The ‘heart of Europe’ – as the Czech Republic is often called – is slowly but surely becoming a centre of intolerance towards certain nationalities, ethnic groups, and religions. Under the cover of ‘freedom of speech’, politicians, media, and various hate groups are actively spreading hatred and fear, particularly targeting religious and cultural minorities. In a country which is significantly less touched by emigration from the Mediterranean than for example Italy, Spain or France, an increasingly racist and xenophobic rhetoric is nevertheless emerging.

And I cannot help but wonder, what and when went wrong? And most importantly, can we stop it?

Czech but still a foreigner

I was born in the Czech Republic to a Czech mother and an Iraqi father. Growing up, I was raised without any major focus on my half-Arabic origin, as my father doesn’t even practice Islam. I could say that my childhood was ‘typically Czech’. However, ever since primary school, I could feel that people around me perceived me somewhat differently than my peers. My skin was darker than the others, and my eyes and hair were very dark brown — characteristics that are not so common for Czech children. Sometimes I would hear some mean comments towards me, however, none of them made much sense, as I didn’t think of myself as being any different than the others.

Most of Czech (and in fact a lot of European) society sees Arab people through a lens of prejudices fuelled by fear and hatred.

It wasn’t until grammar school, when I started to hear insults about the origin of my father, that I understood how being an Arab affects the way people treat you. I quickly learned how most of Czech (and in fact a lot of European) society sees Arab people through a lens of prejudices fuelled by fear and hatred. Prejudices which formed during the nineteenth century and were particularly enhanced during the twenty-first century. For example, in 2001, the 9/11 attacks – and the subsequent U.S.‑led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq – triggered a worldwide wave of suspicion and hatred toward Arabs and Islam, entrenching harmful stereotypes about them on a global scale 1. Still, I never understood why this could affect me. And more importantly, what were the causes of the Czech situation?

Prejudice without presence

When speaking about the Muslim or Arabic community within the Czech Republic, it is noteworthy to look into some statistics. The Czech Republic, a landlocked European country, has a population of almost 11 million people. From that, 92.3% is Czech, 0.9% Slovak, 0.7% Ukrainian, and 6% of people have either a different nationality than those mentioned, or have two nationalities 2. As for religion, 11.7% are Christians, 1.2% are of different belief, 30.1% are unanswered, and almost 57% are without any religion 3. The estimated number of Muslims in the Czech Republic, as researched by the Pew Research Center in 2016, is 22,000 people, which is a mere 0.2% of the population of the Czech Republic 4. In 2021, the official number of people registered for Islamic belief was of only 5,132 (0.05% of the whole population) 5.

From these statistics, it is obvious that the Muslim community forms a very small part of Czech society, practically unnoticeable if we compare it with, for example, the 10% population which identify as Muslims in France 6. And even if we were to include to these numbers the people of Arabic origin who do not practice Islam and thus are not registered in this percentage, the majority of the Czech population would still be entirely Czech, or of another Slavic nationality. It is also noteworthy that in the Czech Republic, there are no significant records of violence or organised crime attributed to the Muslim or Arab communities.

So, where does the prejudice against Muslim or Arab people in the Czech society come from, when, considering the data, this is a prejudice against a population almost absent from the country? And what motivated, and still motivates, Czech people to behave differently — fearfully and with prejudices — when being confronted with persons of Arabic origin or topics related to Islam and Islamic culture?

Vandalised wall of a mosque in Brno saying: ‘Don’t spread Islam in the Czech Republic! Otherwise, we will kill you’, 2020. © IslamOnline.sk

How Islam is being politicised

To understand the causes of Islamophobia (dislike of or prejudice against Islam or Muslims) in the Czech Republic, we must consider from which sources the general public gains information — mainly from TV, online news, radio, print, and social media. These platforms strongly influence public perception. However, to what extent can we rely on them to convey unbiased information?

Czech media often portray Islam, Muslims, and Arabs in a way that is both negative and stereotypical. Terms like ‘Islam’, ‘jihad’, and ‘extremism’ are frequently used without explanation, leading to confusion. Coverage focuses on terrorism, women’s oppression, and foreign cultural conflict, reinforcing an ‘us vs. them’ mentality, thus worsening the othering of the Arab population within the country. Furthermore, the media rely on provoked emotions, such as fear and anger, and secondary sources, which undermines the depth and accuracy of reporting. Not to mention that far-right and anti-Islam voices are often given more space, while ordinary Muslim perspectives remain largely invisible. As a result, the media contribute to fear, prejudice, and a distorted image of a small but largely peaceful minority.

