Dídac P. Lagarriga

*(Translation of an article originally published in Diari ARA, Barcelona, 16-05-2019)

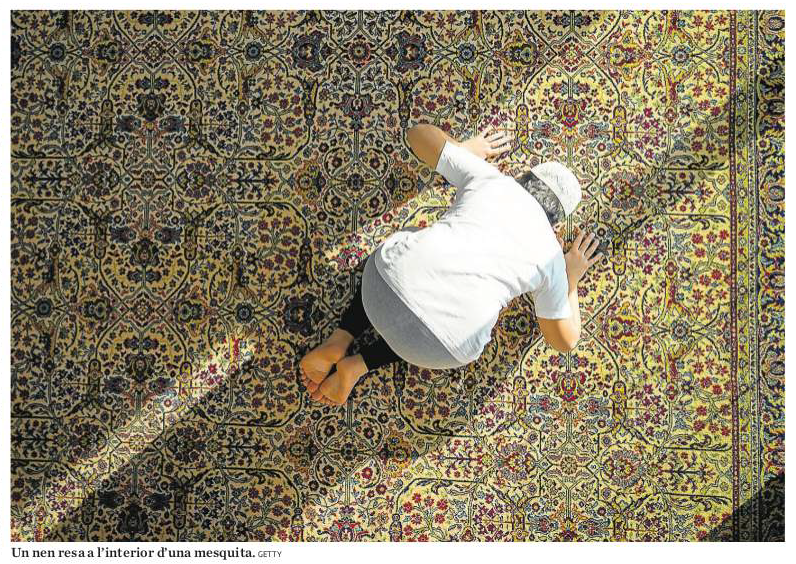

Good and bad. Without shades, ignoring all complexities, ignoring that to live is to assume we are diversity, both socially and individually. And yet, we tend to look for good and bad, homogeneous and immutable. We know that Islam, since 9-11, is in the spotlight. An Islam that resists to be understood as a homogeneous block, and that, because of that, keeps receiving all kind of labels in an attempt to understand it. From outside and inside, that is, many Muslims also participate in this current trend of labelling each other, defining themselves and differentiating each other.

In the last years, and as a consequence of the complex sociopolitical context, the idea of a moderate Islam opposed to a radical Islam is growing stronger. The good and the bad, as always, are fictional characters that allows us to create our own fantasies. But the category of “good” and “bad” –or in the politically correct terms, “moderate” and “radical”– are contextual and temporary, not an essence that impregnates Muslims from the cradle to the grave. There is, however, the desire of essentialising the other, and even essentialising oneself. To essentialise as an escape from time, context, experience, unexpected changes or vital processes. Only by essentializing the others and oneself –that is, by a desire of being immutable– can one dream with living history, and, who knows, maybe being immortal.

Fluent categories

“There is a fluency and flexibility in the variety of historical, social and political situations in which they are found.”

Leaving fantasies aside, labels cannot freeze. A moderate Islam against a radical Islam as the only two possible and confronted Islams? This might facilitate the analysis and the creation of discourses –one of the reasons why labels are actually so successful–, but we will continue to give credit and to antagonize two highly questionable categories. The number of voices questioning this instrumentalization is increasingly growing. Unfortunately, they are not that many yet and they come from the scholar world. Moreover, when they reach the media field they tend to fizzle out, dissolved in the requirements of the media to expose facts in a brief and schematic way. This voices are also silenced by the instrumentalization of power and the political and identitary strategies of those sectors interested in maintaining this imaginary of moderated versus radicals.

As explained by the anthropologist Jean-Loup Amselle, specialized in West Africa, “there is a fluency and flexibility in the variety of historical, social and political situations in which they are found. The religious actors erase the trails, cross frontiers and mix without complexity the allegedly paradoxical entities. The categories of Sufi, Salafi, fundamentalist, Wahhabi, reformist, radicalized Muslim or others only have the use we want to give them, and they only work as markers in the frame of junctures with political order consequences.”

Fabienne Samson, anthropologist specialized in Islam in Senegal, insists in this same approach: “We are facing a terminology that doesn’t reflect reality anymore. In order to follow the evolution of religious mutations, today some researchers speak of neo-brotherhoods, neo-Sufism, liberal Islam, cultural Islam… Post-Islamism, post-reislamization or neo-fundamentalism are other new formulas that try to portray the new Islamic dynamism across the world. But this plasticity –Samson concludes– doesn’t really fit with the complexity of the recomposing of contemporary Islam.”

Risk of exclusion

Islam, in singular, already comprises all that range of pluralities, of forms that fold and unfold within the self and the community. To take one, any of them, and make an idol of it would possibly nullify Islam.

Clear plasticity, inseparable of the same act of living. We are inhabited by several categories and, at the same time, we inhabit categories that fit with the way we are trying to live. Islam, in singular, already comprises all that range of pluralities, of forms that fold and unfold within the self and the community. To take one, any of them, and make an idol of it would possibly nullify Islam. For this reason, as it usually happens nowadays, there are many voices looking cautiously at the emphasis given to the so-called moderate Islam, mainly represented in its more spiritual branch: Sufism. It is true that the term itself is already plural, and when we talk about “Sufism” we can be referring to many things, but they are linked by spiritual education, asceticism, and its emphasis on an inner path. The risk is to think that a Muslim who doesn’t define himself as Sufi is automatically excluded from this will for inner purification. As if Islam on its own wouldn’t have this spiritual dimension and we need to add a supplement. The shaping of the label itself needed three centuries to develop in the Islamic history, which doesn’t mean that, during that time, there weren’t ascetics, mystics, or people involved in the inner self. The French philosopher Abdennour Bidar, who was part of a Sufi brotherhood for several years, is very critic with their tendency to sectarianism and exclusivism: “Sufism profits from an image of a peaceful and open spirituality that generates many illusions. It is time to break the myth of a Sufism that would be “the other Islam”. Beware of mirages!”

Likewise, professor Mahmood Madani, author of Good Muslim, Bad Muslim warned of playing along to the fictitious division of two Islams, which automatically turns a big part of Muslims in potential terrorism for the fact of not fitting into the category of “good”. And adds, “When I read about Islam on the newspapers, I feel I am reading about “museumized” peoples. Their culture seems not to have a history, nor politics, nor debates. It seems that they have been petrified in a habit with no life. Moreover, this people seem to be unable to change, and their only salvation is, as usual, to be saved from the exterior”.

Likewise, professor Mahmood Madani, author of Good Muslim, Bad Muslim warned of playing along to the fictitious division of two Islams, which automatically turns a big part of Muslims in potential terrorism for the fact of not fitting into the category of “good”. And adds, “When I read about Islam on the newspapers, I feel I am reading about “museumized” peoples. Their culture seems not to have a history, nor politics, nor debates. It seems that they have been petrified in a habit with no life. Moreover, this people seem to be unable to change, and their only salvation is, as usual, to be saved from the exterior”.

No Comments