Middle East teacher and expert, Nader Hashemi, collaborator the Islamic Culture Foundation in his protect “Islam and constitutionalism: an open dialogue”, has just published, along with researcher Danny Postel, the book: “Sectarization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East”. This book analyzes the process and state of sectarization in the Middle East, with the aim of explaining how this phenomenon has become one of the most common arguments to justify the region’s conflicts. As a result, economic and political problems have been largely overlooked. The following review, published by Middle East Reviews, gathers the main topics treated in this work.

Much of the contemporary analyses on the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, namely Syria and Iraq, take it for granted that the violence is rooted in a 1,400 year-old conflict between Sunni and Shia Muslims. This neo-oriental assumption centers religion as the main category of analysis and frames it as the primary cause and site of conflict in the region. Much like Northern Ireland and the former Yugoslavia, sectarianism is presented as a product of atavistic hatreds, which are endemic to local communities and trans-historical in nature. This approach implies that sectarianism persists despite socio-economic and political change. Hence, works like Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East are an important and timely response to the dangerous sectarian meta-narrative that pervades much of contemporary thinking on the topic.

Much of the contemporary analyses on the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, namely Syria and Iraq, take it for granted that the violence is rooted in a 1,400 year-old conflict between Sunni and Shia Muslims. This neo-oriental assumption centers religion as the main category of analysis and frames it as the primary cause and site of conflict in the region. Much like Northern Ireland and the former Yugoslavia, sectarianism is presented as a product of atavistic hatreds, which are endemic to local communities and trans-historical in nature. This approach implies that sectarianism persists despite socio-economic and political change. Hence, works like Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East are an important and timely response to the dangerous sectarian meta-narrative that pervades much of contemporary thinking on the topic.

Edited by Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel, this volume brings together scholars from different academic disciplines to address the term sectarianism as it pertains to the Middle East. Rather than framing sectarianism as a religious problem, the authors see it as something, which is strategically and cynically deployed by different political actors, including states, to promote and advance their own parochial agendas. Hence, one of the central arguments of this book is that elites have manipulated sectarian identities as a tool to hold on to power, seemingly at any cost and to the detriment of the region.

Works like Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East are an important and timely response to the dangerous sectarian meta-narrative that pervades much of contemporary thinking on the topic.

Given the history of use and abuse of the term sectarianism, not to mention its conceptual fuzziness as an analytical category, a new term called “sectarianization” is advanced. This rightly recognizes that the mobilization around a sectarian identity is political and social. It is a contingent process and not, as mentioned earlier, a trans-historical phenomenon embedded in the social landscape. Following the introduction, the book is divided in two sections. Part one of the text discusses sectarianization in its historical, geopolitical, and theoretical perspectives, while part two guides the reader through various rich case studies, illustrating the processual nature of sectarianization. The rest of the review will selectively highlight the main strengths of this work.

Historical Roots of Sectarianization

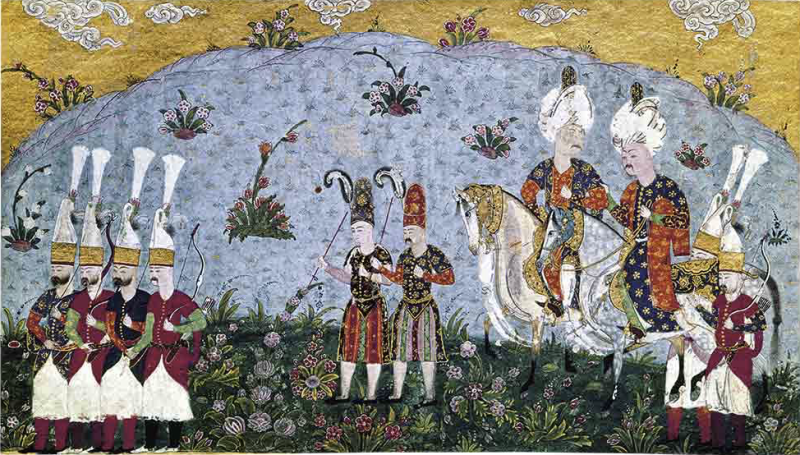

In the first chapter of the book, Ussama Makdisi argues that the sectarianization of the Middle East began with the unraveling of the old Ottoman socio-political order, grounded in privilege and hierarchy on one hand and the recognition of difference on the other hand. However, the challenges and pressures posed by the various European powers led to a project of radical reform known as the Tanzimat. This series of reforms introduced new political concepts such as equality before the law regardless of religion, nationalism, and citizenship. This would dramatically alter the socio-political landscape of the Ottoman Empire, where the ideological and material relationship between the ruler and ruled was transformed. These events inadvertently lead to a dramatic rise rapid rise in inter-communal violence between different religious and ethnic communities. In response to the violence, the Ottoman authorities along with the European powers created and institutionalized sectarian political systems such as the Mutasarrifiyya of Mount Lebanon. Although a product of colonial politics interacting with local conditions and actors, sectarian systems of governance would be back-projected into the distant past and hence became a part of the “natural” political order of the Middle East.