Czech media often portray Islam, Muslims, and Arabs in a way that is both negative and stereotypical. Terms like ‘Islam’, ‘jihad’, and ‘extremism’ are frequently used without explanation, leading to confusion.

Politicians, often owning or influencing the Czech media themselves, contribute even more to the politicisation of Islam. Many use anti-Islam rhetoric to provoke fear and win support by presenting themselves as protectors against an alleged ‘Islamic threat’.

The far-right Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) party, led by Tomio Okamura, is particularly vocal. They publicly describe Islam as incompatible with democracy and on the party’s website even propose banning mosques, hijabs, and public prayer 7. Similar views appear across other parties: in 2008, the National Party, and later Okamura’s Dawn party, used racist posters — a white sheep kicking a black sheep out of the Czech flag— to call for the rejection of immigrants and the preservation of Czech national identity. This motive was previously used by the right-wing populist Swiss People’s Party, the German neo-Nazi party Die Heimat (NPD), and the likewise far-right Italian League of the North (Lega Nord) 8.

The Dawn party also wrote next to the poster on their Facebook page the following statement:

‘WE DON’T WANT ANY UNADAPTABLE IMMIGRANTS, UNADAPTABLE MINORITIES, OR RELIGIOUS FANATICS IN OUR COUNTRY. We are the only party in the Czech Republic that advocates this and says it straight out… We want to preserve the Czech, Moravian, and Silesian character of our republic, which our ancestors built over centuries. NO TO IMMIGRANTS AND UNADAPTABLES’ 9.

Posters of the extremist and neo-Nazi European parties: German Die Heimat, Swiss People’s Party, Czech National Party, and Czech Dawn party. © romea.cz

But it is not only the political parties that spread Islamophobic messages. Former prime minister Andrej Babiš once said, “They won’t be telling us who should live here.”, in response to migration policies as suggested by the EU in 2017 10. Similarly, former president Miloš Zeman declared that integrating Muslims into Czech society is “practically impossible” 11.

Demonstration against Islam in Brno led by the anti-Islamic group ‘We don’t want Islam in CR’, 2015. © Anna Vavríková.

This widely and publicly proclaimed anti-Islamic sentiment has, unfortunately, encouraged the formation of radical hate groups in the Czech Republic. Martin Konvička, a Czech entomologist and associate professor, in 2009 founded the group ‘We Don’t Want Islam in CR’, and later on a movement from this group derived – ‘Block Against Islam’.

Their most infamous act took place in 2016, when they staged a fake invasion of Prague by Islamic State at the Old Town Square. Dressed as jihadists with fake weapons and riding in a military vehicle with a camel and a goat, the group shouted ‘Allahu Akbar’ (‘God is the greatest’) and enacted a mock beheading 12. Many people who were present, including many tourists, recall the chaos and confusion they felt, not being sure whether it was a real invasion or not, some started to run, and some even to lay down on the ground in fear 13. This was not only an expression of Islamophobia, but also a deliberate act of psychological terror disguised as protest.

Invasion of Prague by the Islamic State as staged by the hate group ‘We don’t want Islam in CR’, 2016. © Petr Zewlakk Vrabec

The group continued with provocative actions: mocking the Hajj pilgrimage in front of the Saudi embassy 14, gathering at mosques to eat pork and drink alcohol 15, and displaying mannequins of stoned women across Prague 16. In 2015, Konvička openly stated:

“Our long-term goal is to place Islam on the same level as Nazism, to ban its dissemination, promotion, and public practice, to harshly suppress its public manifestations, and at the same time to condemn it socially.” 17.

Stoned mannequin of a woman as part of an anti-Islamic act in Prague, 2015. © Initiative ‘We don’t want Islam in CR’.

Is there any way out?

Islamophobia cannot be just passively observed—it must be actively countered. The normalisation of anti-Islamic sentiment in the Czech Republic demands a clear and active response. It is crucial to cultivate spaces that counter hate and fear with knowledge, empathy, and dialogue.

