The Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the all-out war throughout the country, has been the focus of political and media attention for several weeks. The gravity of the humanitarian situation certainly justifies this coverage, and allows us to remember that all wars are reprehensible. (Cover photo: Alisdare Hickson).

However, this is precisely the point that leaves a bitter taste in the mouth, because if all violations of fundamental rights and freedoms are to be condemned and all lives are equal, how can we explain the double standards that have been installed in the discursive sphere since the beginning of the conflict? And likewise, why do the victims of this conflict seem to enjoy a solidarity that is not received, for example, by Syrians, Yemenis, Afghans, Sudanese…?

This article does not intend to answer these questions in their complex and diverse totality, but to underline some important points to remind us that the values of humanity and solidarity, invoked at every turn in recent days, seemed to have disappeared until now, and if its return can be positive it must be done in a universal way and not fall into discriminatory, racist and Islamophobic discourses and practices.

The importance of the asylum principle: looking at the past to understand the present

First of all, it is important to remember that the decision to flee a situation of war or horror is guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Articles 13 and 14:

“1. Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state. 2. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.” Article 13

“1. Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

- This right may not be invoked in the case of prosecutions genuinely arising from non-political crimes or from acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.” Article 14

The freedom of movement recognized by the 1948 text is therefore one of the fundamental rights of all persons, without discrimination. It is also the cornerstone of one of the rights at the heart of current events: the right to asylum.

The question of asylum is rooted in the history of mankind, and its ancient origins remind us of its importance. Some historians trace the idea and notion of asylum back to ancient Egypt, specifically to the Treaty of Qadesh (1280 B.C.) between Ramses II and Hattusili III, which for the first time in history addressed, in transcribed form, the issue of “refugees” by containing several clauses concerning the protection and repatriation of prisoners from the rival camp.

However, it was in the time of ancient Greece that the concept of asylum acquired greater importance, especially when it obtained its first definition. From the 5th century BC onwards, Greek jurists and thinkers began to explain that there were sacred places, “άσυλον asylon“, which were therefore inviolable and could not be plundered. These places could also serve as a refuge for anyone fleeing from human justice.

Throughout history, this notion of asylum has acquired different meanings and applications, depending on the time and place, but the principles on which it has been based have always been the same, those of hospitality and protection. Its evolution and definition was closely linked to religions, from Antiquity to the Middle Ages.

Such is the case of the three major monotheistic religions, whose founding stories remind us of this notion of asylum: 1. a situation of danger (persecution), 2. a fleeing (exile) and 3. the search for a place of protection (asylum). For Judaism this sequence of events is called the Exodus, for Christianity the flight of the Holy Family to Egypt and for Islam the Hegira.

These religions have given rise to different normative systems dealing with the phenomenon of displacement, based on ethical and moral values based on the need for welcome and hospitality. This is the case of Islam and the Shari’a, which, due to their history, have developed rules and laws concerning the treatment of foreigners and people who have been forced to take the path of exile, also recognizing the value of those who come to the aid of people fleeing violence, as was the case of the Prophet Muhammad in Medina.

Between the principle and the application, an unbridgeable gap, or almost…

However, the concept of asylum, as we understand it today, is more recent and is linked to the construction of nation states from the 19th century onwards and, above all, to the two world wars and the development of international law.

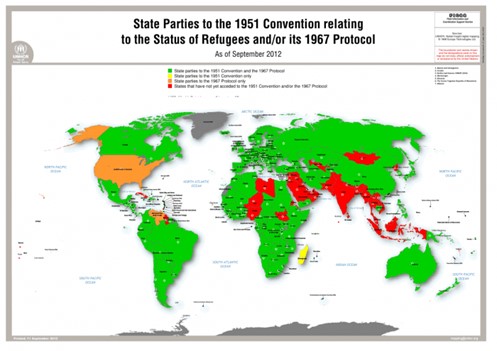

The Geneva Convention on Refugees (1951) and the New York Protocol (1967) are the founding texts which, taking up the ideas of protection and hospitality inherent in the right of asylum, defined the notion of “refugee” and established the fundamental rights to be guaranteed to this group. These texts are based on the principle of non-discrimination and non-refoulement and have been ratified by 145 States.

