco. The madrasas became an important element of the Marinid art and a central institution in the teaching and politico-religious power that underpinned the dynasty.

At the beginning of the 13th century, several tribes of the Imazighen zenate confederation (according to Ibn Khaldun, one of the three great Imazighen confederations of the Middle Ages, along with the Masmuda and Sanhaya) took advantage of the weakening of the Almohad Caliphate to extend their political power across the region. After taking control of the Rif and Gharb regions, they occupied the city of Marrakech in 1269, the capital of the last Almohad caliph, al-Wathiq. However, the Marinids did not establish their power in Marrakesh but founded a new capital, Fez el-Jedid (Fez the New).

The Marinids have gone down in history as the “dynasty of the madrasas”, leaving an important cultural and artistic heritage present in many cities of Morocco. The Marinid power was also marked by a return to Malikism as a religious doctrine, but also as a source of legitimacy for the new religious and legal elites. Through the construction of madrasas, Fez became – just as Cairo – a hub of knowledge, hosting numerous scholars and jurists, such as al-Wansharisi.

The city of Fez still preserves to this day seven madrasas from the Marinid period, which are remarkable both for their beauty and for the historical role they played. The oldest of the seven madrasas is the Madrasa of Saffarin in Fez el-Bali, built in 1271 on the commission of Sultan Abu Ya’qub Yusuf. Its layout and design showcase the early model of the Marinid madrasas, which developed later in the first half of the 14th century. The choice of the location of this madrasa was not accidental. On the contrary, it was built very close to the University of Qarawiyyin (built in 859 during the reign of the Idrisid dynasty by Fatima al-Fihri). The madrasa played an important role in supporting the university by providing accommodation for the students, while most of the lectures took place at the Qarawiyyin.

This is also the case of the Attarin Madrasa, founded in 1325 by order of Sultan Abu Sa’id Uthman II. This madrasa was intended for the training of high-ranking Merinid officials and it is considered one of the main wonders of Fez. Its exterior is completely plain, but its interior shows a sophisticated decoration, employing many of the materials that characterized the Marinid art, such as wood, stucco, and bronze.

Many of the madrasas were also built near the great mosques, such as the Andalusia Mosque and the Great Mosque of Meknes. These madrasas ran their own courses, sometimes becoming well-known institutions, although they tended to have much narrower curricula or specializations than the University centers.

Madrasas under the Ottoman Empire

Under the Ottoman Empire (1380-1918), the madrasas, or medrese (Turkish word) continued to be a central and common institution in society. Some changes took place within them, although these were mainly architectural. For example, madrasas were usually found in a külliye, an architectural ensemble built around a mosque that included a madrasa, kitchens, bakeries, and Turkish baths…[16]

Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566) established under his reign four types of general and two specialized madrasas, one devoted to the science of ḥadices and the other to medicine. The latter two held the highest rank in the hierarchy of the empire’s madrasas and maintained it until the end of the empire in 1918.[17] The Ottoman madrasas – especially from the modernization of the empire or tanzimat (1839-1876) – began to have a less flexible and more organized curricula, largely inspired by the model of Western universities. At the same time, they introduced other disciplines: languages such as English or French, poetry, natural sciences or political science…[18]

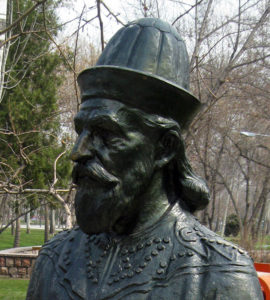

Madrasas were not limited to the great kingdoms or caliphates and continued to flourish and spread throughout the Silk Road to finally establish themselves in most Muslim countries.[19] In fact, many important madrasas developed in the peripheral areas of the Muslim world, such as Samarkand and Herāt (present-day Afghanistan), which were very famous cultural centres in the world of science, mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.[20]

Another madrasa stands out, still well known for its great beauty, the Ulugh Beg madrasa built in the 15th century in present-day Uzbekistan. This magnificent monument was located in the heart of the ancient city of Samarkand, better known as Registan Square.

Modernization and instrumentalization during colonization

However, the colonization of the European powers and the modernization of the Ottoman Empire radically changed the curriculum, the way of teaching and the organization of the madrasas. From that moment on, this informal institution was to be marked by greater control by the administrative authorities and by political power.

