This article, published by The Conversation, gathers some of the main findings of the study “Antisemitism and Islamophobia: measuring everyday sensitivity in the UK” (Jualian Hargreaves and Daniel Staetsky, 2019, Ethnic and Racial Studies Journal) on the perception of Jews and Muslims on Islamophobia and antisemitism in the UK. This interesting study deepens the role that factors such as age, birth place, or education, plays in the perception of discrimination and hate-speech in the country.

Accusations of antisemitism have been swirling around the Labour Party since Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader in 2015. He has been accused of harbouring antisemitic views and offering public support to party colleagues labelled as antisemitic. Meanwhile, the Conservative Party have faced accusations of “endemic” Islamophobia.

Accusations of antisemitism have been swirling around the Labour Party since Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader in 2015. He has been accused of harbouring antisemitic views and offering public support to party colleagues labelled as antisemitic. Meanwhile, the Conservative Party have faced accusations of “endemic” Islamophobia.

In the run-up to the 2019 general election, the main political parties have repeatedly accused each other of antisemitism and Islamophobia. Away from politics, there are widespread concerns about prejudice targeting Jews and Muslims. But the narratives are often simplistic and without supporting data. We hear much from politicians, community leaders and experts. We hear far less from “everyday” people and know relatively little about what Jewish and Muslim members of the public are likely to find offensive.

A recent study, published in Ethnic and Racial Studies, is the first known study to compare antisemitism and Islamophobia using statistics and found varying levels of sensitivity towards antisemitism and Islamophobia among British Jewish and Muslim communities. The study offers a rare insight into the sensitivities of “everyday” people within both communities.

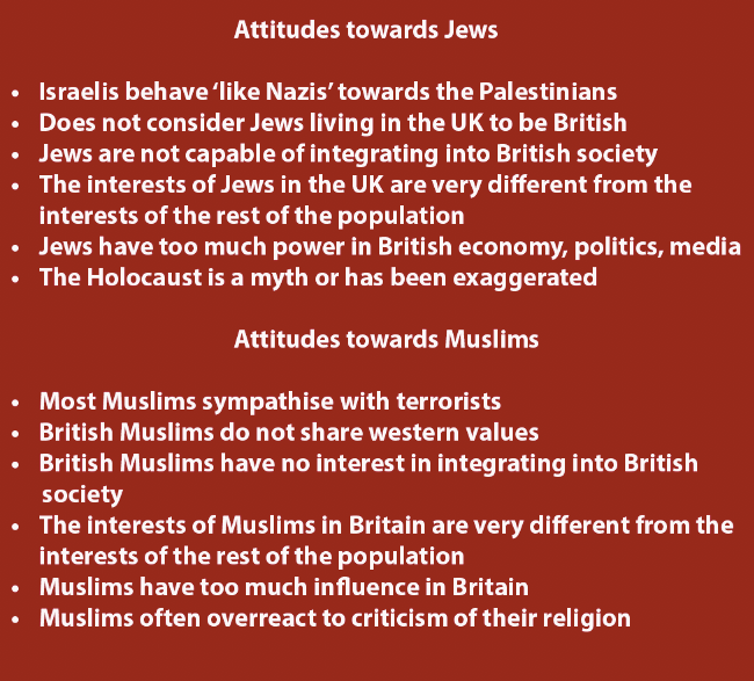

Statements designed to reflect antisemitic attitudes were shown to nearly 1,500 Jewish people, and 1,000 Muslim respondents were shown statements designed to be Islamophobic:

There was more certainty within the Jewish group about whether the statements were antisemitic or not. For each statement, only 1-3% of Jewish respondents answered “don’t know”. The Muslim group were less certain. For each Islamophobic statement shown to the Muslim respondents, between 15% and 22% answered “don’t know”.

Jewish respondents and Muslim respondents who knew how to “diagnose” the statements differed in their sensitivity towards them. The most offensive anti-Jewish statement was the statement about the Holocaust: 96% of Jews considered it antisemitic. Other statements were perceived as antisemitic by between 82% and 94% of Jews – large absolute majorities. Description of Israelis as being Nazi-like towards the Palestinians was seen as antisemitic by the smallest absolute majority of Jews, 73%. In stark contrast, none of the statements about attitudes towards Muslims were seen as Islamophobic by a majority of Muslim respondents.

Differences within each group

The study also found differences within each group. Jewish respondents aged over 40 were between 80% and 90% more likely to be sensitive than those aged between 18 and 39. Age was not a factor for Muslim respondents.

Education played an important role for both groups, but seemed to push sensitivity in opposite directions. Muslim respondents with degrees were 63% more likely to find all statements offensive. They were 70% more likely to be sensitive about Muslims not sharing western values. By contrast, Jewish respondents with degrees were 35% less likely than those without to be sensitive towards the linking of Israelis and Nazis. Jewish respondents in education were 66% less likely than those in employment to be sensitive to all the statements. They were 56% less likely to be sensitive to the linking of Israelis and Nazis.

Being born in the UK made a difference for both Jewish and Muslim groups. Jewish respondents born in the UK were 40% less likely to be sensitive towards the linking of Israelis and Nazis than those born in the rest of Europe. By contrast, UK-born Muslim respondents were around twice as likely as those born in Asia to be sensitive to all the statements

Explaining the findings

What does it all mean? How are we to explain the findings? The role of age in shaping sensitivity among the Jewish respondents could reflect the role of memory around the Holocaust and events such as the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the 1967 Six-Day War. Pivotal events shaping Islamophobia – the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, 9/11 and 7/7 – are more recent. When it comes to British Muslims and Islamophobia, perhaps the present matters more than the past.

Being born in the UK appeared to increase sensitivity for Muslim respondents but not for Jewish respondents. Perhaps present conditions in the UK are more likely to shape sensitivity towards Islamophobia than antisemitism.

Being born in the UK appeared to increase sensitivity for Muslim respondents but not for Jewish respondents. Perhaps present conditions in the UK are more likely to shape sensitivity towards Islamophobia than antisemitism (although the ongoing Labour Party row may be flattening out such differences).

The role of education suggests that understandings of Islamophobia are not equally distributed among British Muslims. This contrasts with antisemitism, with its longer history as a concept and demonstrably wider reach. Islamophobia is often debated at an elite-level in ways that are not always communicable to a wider audience. For example, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims’ use of “expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness” being targeted in its definition of Islamophobia seems highly likely to evade everyday understandings.

Whatever the true explanation, simplified descriptions of the impacts of antisemitism and Islamophobia on Jewish or Muslim communities simply won’t do. The study shows that assuming all Jews and all Muslims react to antisemitism and Islamophobia in the same way is likely to be inaccurate.

Source: The Conversation

No Comments