A wave of racism and Islamophobia swept through the municipality of Torre-Pacheco, in Murcia, during July 2025. Although the outbreak of violence lasted no more than a week, it left behind hate crimes, assaults, property damage, vandalism, arson, and the spread of widespread racism. The incidents were claimed as a “hunt for Maghrebis” and were encouraged by influencers and xenophobic groups from other parts of Spain, who spread the message through social media and the press. In Torre-Pacheco, the local response was strong: residents, religious leaders, and institutional representatives rejected the violence and hate speech, affirming civic coexistence [1].

In a city where around 30% of the population is foreign, according to official figures, intercultural coexistence is the norm. A norm driven primarily by necessity, especially due to the lack of labor in fieldwork. Torre-Pacheco is the agricultural capital of the Campo de Cartagena, a very fertile land rich in crops that, since the 1980s, has relied on migrant labor to cover the workforce in the primary sector. What happened in Torre-Pacheco is not an isolated act—not only because various agricultural municipalities have been shaken by racist disturbances on other occasions, but also because it is part of an escalation of structural and systemic hatred, fueled by political discourse and racist narratives.

The field that enriches the region

Fieldwork in Spain is carried out by people willing to accept the physical strain and precarious labor conditions it entails. Many of these workers are migrants. After the hospitality sector, agriculture is the second sector with the highest presence of foreign workers, with 26.6% of employees being foreign-born, most of them of Moroccan origin [2]. EIn the case of Murcia, the percentage rises and approaches 60% [3]. These are the official figures, but the prevalence of the informal economy in this sector should not be overlooked. It is estimated that in agriculture, around 50% of jobs are not formalized with an employment contract [4].

Potato harvest in Cartagena, 2013 © Susana Vera/Reuters.

In Torre-Pacheco, more than 70% of the contracts issued in the municipality are for agricultural work [5]. The agricultural specialization of the Campo de Cartagena region is an example of how the agro-industrial model has shaped the landscape, consolidating certain areas as key players in agricultural production and export. This is the case in Murcia, but also in other parts of the country, such as Almería, Huelva, or Lleida, for example. These regions are essential in the production chain for the national and European markets, generating a significant source of wealth. For instance, in Murcia, lettuce exports generate annual earnings of around €650 million, melon exports €149 million, and celery €77.6 million.

The fields and agriculture of Murcia are heirs to Andalusi and Islamic knowledge.

This economic growth would not be possible without the fundamental work of the people who cultivate and maintain the land and its produce. Yet, this work is the least valued. These are jobs marked by high labor precariousness, instability, and temporariness, with insufficient income—around €5/hour—unpaid hours, lack of labor rights, and, in many cases, a complete absence of legal protection [6].

Members of Vox holding racist banners on July 12, 2025, in Torre-Pacheco © Olmo Blanco/Getty Images.

Against all logic, this July an attempt was made in Torre-Pacheco to promote a “hunt for Maghrebis”—precisely in the same land cultivated by thousands of people of Maghrebi origin, without whom the region’s economic growth would be inconceivable. Migrant populations, or those perceived as such, deserve respect, fair working conditions, and social and labor recognition. Although local residents are aware of this, and the calls for hatred were drowned out by false news and misinformation on the internet, it remains concerning, if not outright incongruous, that people continue to face inequalities based on ethnic, cultural, or religious grounds, alongside institutional and social indifference to racial and religious exclusion, and a human, cultural, and historical disconnect from the environment around us.

The Islamic memory of Murcia

Murcia has a strong Islamic heritage. From the 8th century, it was part of al-Andalus when it was incorporated into the Caliphate of Córdoba; later, it even became its own independent taifa. These centuries of prosperity and regional development were evident in areas such as agriculture, with the introduction of new crops, irrigation methods, and agricultural production techniques. Architecture also bears witness to this Islamic past that endures in the regional capital, including the alcazaba, the city walls, and the mosque of Murcia, which was converted into a Christian temple following the Treaty of Alcaraz and became the origin of the city’s current cathedral. Murcia emerged as a significant center of political, economic, and cultural power, establishing itself as a meeting point for influential figures of the time.

After the Castilian conquest in the 13th century, the majority of the Muslim population continued to practice their faith under Christian rule; they were known as Mudéjars. On the other hand, the Morisco community consisted of those Muslims who were forced to convert to Christianity until the Castilian crown finally expelled them in the 17th century. Prominent authors of the Golden Age, such as Cervantes, Lope de Vega, and Quevedo, along with other literary voices from different periods, genres, and backgrounds, have addressed in their works the significant contributions of the Moriscos to Hispanic society and the tragic consequences of their forced exile.

