These months of pandemic we are witnessing the controversy caused by the publishing of the so-called “surah Kuruna”, written in imitation of a Quranic sura. From the radical front, there has been a wave and threats through the social media, while in Europe, the event has been used to promote anti-Muslim racism and discrimination. An Islamic reading, however, shows a measured position, far from all extremism.

Daniel Gil-Benumeya – FUNCI

Translation: Alfonso Casani – FUNCI

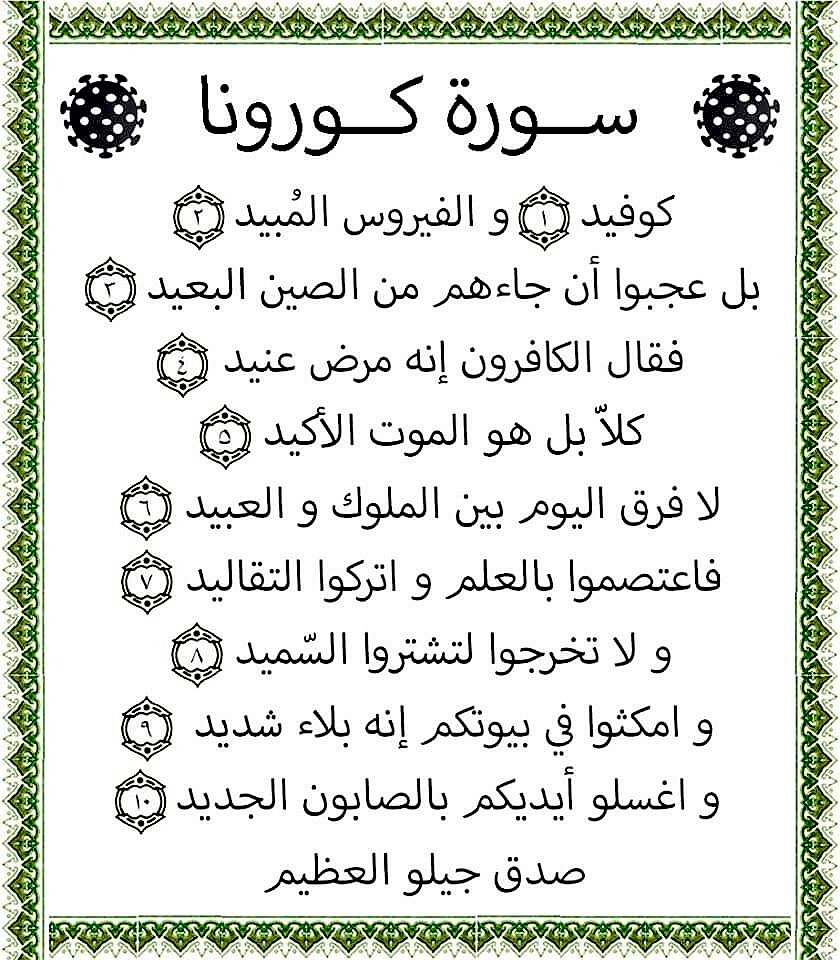

In March, coinciding with the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdown measures imposed all across the world, a young Tunisian woman wrote in her Facebook profile a humorous and apocryphal poem on the unparalleled situation we are living. The poem, written in classic Arabic, imitates the style of the Quranic verses in fact, it was titled surah Kuruna. Let us remember that the surah are each of 114 chapters in which the Quran is divided. The authorship of the poem (there are at least two versions of it in Arabic) remains unknown, so we don’t know the intentions behind the poem. For the use of the pararreligious language, we might think that he/she intended to raise awareness, ironically, about the need to take the pandemic seriously and the measures to combat it, while making fun of all fundamentalist reactions. The version shared by the Tunisian woman went along this lines:

Surat Kuruna

Covid

And the deadly virus

They are astonished to see it land from distant China!

The disbelievers say that it is a disease

But it is a certain death.

There is no distinction between kings and slaves.

Beware then, cling to science and abandon traditions

Don’t even go out to buy flour,

Stay at home, as it is an intense test,

And wash your hands again,

And trust in the exalted gel.

As it usually happens in social media, the publication generated a big controversy, which ended up in a judicial process against the woman for offense to religion. Blasphemy is not considered a crime in Tunisia, but, as it happens in Spain, religious offenses can be prosecuted by interpreting other laws extensively.

As it usually happens in these cases too, there was a reactive effect in defense of freedom of expression, and the diffusion of the poem increased exponentially. It went from being a more or less limited joke, to hit the headlines. It seems that a young French woman of Algerian origin received insults and death threats for duplicating the poem, while in Barcelona, other women recorded herself chanting it in the style of Quranic recitations, and was also subject to insults, harassment and threats. In addition, as it also happens in these cases, there are those who have linked these extremes with the inherent violence of Islam.

Science and preventive measures?

The poem itself does not have anything offensive towards Islam. Even the encouragement to trust more science and the preventive measures than the beliefs and traditions is in line with the Quranic exhortations to rely on good judgement and one’s own discretion instead on imitation, as well as the Islamic tradition of preventive medicine.

the Tunisian president himself publicly read, not long ago, a satirical poem that imitated the Quranic style and mocked the Western influence in the Arab constitutions.