Cultural institutions, and museums in particular, hold a unique power to shape public perception. Museums, as institutions with an educational function and a history of public trust, can challenge the misleading narratives, and foster understanding between diverse groups. The Asian Cultures collection at the National Museum in Prague presents a unique opportunity to gain insight into the historical and cultural significance of these objects. Held by the Náprstek Museum, the collection comprises roughly 53,000 items covering regions such as the Middle East, Central Asia, India, East and Southeast Asia. The objects of Islamic origin are predominantly from Iran and Middle East, with most of them dating back to the middle of the nineteenth century. Similarly, the National Gallery in Prague holds over 13,000 objects of Asian origin, under the Asian Culture collection. The amount of Islamic objects within this collection is liminal, however not non-existent. The National Gallery is planning an exhibition to be opened in October this year, after its postponed opening in April, where the objects of the Asian collection should be displayed. Under the name ‘The Art of Asia Across Space and Time’, the Gallery will present a selection of 520 artworks from Asia and the Islamic world 18.

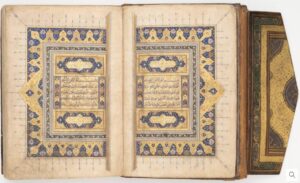

Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Tabrizi (calligraphy), Manuscript of the Qur’an, Iran, 1462 CE. © National Gallery Prague.

In its introductory newsletter, we can read that the exhibition should focus not only on the presentation of objects, but also the historical context of European Orientalism and colonial politics that influenced the views on the Asian and Islamic artistic traditions in the Czech lands 19. It is obvious, that this exhibition is aiming to foster intercultural connections and critical revisiting of historical approaches. However, its focus on the ‘Arts of Asia’ might be, in my view, too broad and risk prioritising some objects and narratives over others. While it represents an important step towards inclusive narratives within the Czech cultural sphere, I believe there should be efforts to curate an exhibition dedicated solely to Islamic objects, which could serve as a meaningful response to the growing Islamophobia.

Similar action is, however, not to be expected soon from the National Museum, namely then the Náprstek Museum (which belongs to the National Museum). Their collection of Asian art, and especially then the Islamic artworks, is more numerous than the collection of National Gallery (however, an exact number is not stated). In the sub-collection ‘Metal artworks from the Middle East and India’, we can find remarkable works from Iran dating back to the nineteenth century 20. Objects such as platters, bowls, caskets, and many more, show a curious decoration of not only floral motives—typical in Islamic art—but also motives figurative. This fact itself appeals us to speak about the historical narrative of such objects, that were allowed to carry a figurative motive, while produced and owned by an Islamic dynasty. If we were to create an exhibition showcasing this part of history, we could help to foster a nuanced understanding, how inclusive and open‑minded the Islamic belief, and artworks created under it, was and still can be. Through careful presentation and contextualisation, such objects have the potential to challenge reductive views of Islam as inherently iconoclastic or culturally rigid. In doing so, they can act as powerful tools against Islamophobic narratives, offering concrete, tangible evidence of the pluralism and aesthetic richness that have long defined many Islamic traditions.

Left: A casket with floral and figurative motives, 19th century, Iran; Right: A platter with floral and figurative motives, 19th century, Iran. © National Museum Prague.

In doing so, the museum could serve as a platform for inclusive discourse by creating spaces where individuals from diverse backgrounds, beliefs, and experiences can feel acknowledged, valued, and heard. This can be achieved by presenting artefacts and their histories in a manner that is inclusive and respectful of all perspectives. By embracing its role as a mediator, the museum can help society move towards a more inclusive and diverse future. It is a way for constructing a narrative and telling stories about Islamic beliefs that are not distorted by politics or the media.

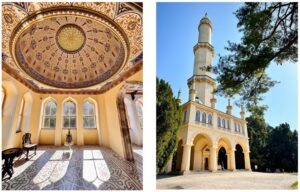

Even historical monuments located in Czech lands, like the elaborate Minaret in Lednice, built at the very beginning of the nineteenth century as a Romantic garden folly for the prince Alois I of Liechtenstein, invite reinterpretation. Often dismissed as a curious architectural oddity, it can today be recontextualised as part of a broader European history of Orientalism and used as a site to examine the cultural fantasies, anxieties, and projections that have long shaped how Islam has been perceived. Its very presence in the Czech landscape is a reminder that Islamic culture, whether in reality or imagination, has never been entirely ‘outside’ of Europe.