After the expulsion, the region was left depopulated, and with it, traditional knowledge was lost—such as agricultural techniques, crop cultivation, and water management—creating a deep crisis in terms of productive capacity. Of course, the loss was also social and cultural, with the disappearance of knowledge that was replaced by enforced Christian homogenization. Even so, the Morisco community was so deeply rooted that, despite the severity of the official expulsion, many Moriscos remained in hiding, and many others quietly returned.

All this legacy is systematically marginalized when exclusive or exclusionary narratives are constructed.

The Islamic heritage is still alive in Murcia, visible not only in the architecture of some of its most emblematic monuments but also in the geometric and floral tiles that adorn the cities, in gastronomy and traditional dishes, in street and square names, in urban landscape design, and in the Murcia orchards. However, this entire legacy is systematically marginalized when exclusionary narratives are invented. Its memory is weighed down by structural racism, which strives to render it invisible and to present anything Islamic as foreign, imposed, and even conflictive or problematic.

Archaeological site of San Esteban, Murcia, which preserves remains of the Andalusi suburb of La Arrixaca and part of a possible palace complex (12th century).

Thus, the wave of racism experienced in Torre-Pacheco not only threatens the safety and integrity of Muslim and migrant people, or those perceived as such, but also denies Spain’s rich cultural heritage and history. This distorts our identity as a society and generates injustices and inequalities among those who inhabit the territory and contribute daily to its economic, social, and cultural development. Most alarming is the hatred being incited and encouraged, based solely on stereotypes, falsehoods, and a deliberate intent to harm and sow chaos.

A troubling paradox

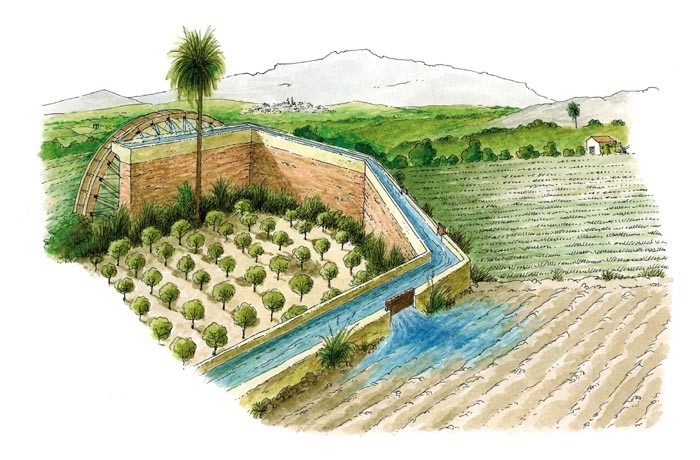

The prevailing violence is not only social but also ecological. It is worth noting that the fields and agriculture of Murcia are heirs to Andalusi and Islamic knowledge. The introduction of crops, agricultural techniques, irrigation systems and hydraulic engineering, landscaping, and cultural and social practices all find their roots in the Islamic period of the Iberian Peninsula. These Andalusi contributions, influences, and traditions have been preserved and maintained, considered essential in the subsequent reconstruction of the Castilian landscape, and have become a key element of the regional identity that endures to this day [7].

Museo de las claras

The water heritage of the Murcia fields was based on a rational and equitable approach to the use of natural resources. However, the current agri-food system, which produces beyond its capacities, depletes resources and pollutes the environment, has replaced sustainability values with productivity. Today, intensive use and poor water management—including dependence on the Tagus-Segura transfer and the pollution of the Mar Menor—are causing severe environmental damage and putting the sustainability of water resources at risk [8]. Greenpeace reports that the Mar Menor is facing a severe ecological crisis due to the overexploitation of aquifers and nitrate pollution from fertilizers used in intensive agriculture [9].

A troubling paradox emerges: we degrade the environment that surrounds and nourishes us while simultaneously precarizing and excluding those who preserve it.

Torre-Pacheco raises awareness about the importance of respect, tolerance, and peaceful coexistence, while also highlighting the profound disconnect people have with the land they inhabit and its historical memory. The coexistence of cultures, religions, and experiences—far from being divisive—is the seed that enriches our society. The Islamic cultural heritage is a clear example, visible in the architectural landscapes that endure in the cities, in the irrigation techniques that have sustained agriculture for centuries, and in other tangible and intangible legacies that continue to shape everyday life today.

Racist and Islamophobic actions impoverish society as a whole, depriving it of dialogue and the many opportunities that diversity brings, while perpetuating an unjustifiable systemic violence that hinders civic coexistence. The paradox of Torre-Pacheco serves as a reminder that places hold history, that cultures intertwine with the land, and that denying diversity is, in essence, denying our very identity.