These social and political changes led to an evolution characterized by two opposing trends: one with a stricter focus on religious aspects, which developed around resistance to colonial power, and the other more Western, with a stronger focus on the “secular” sciences.[21]

In Algeria, under French domination, colonial madrasas were created with the aim of training civil servants and cadis. These madrasas were governed by the decree of September 30 of 1850, which placed them under military authority and managed by the martial administration.[22]

Each of them had at its disposal three Muslim teachers and one of them was in charge of the direction of the establishment. Beginning in 1883, a French teacher was also assigned to support the colonial policy of generalizing the use of French.[23]

Since the 10th century, madrasas have not ceased to change, depending on their political-social contexts and that they reached such importance that researchers such as George Makdisi have described them as models and references of the teaching of the Middle Ages.

The institution of the madrasa established by and during colonial rule then emerged as a more complex entity that absorbed both colonialist and traditionalist conceptions. Mirroring societies, madrasas in their diversity collaborated with colonial power, or, on the other hand, attempted to fight it through education. However, the most important thing we can highlight is that they were not a place of obscurantism or fanaticism, but an important place for the democratization of both religious and secular education.

It is from the 1980s-90s that the vision of madrasas changed radically, being more and more assimilated with extremism. The deconstruction of this discourse will be the subject of our second article, while this first one has allowed us to observe how – since the 10th century – madrasas have not ceased to change, depending on their political-social contexts and that they reached such importance that researchers such as George Makdisi have described them as models and references of the teaching of the Middle Ages.

[1] GRANDIN, Nicole y GABORIEAU, Marc « Madrasa : la transmission du savoir dans le monde musulman» Editions Arguments, 06/1997, p.1.

[2] Pedersen, J.; Makdisi, G.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R. (2012). «Madrasa». Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition.

[3] BLEUCHOT, Hervé. “Droit musulman : Tome 1 : Histoire. Tome 2 : Fondements, culte, droit public et mixte“ Aix-en-Provence : Presses universitaires d’Aix-Marseille, 2000

[4] Gabriel Malek. « Le rôle des medersas coloniales de l’Algérie française dans l’orientalisme du début du XIXème siècle », Lesclésdu Moyen-Orient.fr, 02/05/2018.

[5] Pedersen, J.; Makdisi, G.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R. (2012). «Madrasa». Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill.

[6] George Makdisi (1984) “The Rise of Colleges. Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 104, No. 3. pp. 586-588

[7] Griffel, Frank (2009). Al-Ghazālī’s Philosophical Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press

[8] Las cuatro escuelas suníes son: hanafí / malikí / shafi’i / hanbalí.

[9] Nikita Elisséeff, « MADRASA », Encyclopædia Universalis.

[10] BLEUCHOT, Hervé (2000). “Droit musulman : Tome 1 : Histoire. Tome 2 : Fondements, culte, droit public et mixte.“ Aix-en-Provence : Presses universitaires d’Aix-Marseil

[11] Matthew E. Falagas, Effie A. Zarkadoulia, George Samonis (2006). «Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 C.E.) and today», The FASEB Journal 20, p. 1581-1586.

[12] Ibid

[13] Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2007. Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and its Culture. The American University in Cairo Press.

[14] Gabriel Malek. « Le rôle des medersas coloniales de l’Algérie française dans l’orientalisme du début du XIXème siècle », Lesclésdu Moyen-Orient.fr, 02/05/2018.

[15] Ibn Khaldûn, « Le voyage d’Occident et d’Orient, Paris », Sindbad-Actes Sud, 1995. 336p.

[16] Kuban, Doğan (2010). Ottoman Architecture. Antique Collectors’ Club.

[17] Ibid

[18] Ibid

[19] Ibid

[20] David Vestenskov. “The Role of Madrasas: Assessing parental choice, financial pipelines and recent developments in religious education in Pakistan & Afghanistan”, Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen: 2018. 153p.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Gabriel Malek. « Le rôle des medersas coloniales de l’Algérie française dans l’orientalisme du début du XIXème siècle », Lesclésdu Moyen-Orient.fr, 02/05/2018.

[23] Ibid.

No Comments