In the end, the ‘heart of Europe’ cannot remain healthy if it beats only for some. A society that defines itself by exclusion becomes weaker, more brittle, and more afraid. But a society that chooses empathy and understanding can still shape a different future, one in which being Czech does not mean being closed.

Interior and exterior of the Minaret located in Lednice, the Czech Republic. © Taťána Kynčlová, Novinky.cz.

Daria Ghaloomová

Front cover: Demonstrators march during an anti-immigrant rally in Prague on September 12, 2015. © David W Cerny, Reuters.

References

1 Evelyn Alsultany, “Arabs and Muslims in the Media after 9/11: Representational Strategies for a ‘Postrace’ Era”, American Quarterly, 65/1 (2013), pp. 161-169.

2 Wikipedia contributors. (2025, August 3). Czech Republic. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Czech_Republic

3 Ibidem

4 Pew Research Center. (2017, November 29). Europe’s growing Muslim population. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/11/29/europes-growing-muslim-population/

5 Náboženská víra. (2021). Sčítání 2021. https://scitani.gov.cz/nabozenska-vira#skupina-758869

6 Muslim Population by Country 2025. (n.d.). World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/muslim-population-by-country

7 SPD. (2015, May 5). Islám do ČR nepatří. SPD – Svoboda a Přímá Demokracie. https://www.spd.cz/islam-do-cr-nepatri/

8 Kostlán, F. (2014, April 23). Hnutí Úsvit Tomia Okamury rozjelo svou předvolební kampaň rasisticky a xenofobně. Romea.cz – Vše o Romech na jednom místě. https://romea.cz/cz/zaostreno/hnuti-usvit-tomia-okamury-rozjelo-svou-predvolebni-kampan-rasisticky-a-xenofobne

9 Ibidem

10 Kern, S. (2017, October 8). The Czech Donald Trump.. Gatestone Institute. https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/11122/andrej-babis-czech-trump

11 Heijmans, P. (2017, November 13). Czech Republic’s tiny Muslim community subject to hate. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/11/13/czech-republics-tiny-muslim-community-subject-to-hate

12 Drozd, V.; Vrabec P. . (2016, August 21). Exkluzivně ze Staroměstského náměstí: Martin Konvička jako salafista na velbloudu. Deník Alarm. https://denikalarm.cz/2016/08/exkluzivni-fotoreport-ze-zadrzeni-martina-konvicky/

13 Bilefsky, D; Richter, J. (2016, August 22). . (2016, August 22). Fake ISIS attack in Prague, Intended as Protest, Causes Panic. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/23/world/europe/prague-fake-isis-attack.html

14 See note [11]

15 ČTK. (2020, January 4). Nešiřte islám v ČR, jinak vás zabijeme, objevilo se na brněnské mešitě. Autora nápisu hledá policie. Lidovky.cz – Lidové noviny. https://www.lidovky.cz/domov/v-brne-nekdo-posprejoval-mesitu-hrozi-zabitim-siritelum-islamu.A200104_123215_ln_domov_ele

16 Endrštová, M. (2015, August 12). Protiislámské spolky rozmístily po Praze figuríny ukamenovaných žen. iDnes.cz. https://www.idnes.cz/praha/zpravy/sochy-ukamenovanych-zen-v-praze.A150812_102441_praha-zpravy_nub

17Právo. (2015, January 17). Zakažme islám jako nacismus, znělo na demonstraci. Právo – daily newspaper.

18 NGP. (2025). The Art of Asia across Space and Time. Národní galerie Praha. https://www.ngprague.cz/en/event/4291/the-art-of-asia-across-space-and-time

19 Ibidem

20 NM. (2025) Sbírka starověkého Předního východu a Afriky. Národní Muzeum. https://www.nm.cz/naprstkovo-muzeum-asijskych-africkych-a-americkych-kultur/sbirkove-oddeleni/sbirka-starovekeho-predniho-vychodu-a-afriky

No Comments