The poet Hāzim al-Qarṭāyannī (13th century) writes about Murcia and its landscapes:

With so much love, my friend, I loved the garden that was my land, that, far from it, my heart dies.

That land, a haven where the rivers come to rest, is the land of Murcia, the place of my leisure and the dwelling of my joys.

How pleasant it was for me to anchor on your shores!

How much delight I found, and how much peace, among your myrtles!

How I remember the flow of your river, when I gazed upon it from that bank over which the Waḍḍāḥ bridge rises!

All beauty had its place by your waters, between Tabayra and Sabbāḥ.

There, walking back and forth, we traveled seventy miles, among bridges and under the most luxuriant trees.

…

Time was divided according to the seasons, moving from one place to another, like wandering stars in the sky.

Winter was spent in Cartagena, sheltered from the winds by the high mountains, beside the sea.

Summer in the fertile plains of Murcia, under the shade of fruit-laden trees, among alcazars and bridges.

Spring in the fields, meadows, and hills watered by the first rains.

Autumn in the thermal baths, so cherished in eastern Spain.

…

Where the countless norias turn like shields moved in battle by armored warriors, which are the irrigation channels twisted by the wind…

And now our eyes behold gardens surrounded by canals and ponds.

The setting sun gradually disappears, until only the edge of its crown is visible.

But then the glow of Qubbas (the fountain of vats) illuminates our eyes, its light showing us the way.

…

Oh, Murcia, how many sweet and happy people dwell among your myrtles!

And how much tranquility!

How I remember the flow of your river moving away from you; or the Waḍḍāḥ bridge, which I observed from the high bank, upstream! [10]

Julia Martínez Cano y Ainara García Sánchez

Cover photo: Protests on July 14, 2025, in Torre-Pacheco © Olmo Blanco/Getty Images.

REFERENCES

[1] Reina, E. (2025, July 20). Torre Pacheco, the land where the melon devoured the far right. El País. https://elpais.com/espana/2025-07-20/torre-pacheco-la-tierra-donde-el-melon-se-comio-a-la-ultraderecha.html

[2] EFEAGRO. (2025, July 14). The Spanish countryside has 250,000 foreign workers. EFEAGRO. https://efeagro.com/el-campo-espanol-tiene-250-000-afiliados-extranjeros/

[3] González, R. (2025, July 15). Nearly 60% of the workforce in the fields of the Region of Murcia is foreign. Cadena SER. https://cadenaser.com/murcia/2025/07/15/casi-el-60-de-la-mano-de-obra-en-el-campo-de-la-region-de-murcia-son-extranjeros-radio-lorca/

[4] Cáritas (2020). Violations of labor rights in the agricultural sector, hospitality, and domestic work (updated edition 2020). https://www.caritas.es/producto/vulneraciones-de-derechos-laborales-en-el-sector-agricola-la-hosteleria-y-los-empleos-del-hogar/

[5] Statistical Portal of the Region of Murcia (CREM). (2009). Foreign population in Torre-Pacheco. Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia. https://econet.carm.es/web/crem/inicio/-/crem/sicrem/PU_TorrePachecoCifras/P8003/sec6.html

[6] Briones-Vozmediano, E., & González-González, A. (2022). Exploitation and socio-labor precariousness: the reality of migrant workers in agriculture in Spain. Archivos de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales, 25(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.12961/aprl.2022.25.01.022

[7] Martínez Martínez, M. (2017). The identity of the landscape: the Andalusi and Castilian orchards of Murcia in the 13th century. Historia. Instituciones. Documentos, 44, 212–241. https://doi.org/10.12795/HID.2017.I44.09

[8] González, A. (2025, July 1). Ecologistas en Acción identifies eight water-related conflicts in the Region, including the transfer and the Mar Menor. Cadena SER. https://cadenaser.com/murcia/2025/07/01/ecologistas-en-accion-identifica-ocho-conflictos-planteados-por-el-agua-en-la-region-entre-ellos-el-trasvase-y-el-mar-menor-radio-murcia/

[9] Greenpeace Spain. (2022). Mar Menor, hostage of the aquifer that polluted the irrigation system. Greenpeace Spain. https://es.greenpeace.org/es/en-profundidad/sos-acuiferos/mar-menor/

[10] Martínez, M. (2015). Andalusi Murcia (711–1243): Daily life. Suomalaisen Tiedeakatemian Toimituksia. Annales Academiæ Scientiarum Fennicæ, Humaniora (Vol. 373). Academia Scientiarum Fennica. https://medievalistas.es/wp-content/uploads/attachments/01169.pdf

No Comments