Contemporary Sectarianization

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the formation of nation-states, the process of sectarianization in the region continued apace although with different trajectories and particularities depending on the state. For instance, Bassel Salloukh’s chapter on the architecture of sectarianism in Lebanon neatly lays out the pernicious infrastructure in its material practices and legal, discursive, and ideational dimensions, which underpins and reproduces sectarianism in Lebanon. In the absence of viable political alternatives sectarianism has achieved a sort of ideological primacy in the country. Moreover, as Yezid Sayigh illustrates in his chapter any cogent analysis of sectarianization must also focus on the internal dynamics of (Arab) states and not center solely on colonial and imperial policies in the production of sectarianism. Besides affirming the agency of local actors, the analysis rightfully implicates them as well.

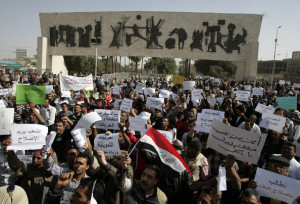

A major turning point in the sectarian relations in the Middle East came with the American invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003.

A major turning point in the sectarian relations in the Middle East came with the American invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003. On a local scale this event created the conditions for the sectarianization of Iraqi society and politics. On a regional scale, the Saudi-Iranian rivalry dramatically  increased with both sides playing the sectarian card, albeit in different ways. Analyzing the case of Iraq, Fanar Haddad in his chapter argues that the roots of Iraq’s current sectarian moment can be found in its recent authoritarian past. Of course, this phenomenon only achieved full expression with the institutionalization of a sectarian political system implemented by the American occupation authorities. Thus, the move unleashed different sectarian entrepreneurs on the Iraqi political and electoral scene with predictably disastrous results. Interestingly, Haddad writes that with the ongoing violence in Iraq, a politicized if uncertain Sunni identity has emerged in the field as a reaction to the sectarianization of Iraqi politics, which was not present there before.

increased with both sides playing the sectarian card, albeit in different ways. Analyzing the case of Iraq, Fanar Haddad in his chapter argues that the roots of Iraq’s current sectarian moment can be found in its recent authoritarian past. Of course, this phenomenon only achieved full expression with the institutionalization of a sectarian political system implemented by the American occupation authorities. Thus, the move unleashed different sectarian entrepreneurs on the Iraqi political and electoral scene with predictably disastrous results. Interestingly, Haddad writes that with the ongoing violence in Iraq, a politicized if uncertain Sunni identity has emerged in the field as a reaction to the sectarianization of Iraqi politics, which was not present there before.

Another major turning came in 2011, with the Arab Spring, when the people demanded their rights and the end of authoritarian regimes. For a brief moment, it seemed that it would succeed but the Gulf monarchies held the line and ferociously fought back. Leading the way was Saudi Arabia, which as Madawi al-Rasheed in her chapter contends, invoked the specter of sectarian difference in order to divide and weaken the opposition in the country. She argues that the real threat to the Saudi regime is not the dissident Shi’a notables of the eastern province, but a united cross-sectarian political opposition that can credibly challenge it. Ultimately, she writes, the Saudi royal family’s calculations are not motivated by an innate sectarian solidarity, but the desire to hold on to power, even if it means polarizing Saudi society. In his chapter on Syria, Paulo Gabriel Hilu Pinto argues that the process of sectarianization proceeded from different vectors but it was the Syrian regime’s framing of the initial uprising for freedom and dignity as a Sunni Salafi uprising and positioning itself as the defender of religious minorities that greatly contributed to the current civil war. This discursive move, backed by the selective distribution of physical violence according to the sect, gave an opportunity to Islamist and jihadi actors to claim that they are the defenders of Sunni lives and interests. Moreover, their actions have been buttressed by the financial largesse of the Gulf monarchies, which have also been promoting sectarianism in the region. Sectarian violence has become a self-fulfilling prophecy and as the civil war grinds on, sectarianization serves as a tool of mobilization and indoctrination.

Like in the former Yugoslavia, the deployment of sectarian language, rhetoric, and practices by different actors (supported by outside powers) has had the effect of masking deep social, economic, and political cleavages in a given society. It was and remains a route to power and wealth as the case of Bosnia illustrates. What this empirically rich and theoretically sophisticated volume shows is that there are multiple processes that drive sectarianization in the Middle East, and not religious fanaticism. It decisively rejects simplistic and orientalist depictions of Middle Eastern societies and history. I would highly recommended this book for both undergraduate and graduate courses in contemporary Middle Eastern politics.

Authors: Nader Hashemi y Danny Postel (eds)

Publisher: Hurst & Company

Date: 2017

Pages: 384 págs.

Place of publication: Londres

No Comments