The principle of asylum, and refugee status, has thus become an internationally recognized right, but also, unfortunately, an object of politics and geopolitics. This politicization of asylum has given rise to a gap between the principle enunciated in the texts and its actual application, which has grown steadily over the years. This fundamental right has thus become in most cases an illusion rather than a reality.

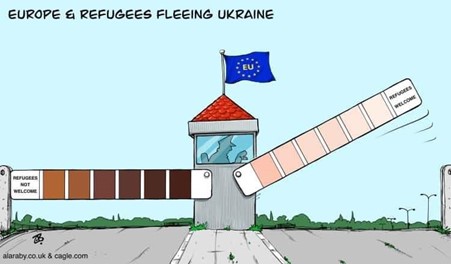

However, it seems that since the war in Ukraine, a bridge is being built over this abyss that once seemed insurmountable. The question is, nevertheless, if these efforts and this bridge are intended to make this long-forgotten right a reality for all those who need it. Unfortunately, the negative answer is not surprising, as there seem to be barriers restricting its access and crossing.

You don’t have to look far to realize that many people continue to risk their lives trying to cross borders in the face of Western indifference, as two babies and three women died and more than 40 people went missing in the Mediterranean on March 12.

However, this tragic news does not arouse the emotion and indignation of public opinion, or does so on a much smaller scale than what we have experienced in recent weeks with the Ukrainian refugees. This is especially the case with the media, which also play an important agenda-setting role.

What is behind this double standard? Racism, Eurocentrism, Islamophobia…

Indeed, the European public sphere has been trying for years to normalize or dehumanize the death of thousands of people at our borders through a process of alterization or otherness that turns them into “Others”. In this context, images and information about the war in Ukraine and refugees are different, and aim to link these people to an “Us”. This self-recognition in their situation seeks to evoke empathy and indignation about the conflict they are experiencing. The result is an unequal treatment of the victims of the different conflicts according to geographical, ethnic, religious criteria…In this vision, otherness, real or imaginary, becomes a factor of dehumanization.

This phenomenon is justified by a rhetoric that, despite a pseudo-justification of an urgent need for international protection, is in reality based on racist and islamophobic politics and thinking. The latter seeks to make a supposed “cultural proximity” the determining factor of empathy, or, to use the term developed by Judith Butler, of “grievability“, that is to say, of the capacity to mourn a life, or to consider whether they are worthy of living and therefore of grieving.

This variable geometry of empathy can be explained in many ways, and Butler has developed an important bibliography around it. Notable in this regard is her latest book written with French philosopher Frédéric Worms, Le vivable et l’invivable.

One of the main ideas of her years of study, reflected in this book, is that the ability to live one’s own life is socially discriminated against and unequally valued according to sociopolitical norms. So is the empathy that arises from a person’s suffering and its capacity to move consciences and help in the face of the unlivable.

One of the main ideas of her years of study, reflected in this book, is that the ability to live one’s own life is socially discriminated against and unequally valued according to sociopolitical norms. So is the empathy that arises from a person’s suffering and its capacity to move consciences and help in the face of the unlivable.

Worms explains that “if we can die, in the classical sense of the word, of hunger or cold, our life can be made unbearable by the lack of recognition, by depression or melancholy…” . This is precisely what we want to denounce, that this necessary recognition is granted to some groups of people, but not to others, and that this arbitrary choice is, in part, the result of systemic racism.

The images and atrocities committed by the regime of Bashar al Assad and Putin in Syria escapes no one, so it might seem logical that they should be protected and considered – like Ukrainians – refugees. However, the reality and discourse are totally different, and they are still mainly described and perceived as “Muslim migrants“.

The spokesmen of this hypocrisy justify this double standard with the argument of an alleged “cultural proximity”. However, this myth deserves to be deconstructed to show its true face: that of a culturalist, essentialist, not to say racist and Islamophobic thinking, which denies the humanity of hundreds of thousands of people.

This narrative has aberrant discriminatory results, such as the attempt to distinguish between “good” and “bad” refugees, i.e., “civilized” and “savages.” This racism, coming from a colonial rhetoric of “pseudo-civilization”, is pervasive in the discursive field, as these few examples show:

- Daniel Hannan, of The Telegraph wrote: “They seem so like us. That is what makes it so shocking. War is no longer something visited upon impoverished and remote populations. It can happen to anyone.”