In fact, most of the Islamic institutions all across the world have adopted preventive and social cooperation measures during this pandemic, closing mosques and restricting, for the first time, the public celebration of Ramadan. It is true that from the lines of Islam there have been some angry and ignorant reactions, just as in any other place (Spain is a good example of this, lately), but as in every other place, this seems to be an exception, not the rule (in spite of part of the media’s effort to make us belief the opposite). There should not be any contradiction between the false surah and the practice of Islam.

What might be perceived as offensive is the imitation of the holy book, not for the content but for the imitation of the style, and other provocative intentions assigned to the poem and its diffusion.

Classic poets

With regard to the first accusation, the imitation of the Quran is not something uncommon. One of the first classic poets in Arab literature, Abu al-Tayeb al-Mutanabbi (10th century), whose nickname means “he who beliefs himself a Prophet” owes the moniker to some verses he wrote in his youth defying the presumption of inimitability of the Quran. In spite of this transgression, he continues to be an icon for the Arab-Islamic culture, as it happens as well with Abu-l-Ala al-Ma’arri, Abu Nuwas, or Omar Jayyam, among others.

Thus, imitations and paraphrases of the Quran are not something rare, sometimes with the purpose of creating controversy, and sometimes used just as a rhetorical resource. We have to take into account that the Quran is also a literary work, and as thus, it has an impact on the Arab language and stylistics. For instance, as the Tunisian social media has reminded, the Tunisian president himself publicly read, not long ago, a satirical poem that imitated the Quranic style and mocked the Western influence in the Arab constitutions.

In defense of the Quran

In reality, if we consider that the Quran has a divine origin, as the Islamic belief does, it seems logic to conclude that it is in itself inimitable and inviolable, and therefore it does not need any defense or prophylaxis, as you cannot offend that which is the biggest (akbar) and that is beyond any other thing.

This seems to be suggested by the Quran itself, when it encourages the believers to react to blasphemy just by moving away and refraining to waste their time on discussions:

“And leave those who take their religion as amusement and diversion and whom the worldly life has deluded.” (6: 70)

“And it has already come down to you in the Book that when you hear the verses of Allah [recited], they are denied [by them] and ridiculed; so do not sit with them until they enter into another conversation.” (4: 140)

The Quran also forbid to offend the beliefs held by others:

“And do not insult those they invoke other than Allah, lest they insult Allah in enmity without knowledge. Thus We have made pleasing to every community their deeds. Then to their Lord is their return, and He will inform them about what they used to do.” (6: 108)

A sarcastic poem

The problem seems to be in the poem’s message, rather than in the imitation of the Quran, or actually, in what seem to understand by it. As in every communicative situation, the contexts, channel and reception might give different very connotations to every message. Social media is able to generate concurrent readings in very different context.

The Quran itself encourages the believers to react to blasphemy just by moving away and refraining to waste their time on discussions.

In Tunisia, where Islam is the majoritarian religion, as well as the emblem of some conservative political organizations, an irony on the Quran can be a means of transgression. Any belief or political idea can become a tool for social control. And there is no doubt that Islam can be used for that ideological purpose when institutionalized, in spite of the Quranic precepts: “There shall be no compulsion in the religion.” (2: 256), “The truth is from your Lord, so whoever wills – let him believe; and whoever wills – let him disbelieve.” (18: 29), among others.

It would be desirable that this wrong was solved at the discursive level, instead of turning religion into law and the transgression into crime, because faith is free. In any case, it is always good to remember that sense of humor can be one of the most power basis of spirituality.

Instrumentalization of Islamophobia

On the contrary, in the Europe or any other place where Isalmophobia is a means for the discrimination and social control of the Muslim population, any message that can be instrumentalized against Islam acquires a different nature and generates different reactions. For instance, these last months we have witnessed an unprecedented institutional, media and physical violence against Muslims in India, where they have been accused of spreading the Covid-19 virus, and almost of being the embodiment of the virus itself, with images and statements very close to those of antisemitism of the 30s.

In Europe, we have seen fake media campaigns against the Muslim communities as well, or against people of Moroccan origin or with any other feature linked to Islam, accusing them of breaking lockdown, opening mosques and enjoying some privileges that the rest of the population didn’t have. Likewise, in many countries (Spain among them) we have witness an increase in police violence and racial profiling. In this context, a controversy that links the holy book and the Covid-19 can become a way of nourishing an Islamophobic discourse, which already has a real impact on the Muslim population, in their social perceptions, and the repressive and security political measures being applied.

A controversy that links the holy book and the Covid-19 can become a way of nourishing an Islamophobic discourse.

Lastly, this controversy has a key importance in the communicative channel. Social media, in addition to contributing to the loss of communicative depth and details, unfortunately also allows for harassment and verbal violence. Bullying, pressure, threats, critics, revelation of personal data, offensive messages, identity theft, threats to one’s reputation, creation of fake profiles, etc. are some of the characteristics that define cyberbullying. Many of them have become common in social networks, especially when a message gains attention of delves into any controversial topic. The risk increases when the target is a woman, but it affects us all, even the President, in spite of having a protection that the rest of the citizens do not have.

For this reason, linking the threats made by certain individuals with regard to the “surah Kuruna” with “Islamic” terrorism, or with the condemning sentence issued by Khomeini against Salman Rushdie, seems more related to Islamophobia than to a real analysis of reality.

No Comments