Controversy ensued immediately after Disney announced that it would remake Aladdin, the cartoon fantasy film released in 1992. The outcry centred largely on the casting for the film, and specifically, who would play the roles of Aladdin and Jasmine.

For Disney, Aladdin is far more than just a film. It is a multimillion-dollar franchise – one that encompasses television and film spin-offs, rollercoaster rides, Halloween costumes, and scores of trademarked toys, gadgets and other products that generate considerable revenue for the mass media and entertainment conglomerate. The live action remake, to be directed by British director Guy Ritchie and slated for release in theatres in 2018, will be the latest instalment of Disney’s Aladdin franchise.

For the diverse groups of people that hail from the Middle East, the region that inspires the story and setting for Aladdin, the film renews a range of concerns. Aladdin, the film and its aggregate franchise, is not only a material embodiment of Orientalism – the system that reduces the Middle East, and its elaborately diverse peoples, cultures and faiths, into a backwards monolith – but also an enterprise that generates extravagant profits from perpetuating these misrepresentations.

The film disseminates dangerous representations of the Middle East, and its peoples, to the youngest and most impressionable minds

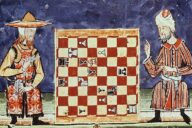

Beyond problematic characters and themes, Aladdin’s Agrabah, the fictitious Middle Eastern setting of the film, is a cartoon remake of the Orient, a fictive and distorted recreation of the Middle East itself. A made-up place based on a made-up place.

Therefore, while who plays Aladdin and which actress assumes the role of Jasmine deserves attention, the bulk of the concern and criticism should be concentrated on the story’s inherent Orientalism and racism. The film disseminates dangerous representations of the Middle East, and its peoples, to the youngest and most impressionable minds, at a time of intensifying Islamophobia in the United States,Europe, and beyond.

The Orient is not Arab

Rumours of the forthcoming Aladdin film struggling to find actors for its lead roles setsocial media ablaze. The film’s casting became a globally trending topic, with allegations of racism and colourism and, more specifically, whitewashing – Disney seeking to cast white actors for the roles of Aladdin and Jasmine – driving the apparent controversy. Earlier this month, Disney responded to the media storm by casting Egyptian Canadian Mena Massoud to play Aladdin and Naomi Scott as Jasmine.

Casting Massoud seemed to appease those seeking racial concordance with the actor and character, while the decision to hire Scott, who is half Indian (and half white), still left many dissatisfied.

Certainly, casting an actress of Indian descent to play an Arab, or an Agrabian, continues the Orientalist tradition of conflating Arab and Indian, Middle Eastern and anybody and everyone Brown. But, upon closer inspection, are Jasmine, Aladdin, and the rest of the characters in the film Arab at all? Aladdin is supposed to take place in the Arab World or the Middle East or the Muslim World, which to the broader public and scores of Hollywood filmmakers, are interchangeable. But it doesn’t. The story is set in Agrabah, which is what Orientalism imagines Arab or Middle Eastern authenticity to be.

Would a non-Orientalist Aladdin be a success in a country where 41 percent of the electorate who voted for the current president and would vote in favour of bombing the fictional land of Agrabah?

Therefore, to some measure, the demand to cast Arab actors to play the lead roles in Aladdin amounts to an endorsement that Agrabah is indeed an Arab land or an accurate representation of the Arab world. And accepting that sanctions a host of vile stereotypes that attach to and emanate from an imagined “barbaric” region where “they will cut off your ear if they don’t like your face”. Agrabah is not the Arab or Muslim world, but a spitting cartoon image of the Orient – a centuries’ old production of academics and artists, news media and filmmakers, which casts it and its inhabitants as the mirror opposite of everything modern, liberal, and Western. Agrabah is the Orient, plain and simple, in cartoon form.

The cinematic recreation of Orientalism that lays the foundation of Aladdin – not merely the actors cast to play its caricatures – should drive criticism of the forthcoming remake. Although the remake will cast an Egyptian as Aladdin and a brown actress as Jasmine, concern and criticism of it should not be muted or mooted. Brown actors playing brown characters only scratches the surface of Hollywood’s inherent racism problem.

Aladdin will always be problematic

The content of films dealing with Arabs and Muslims, the Middle East and the Muslim world are far more important than the racial identity of the individuals slated to play key roles.

After all, scores of Arab, South Asian, and Muslim actors have lined up to play the roles of terrorists in Hollywood and television productions, among other damaging caricatures. If the film’s ideas, images, and central themes disseminate Orientalist messages, then the fact that a terrorist is played by an Arab actor or Aladdin performed by an Egyptian actor is, ultimately, unimportant.

Jafar, the primary villain, is always menacing and bent on inflicting harm, embodying the stereotype of the brooding and angry Arab villain.

All that said, to what extent can Aladdin be purged of the Orientalist and bigoted foundation of the original screenplay? Can a franchise so conflated with Orientalism do so at all without entirely losing its very essence?

Violence, a trope closely linked to Arabs and Muslims, is ubiquitous in Aladdin. Jafar, the primary villain, is always menacing and bent on inflicting harm, embodying the stereotype of the brooding and angry Arab villain. This trope extends beyond Jafar to the very essence of Agrabah’s primitive and patriarchal culture in which masculinity is defined by violence. The scarce representations of women is marked by the typical Orientalist understanding of the Arab female: silent and submissive – like the women servants of the palace – but also exotic and salacious, like Jasmine.

How much would Guy Ritchie change these problematic representations, if his audience actually enjoys and believes them? Would a non-Orientalist Aladdin be a success in a country where 41 percent of the electorate who voted for the current president and would vote in favour of bombing the fictional land of Agrabah?

How much would Guy Ritchie change these problematic representations, if his audience actually enjoys and believes them? Would a non-Orientalist Aladdin be a success in a country where 41 percent of the electorate who voted for the current president and would vote in favour of bombing the fictional land of Agrabah?

The remake of Aladdin will have to answer all these questions at a time of high sociopolitical stakes, when the clash of civilisations and its Orientalist foundation are far from a cartoon fantasy, but formal state policy.

Source: Aljazeera

No Comments