- On February 26, CBS News correspondent Charlie D’Agata said: “But this isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is a relatively civilized, relatively European — I have to choose those words carefully, too — city, one where you wouldn’t expect that, or hope that it’s going to happen.”

- “We’re not talking here about Syrians fleeing the bombing of the Syrian regime backed by Putin, we’re talking about Europeans leaving in cars that look like ours to save their lives.” Philippe Corbé on the French channel BFM TV.

“Civilized”

pic.twitter.com/AiU7uVmjMr— Imraan Siddiqi (@imraansiddiqi) February 26, 2022

This situation is nothing more than the symbol of the normalization of a discursive and symbolic field that seeks to legitimize the ideas of S. Huntington of a “clash of civilizations” or of a “great substitution” spread by R. Camus.

The leader of Vox, Santiago Abascal, explained in the framework of this ideology before the Congress that: “everyone can understand the difference between these flows [from Ukraine] and the invasions of young people of Muslim origin of fighting age who have thrown themselves against the borders of Europe”.

What is perhaps more serious is that this Islamophobic and racist discourse, criticized by the opposition, is nothing more than a reflection of the policy of the vast majority of European governments, regardless of the party to which they belong.

Indeed, how not to speak of differentiated state racism, and a certain “European privilege”, when the authorities decided to set up a system to grant papers within 24 hours to Ukrainian refugees, while, as Syrian journalist Okba Mohammad explains in elDiario.es, his application took two years and five months to be accepted. Despite the fact that he too was fleeing a war and the barbarities perpetrated by Russia.

The importance of language and vocabulary: Ukrainian “refugees” versus “migrants”

It is enough to look at the language to understand this hypocrisy. It is no longer a question of “protecting ourselves from irregular migratory flows“, as Emmanuel Macron announced less than a year ago after the Taliban seizure of Kabul, but, on the contrary, of doing everything possible to welcome Ukrainian “refugees” in the best conditions.

Thus, we observe how vocabulary changes according to political interests. One of the consequences is the decontextualization of conflicts. In other words, some are normalized or justified by the supposedly “uncivilized” character of the country or region. Likewise, people fleeing these wars are directly excluded from the restricted club of refugees and their fundamental rights, such as the right to asylum, are violated. Thus, hospitality, an essential principle, is not respected and international law is breached.

Research published in 2016 and conducted in 15 European countries, entitled: “How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers” showed that “voters favor applicants who will contribute to the recipient country’s economy, who have suffered severe physical or mental distress rather than economic hardship, and who are Christian rather than Muslim. These preferences are similar across countries and independent of the voters’ personal characteristics.”

Mobilize and deconstruct our prejudices to fight against these discourses

In light of this media coverage and political response, one of the first entities to issue a statement critical of the situation was the Arab and Middle Eastern Journalists Association (AMEJA), which called on all news organizations to beware “of implicit and explicit bias in their coverage of war in Ukraine,” adding that they “condemns and categorically rejects orientalist and racist implications that any population or country is “uncivilized” or bears economic factors that make it worthy of conflict. This type of commentary reflects the pervasive mentality in Western journalism of normalizing tragedy in parts of the world such as the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. It dehumanizes and renders their experience with war as somehow normal and expected.”

It is not a question of diverting attention from the Ukrainian drama, but, on the contrary, of deconstructing the prejudices that make it a unique conflict or different from others. Even if journalistic objectivity is, of course, a myth, nothing prevents us from wanting to move towards a regulation of the informative and visual field in which informative prejudices cease to be Eurocentric.

This is even more important if we take into account the influence of the media on public opinion and their impact on the political agenda, which contributes to the structural dimension of these discriminations. Thus, places of refuge for Ukrainian refugees are quickly found, while until now, the most common discourse was about the lack of capacity of states to provide housing for refugees and their inability to accommodate all the misery of the world.

In conclusion, we can say that, faced with this situation, the feeling is that of an intense internal struggle between a sincere joy for the people who are fleeing terror and benefiting from a real surge of solidarity; and a deep sadness mixed with a growing indignation to see that the color of one’s skin or one’s (supposed) religious affiliation continue to be grounds for exclusion, as shown by the inhuman images of discrimination and racism at the Polish border… Let’s hope that this limited solidarity can be transformed in the future into a true humanism.

Tristan Semiond – FUNCI

No Comments