Within minutes of arriving to collect my professionally bound thesis, I found myself on the receiving end of an unsolicited and impenetrable rant about female genital mutilation.

“What’s your paper on?” the shop owner inquired.

“It’s on Muslim women and … ,” I began, but before I could finish my sentence, he had launched into the subject.

The fact that I hadn’t even mentioned the words “female genital mutilation” was irrelevant; merely saying “Muslim women” was a wide enough rabbit hole for him to dart down. My presence as a Muslim woman and my half-delivered topic were the only encouragement he needed.

That he felt authorised to deliver a lecture to me about his understanding of the allegedly sexist treatment of women in Islam, the very subject of my years-long PhD dissertation, didn’t surprise me. This was not the first time a stranger had felt entitled to raise the potential religious interference of my genitals with me.

It’s uncanny how often people try to demonstrate their concern about the alleged oppression of Muslim women by humiliating them. Even finding out the details of my research findings doesn’t seem to deter them from baldly sharing opinions.

When I was neck-deep in my doctoral research, I attended a black-tie journalism-industry dinner on a windy Sydney night. Some of Australia’s most intelligent and perceptive thinkers were in the well-dressed crowd. I had grown accustomed to answering questions about my subject. I had also grown quite used to the standard responses I received to my thesis, and habitually gave ambiguous answers to avoid them.

A well-known and popular journalist approached me and asked what I did for living. His reaction, despite belonging to a group of people usually known for their cognitive skills, was so representative that I scribbled it down on a dinner napkin as soon as he left so I would not forget a word:

Journalist: So what do you do?

Me: I’m completing my PhD.

Journalist: On?

Me: (purposefully vague) Sociology and politics.

Journalist: But what is your exact research question?

Me: (inward sigh at what was inevitably to follow, but valiantly indifferent exterior) I’m investigating the way Muslim women fight sexism within Muslim communities.

Journalist: (with widened, alarmed eyes) That’s dangerous waters!

Me: (through gritted teeth) Not really. It’s been going on for many hundreds of years, and I’ve been spoiled for choice with the number of women who have been willing to be participants in my research.

Journalist: Did they want it known what they were doing? Or did they need it kept secret?

Me: (icy frustration descends into Arctic winter) Oh, many of them were happy to be identified in my research. In fact, some were angry when I suggested giving them a pseudonym, insisting they wanted to be known for this work.

Journalist: (now completely flabbergasted) But … but, did their husbands know of their apostasy?!

Me: (choosing to ignore use of “apostasy” as eyes take on glacial sheen) Actually, many of the women listed their husbands, or another Muslim man – like their father or imam – as their greatest supporters.

Journalist: (now quite literally speechless) …

I’ve had similar exchanges — too many to count — with non-Muslims over the course of my research. Commonplace is the firm conviction that sexism against Muslim women is rife, most often coupled with the utter disbelief that women who challenge sexism could exist, let alone that there are many of them, that they are not a new phenomenon, and that Muslim men often support them in their efforts. I often wonder how people can be so comfortable presenting these attitudes directly to me, a clearly identifiable Muslim woman in a hijab. They do not appear at all uneasy in making it apparent just how bad they think life is for any and all Muslim women, and how unengaged they believe Muslim women to be in confronting the sexism they invariably face.

I have received similar, but different, reactions within some sections of various Muslim communities when they found out the focus of my research. Often I would be purposefully vague when discussing my topic with them, too. I would restrict myself to saying that I was researching “Muslim women”, and avoid highlighting the “fighting sexism” part, as there is a complicated, often suspicious attitude towards anything that may be perceived as “feminism” within Muslim communities. Or I would rush to reassure them that I was not framing this in an anti-religious perspective.

Their scepticism is perhaps an understandable reaction from a minority community that frequently feels under siege, particularly when it comes to women’s rights. I hoped the fact that my research was being carried out from within a common faith, and that it drew explicitly and deeply on the theological resources afforded by this, reassured them that I, unlike many others, was not engaging in an attack on the faith and communities they held dear.

Their scepticism is perhaps an understandable reaction from a minority community that frequently feels under siege, particularly when it comes to women’s rights. I hoped the fact that my research was being carried out from within a common faith, and that it drew explicitly and deeply on the theological resources afforded by this, reassured them that I, unlike many others, was not engaging in an attack on the faith and communities they held dear.

But still certain people within the Muslim community were scornful, rolling their eyes and calling me a feminist — not as a compliment, but a warning. They saw feminism and Islam as inherently at odds.

This is the terrain in which my research into Muslim women occurred. The subject is fraught on multiple fronts; the topic of “Muslim women and sexism” is a minefield of unflappable certainty and indignation from all corners. Yet for something about which so many people are adamantly sure, I feel there is very little information from the women actually involved. It seems to me that, in the argument in which Muslim women are the battlefield, the war rages on and the angry accusations zing past their heads from all sides. The main casualty is, ironically, women’s self-determination.

Islam is arguably the most discussed religion in the west today, in both media and society, and, after terrorism, the plight of Muslim women is probably the most controversial topic of debate. I have been asked, challenged, harangued and abused about “Islam’s treatment of women” countless times in person and online. Nonetheless, there is only a small amount of published work available on the topic of Muslim women fighting sexism within Muslim communities, and much of that focuses on women who see Islam as inherently part of the problem — if not the whole problem — that Muslim women face.

The assumption is that Muslim women need to be extricated from the religion entirely before anything close to liberation or equality can be achieved.

There are limited sociological accounts of Muslim women who fight sexism from a faith-positive perspective, and only a handful of studies that investigate the theological works of some Muslim feminists. The responses to, and motivations of, these women are dealt with coincidentally, as opposed to primarily. This small pool of available resources clashes with what I know anecdotally to be happening in many Muslim communities, as well as the historical accounts of Muslim women who, from the earliest days of Islam, have been challenging the sexism they have experienced by using religious arguments.

For years now I have been speaking about issues relating to Islam, Muslims and gender to the media, both Australian and overseas. In one sense I choose this, but in another it has been chosen for me, moulded by the way others attempt to define and restrict me, more or less obliging me to respond.

It’s a common story. Jasmin Zine, a Canadian scholar, once observed that not just our actions but also our very identities are constantly being shaped by dual, competing discourses that surround us. There’s the fundamentalist, patriarchal narrative, persistently trying to confine the social and public lives of Muslim women in line with the kind of narrow, gendered parameters that are by now so familiar. But there are also some western feminist discourses that seek to define our identities in ways that are quite neocolonial: backward, oppressed, with no hope of liberation other than to emulate whatever western notions of womanhood are on offer. This wedging chimes with my experience, and it’s a problem because, as Zine argues, both arms deny Muslim women the ability — indeed the right — to define our identities for ourselves, and especially to do so within the vast possibilities of Islam.

It is as though male Muslim scholars and non-Muslim western feminists have handed down predetermined scripts for us to live by. And it is left to those people thought not to exist — Muslim women who fight sexism — to rewrite those scenarios and reclaim our identities.

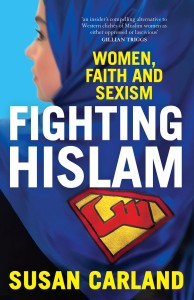

• This is an edited extract from Fighting Hislam: Women, Faith and Sexism by Susan Carland, out now through Melbourne University Press

No Comments